TurbuStat¶

TurbuStat implements a 14 turbulence-based statistics described in the astronomical literature. TurbuStat also defines a distance metrics for each statistic to quantitatively compare spectral-line data cubes, as well as column density, integrated intensity, or other moment maps.

The source code is hosted here. Contributions to the code base are very much welcome! If you find any issues in the package, please make an issue on github or contact the developers at the email on this page. Thank you!

To be notified of future releases and updates to TurbuStat, please join the mailing list: https://groups.google.com/forum/#!forum/turbustat

If you make use of this package in a publication, please cite our accompanying paper:

@ARTICLE{Koch2019AJ....158....1K,

author = {{Koch}, Eric W. and {Rosolowsky}, Erik W. and {Boyden}, Ryan D. and

{Burkhart}, Blakesley and {Ginsburg}, Adam and {Loeppky}, Jason L. and

{Offner}, Stella S.~R.},

title = "{TURBUSTAT: Turbulence Statistics in Python}",

journal = {\aj},

keywords = {methods: data analysis, methods: statistical, turbulence, Astrophysics - Instrumentation and Methods for Astrophysics},

year = "2019",

month = "Jul",

volume = {158},

number = {1},

eid = {1},

pages = {1},

doi = {10.3847/1538-3881/ab1cc0},

eprint = {1904.10484},

adsurl = {https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2019AJ....158....1K},

adsnote = {Provided by the SAO/NASA Astrophysics Data System}

}

If your work makes use of the distance metrics, please cite the following:

@ARTICLE{Koch2017,

author = {{Koch}, E.~W. and {Ward}, C.~G. and {Offner}, S. and {Loeppky}, J.~L. and {Rosolowsky}, E.~W.},

title = "{Identifying tools for comparing simulations and observations of spectral-line data cubes}",

journal = {\mnras},

archivePrefix = "arXiv",

eprint = {1707.05415},

keywords = {methods: statistical, ISM: clouds, radio lines: ISM},

year = 2017,

month = oct,

volume = 471,

pages = {1506-1530},

doi = {10.1093/mnras/stx1671},

adsurl = {http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2017MNRAS.471.1506K},

adsnote = {Provided by the SAO/NASA Astrophysics Data System}

}

Citations courtesy of ADS

Papers using TurbuStat¶

TurbuStat Developers¶

- Eric Koch

- Erik Rosolowsky

- Ryan Boyden

- Blakesley Burkhart

- Adam Ginsburg

- Jason Loeppky

- Stella Offner

- Caleb Ward

Many thanks to everyone who has reported bugs and given feedback on TurbuStat!

- Dario Colombo

- Jesse Feddersen

- Simon Glover

- Jonathan Henshaw

- Sac Medina

- Andrés Izquierdo

Contents:

Installing TurbuStat¶

The newest release of TurbuStat is available on pip:

>>> pip install turbustat

TurbuStat can also be installed from the github repository.

TurbuStat requires the follow packages:

- astropy>=2.0

- numpy>=1.7

- matplotlib>=1.2

- scipy>=0.12

- sklearn>=0.13.0

- statsmodels>=0.4.0

- scikit-image>=0.12

The following packages are optional when installing TurbuStat and are required only for specific functions in TurbuStat:

- spectral-cube (>v0.4.4) - Efficient handling of PPV cubes. Required for calculating moment arrays in

turbustat.data_reduction.Moments.- radio_beam - A class for handling radio beams and useful utilities. Required for correcting for the beam shape in spatial power spectra. Automatically installed with spectral-cube.

- astrodendro-development - Required for calculating dendrograms in

turbustat.statistics.dendrograms- emcee - MCMC fitting in

PCAand- pyfftw - Wrapper for the FFTW libraries. Allows FFTs to be run in parallel.

- To install TurbuStat, clone the repository::

- Change into the TurbuStat directory and run the following to install TurbuStat::

>>> python setup.py install # doctest: +SKIP

If you find any issues in the installation, please make an issue on github or contact the developers at the email on this page. Thank you!

- To run the testing suite::

>>> MPLBACKEND='agg' python setup.py test # doctest: +SKIP

The matplotlib backend needs to be set to avoid having interactive plots pop up during the tests.

Accepted Data Types¶

The TurbuStat routines can accept several different data types.

FITS HDU¶

The most common format is a FITS HDU. These can be loaded in python with the fits library:

>>> from astropy.io import fits

>>> hdulist = fits.open("test.fits")

>>> hdu = hdulist[0]

The TurbuStat statistics expect a single extension for a FITS file to be given.

Numpy array and header¶

The data can be given as a numpy array, along with a FITS header. This may be useful for data generated from simple physical models (see preparing simulated data). The data can be given as a 2-element tuple or list:

>>> input_data = (array, header)

>>> input_data = [array, header]

Spectral-Cube objects¶

The spectral-cube package is a dependency of TurbuStat for calculating moment arrays and spectrally regridding cubes for the VCA statistic. When the data need to be preprocessed, it will often be easiest to work with a SpectralCube object. See the spectral-cube tutorial for more information:

>>> from spectral_cube import SpectralCube

>>> cube = SpectralCube("test.fits")

This SpectralCube object can be sliced or used to create moment maps. These spatial 2D maps are called a “Projection” or “Slice” and both are accepted by the TurbuStat statistics:

>>> sliced_img = cube[100]

>>> moment_img = cube.moment0()

The Projection object also offers a number of convenient functions available for a SpectralCube, making it easy to manipulate and alter the data as needed. To load a spatial FITS image as a projection:

>>> from spectral_cube import Projection

>>> img_hdu = fits.open("test_spatial.fits")[0]

>>> proj = Projection.from_hdu(img_hdu)

Preparing Simulated Data¶

TurbuStat requires the input data be in a valid FITS format. Since simulated observations do not always include a valid observational FITS header, we provide a few convenience functions to create a valid format.

We start with a numpy array of data from some source. First consider a spectral-line data cube with 2 spatial dimensions and one spectral dimension (also called a PPV cube; position-position-velocity). We will need to specify several quantities, like the angular pixel scale, to create the header:

>>> import numpy as np

>>> import astropy.units as u

>>> from turbustat.io.sim_tools import create_fits_hdu

>>> cube = np.ones((8, 16, 16))

>>> pixel_scale = 0.001 * u.deg

>>> spec_pixel_scale = 1000. * u.m / u.s

>>> beamfwhm = 0.003 * u.deg

>>> imshape = cube.shape

>>> restfreq = 1.4 * u.GHz

>>> bunit = u.K

>>> cube_hdu = create_fits_hdu(cube, pixel_scale, spec_pixel_scale, beamfwhm, imshape, restfreq, bunit)

cube_hdu can now be passed to the TurbuStat statistics, or loaded into a spectral_cube.SpectralCube with SpectralCube.read(cube_hdu) for easy manipulation of the PPV cube.

For a two-dimensional image, the FITS HDU can be made in almost the same way, minus spec_pixel_scale:

>>> img = np.ones((16, 16))

>>> imshape = img.shape

>>> img_hdu = create_fits_hdu(img, pixel_scale, beamfwhm, imshape, restfreq, bunit)

The FITS HDU can be given to TurbuStat statistics, or converted to a spectral_cube.Projection with Projection.from_hdu(img_hdu).

You can also create just the FITS headers with:

>>> from turbustat.io.sim_tools import create_image_header, create_cube_header

>>> img_hdr = create_image_header(pixel_scale, beamfwhm, img.shape, restfreq, bunit)

>>> cube_hdr = create_cube_header(pixel_scale, spec_pixel_scale, beamfwhm, cube.shape, restfreq, bunit)

Units¶

The units should be an equivalent observational unit, depending on the required data product (PPV cube, zeroth moment, centroid, etc…). While TurbuStat does not explicitly check for the input data units, two things should be kept in mind:

- The data cannot be log-scaled.

- When comparing data sets, both should have the same unit. Most statistics are not based on the absolute scale in the data, but it is best to avoid possible misinterpretation of the results.

Noise and missing data¶

To create realistic data, noise could be added to img and cube in the above examples. The simplest form of noise is Gaussian and can be added to the data with:

>>> sigma = 0.1

>>> noisy_cube = cube + np.random.normal(0., sigma, size=cube.shape)

In this example, Gaussian noise with standard deviation of 0.1 and mean of 0. is added to the cube.

A common observational practice is to mask noise-only regions of an image or data cube. A simple example is, with knowledge of the standard deviation of the noise, to impose an \(N-\sigma\) cut to the data:

>>> N = 3.

>>> # Create a boolean array, where True is above the noise threshold.

>>> signal_mask = noisy_cube > N * sigma

>>> # Set all places below the noise threshold to NaN in the cube

>>> masked_cube = signal_mask.copy()

>>> masked_cube[~signal_mask] = np.NaN

TurbuStat does not contain routines to create robust signal masks. Examples of creating signal masks can be found in Rosolowsky & Leroy 2006 and Dame 2011.

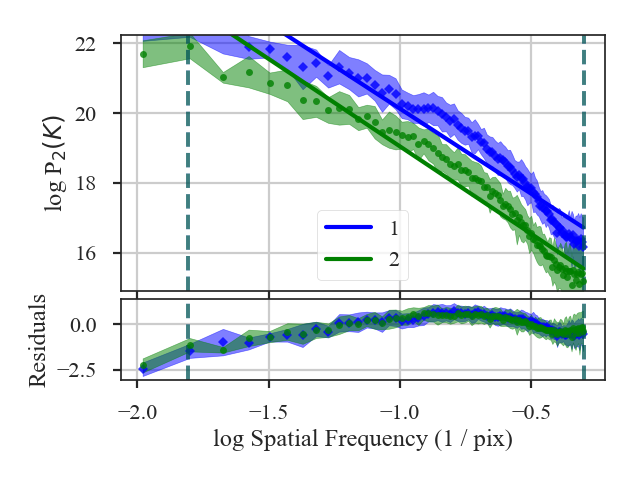

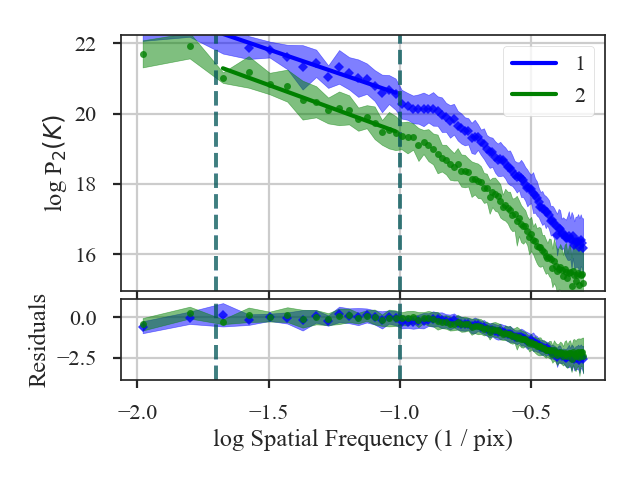

Excluding the dissipation range¶

When using synthetic observations from simulations, care should be taken to only fit scales in the inertial range. The power-spectrum tutorial shows an example of limiting the fit to the inertial range. The power-spectrum in the dissipation range in that example steepens significantly and is not representative of the turbulent index. This warning should be heeded for power-spectrum-based methods, like the spatial power-spectrum, MVC, VCA and VCS. Spatial structure functions, like the wavelet transform and the delta-variance should also be examined closely for the inflence of the dissipation range on small scales.

Source Code¶

turbustat.io.sim_tools Module¶

Functions¶

create_cube_header(pixel_scale, …[, v0]) |

Create a basic FITS header for a PPV cube. |

create_fits_hdu(data, *header_args) |

Return a FITS hdu for a numpy array of data. |

create_image_header(pixel_scale, beamfwhm, …) |

Create a basic FITS header for an image. |

Data Requirements¶

Use of the statistics and distance metrics require the input data to satisfy some criteria.

Spatial Projection¶

TurbuStat assumes that the spatial dimensions of the data are square on the sky. All physical and angular dimensions will be incorrect, otherwise. Data with non-square pixels should first be reprojected. This can be easily done using spectral-cube:

>>> reproj_cube = cube.reproject(new_header) # doctest: +SKIP

>>> reproj_proj = proj_2D.reproject(new_header_2D) # doctest: +SKIP

Considerations for distance metrics¶

The correct pre-processing of data sets is crucial for attaining a meaningful comparison. Listed here are pre-processing considerations that should be considered when using the distance metrics.

The extent of these effects will differ for different data sets. We recommend testing a subset of the data by placing the data at a common resolution (physical or angular) and grid-size, depending on your application. Smoothing and reprojection operations are straightforward to perform with the spectral-cube package.

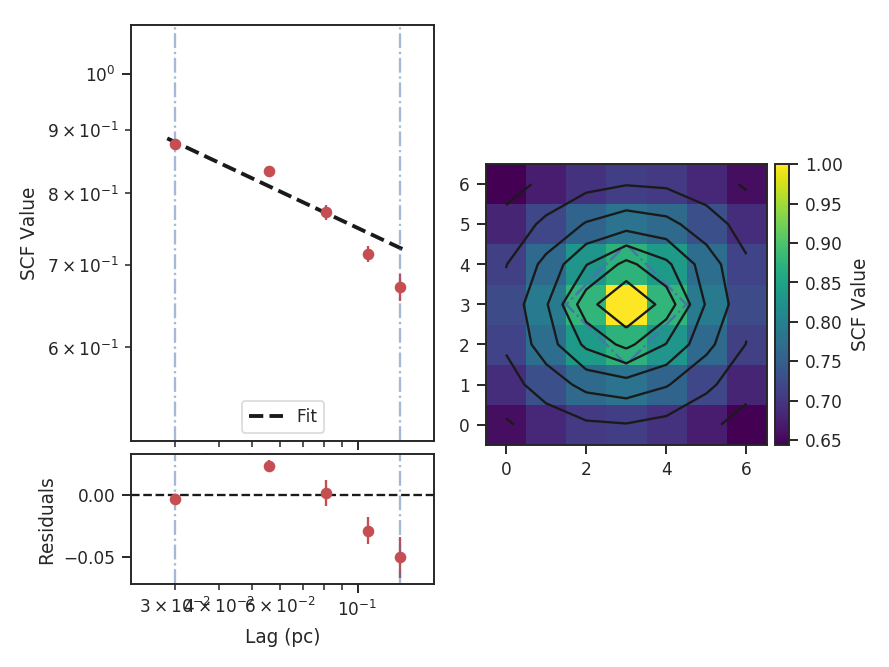

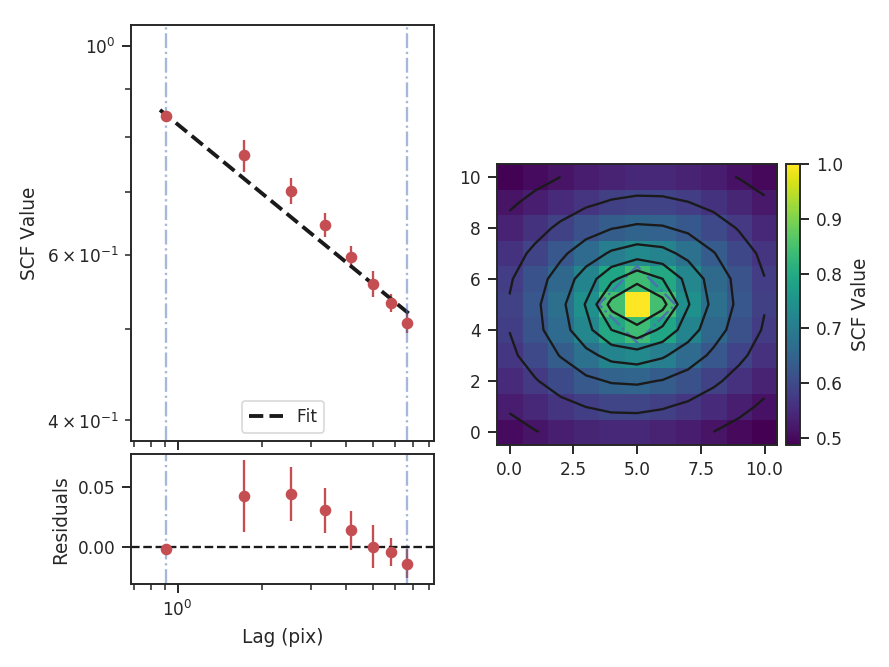

Spatial scales – Unlike many of the statistics, the distance metrics do not consider physical spatial units. Specifically, metrics that directly compare values at specific scales (

DeltaVariance_Distance,SCF_Distance) will use the given WCS information for the data sets to find a common angular scale.Different spatial sizes are less of a concern for slope-based comparisons, but discrepancies can arise if the data sets have different noise levels. In these cases, the scales used to fit to the power-spectrum (or the equivalent statistic output) should be chosen carefully to avoid bias from the noise. A similar issue can arise when comparing different simulated data sets if the simulations have different inertial ranges.

Spectral scales – The spectral sampling and range should be considered for all methods that utilize the entire PPV cube (SCF, VCA, VCS, dendrograms, PCA, PDF). The issue with using different-sized spectral pixels affects the noise properties, and in some statistics, the measurement itself.

For the former, the noise level can introduce a bias in the measured quantities. To mitigate this, data can be masked prior to running metrics. Otherwise, minimum cut-off values can be specified for metrics that utilize the actual intensity values of the data, such as dendrograms and the PDF. For statistics that are independent of intensity, like a power-law slope or correlation, the fitting range can be specified for each statistic to minimize bias from noise. This is the same effect described above for spatial scales.

For the second case, the VCA index is expected to change with spectral resolution depending on the underlying properties of the turbulent fields (see the VCA tutorial).

Data units for distance metrics¶

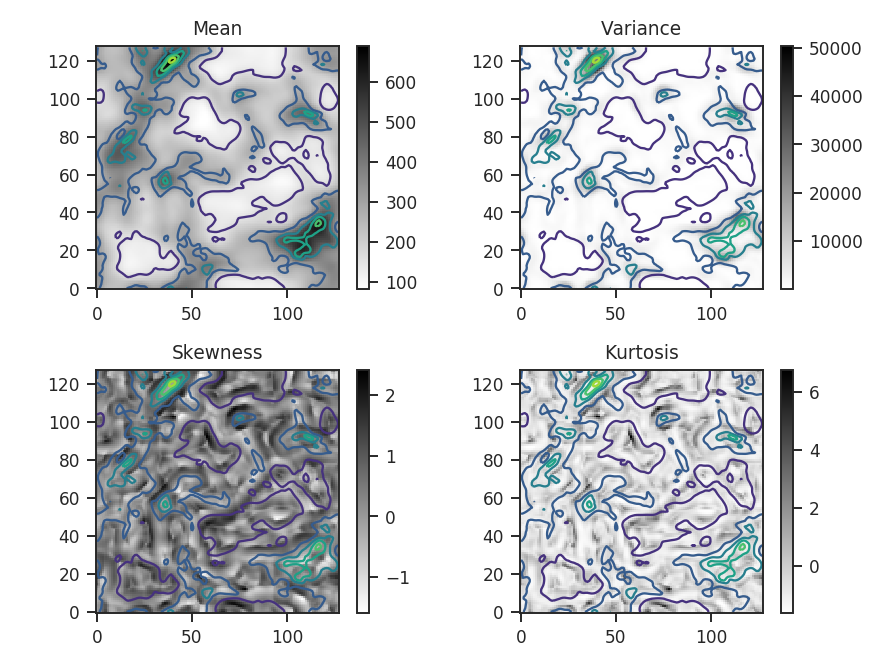

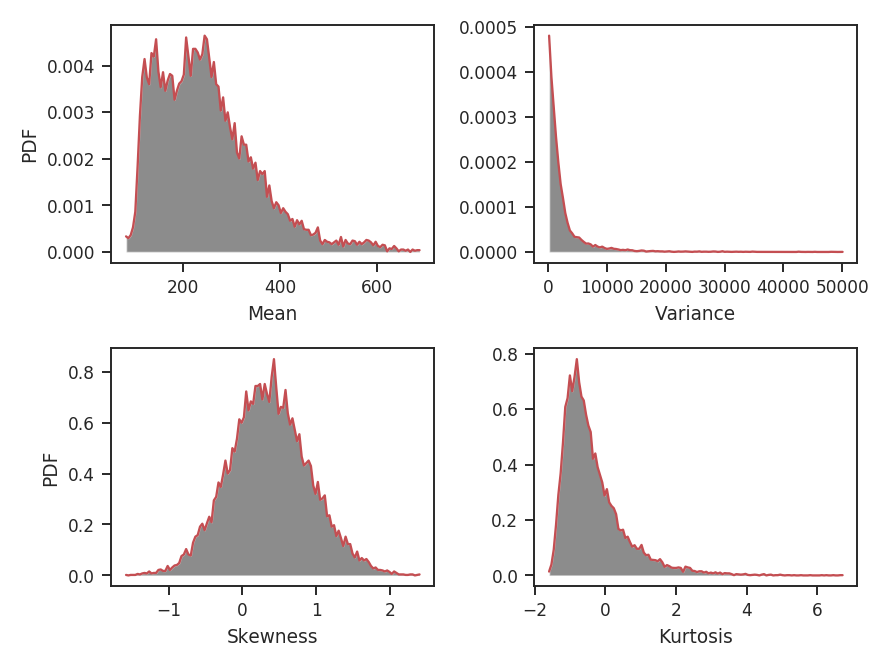

Most of the distance metrics will not depend on the absolute value of the data sets. The exceptions are when values of a statistic are directly compared. This includes Cramer_Distance, the curve distance in DeltaVariance_Distance, and the bins used in the histograms of StatMoments_Distance and PDF_Distance. While each of these methods applies some normalization scheme to the data, we advise converting both data sets to a common unit to minimize possible discrepancies.

Deriving Cube Moments¶

The Moments class returns moment arrays as well as their errors for use with 2D statistics in the package. Moments are derived using spectral-cube. Definitions for the moments are also available in the spectral-cube documentation.

Basic Use¶

Moments are easily returned in the expected form for the statistics with Moments. This class takes a FITS file of a spectral-line cube as input and creates moment arrays (zeroth, first, and line width) with their respective uncertainties.:

>>> from turbustat.moments import Moments

>>> # Load in the cube "test.fits"

>>> mm = Moments("test.fits")

>>> mm.make_moments()

>>> mm.make_moment_errors()

>>> output_dict = mm.to_dict()

output_dict is a dictionary that contains keys for the cube and moments. The moment keys contain a list of the moment and its error map.

The moments can also be saved to FITS files. The to_fits function saves FITS files of each moment. The input to the function is the prefix to use in the filenames:

>>> mm.to_fits("test")

This will produce three FITS files: test_moment0.fits, test_centroid.fits, test_linewidth.fits for the zeroth, first, and square-root of the second moments, respectively. These FITS files will contain two extensions, the first with the moment map and the second with the uncertainty map for that moment.

TurbuStat Tutorials¶

Tutorials are provided for each of the statistic classes and their associated distance metric classes. The tutorials use the same two data sets, described on the data for tutorials page.

The plotting routines are highlighted in each of the tutorials. For users who require custom plotting routines, we recommend looking at the plotting source code as a starting point.

Data for tutorials¶

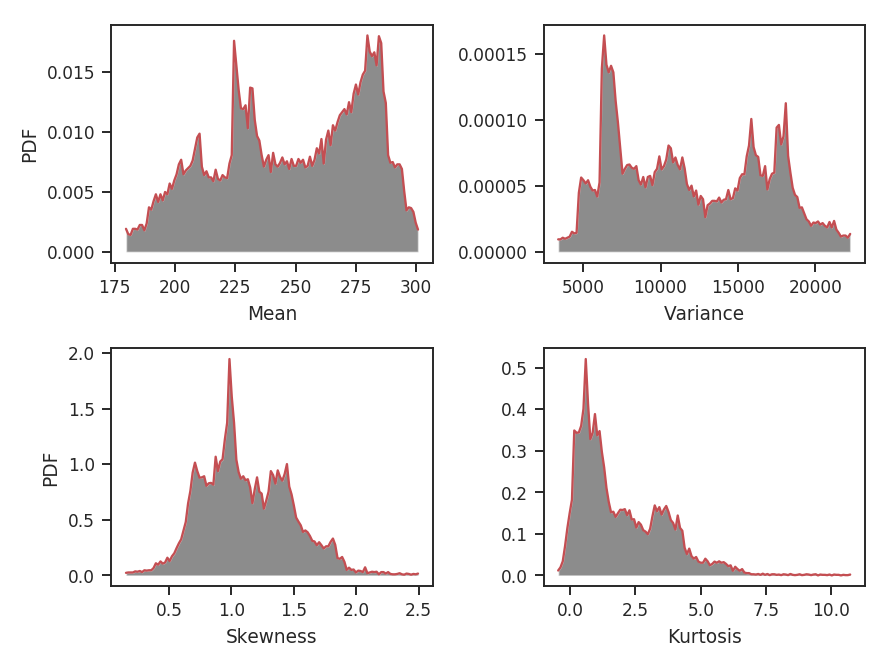

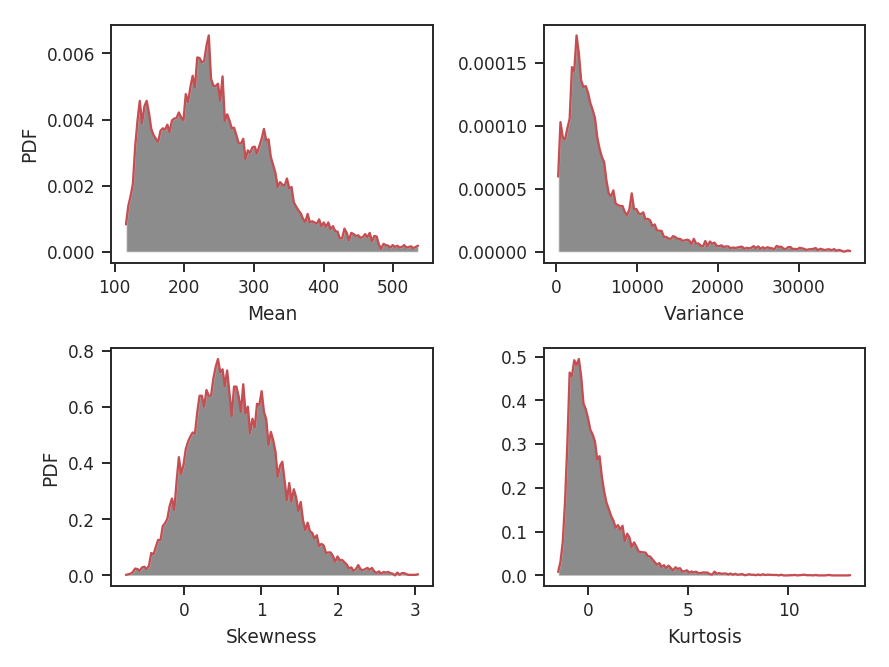

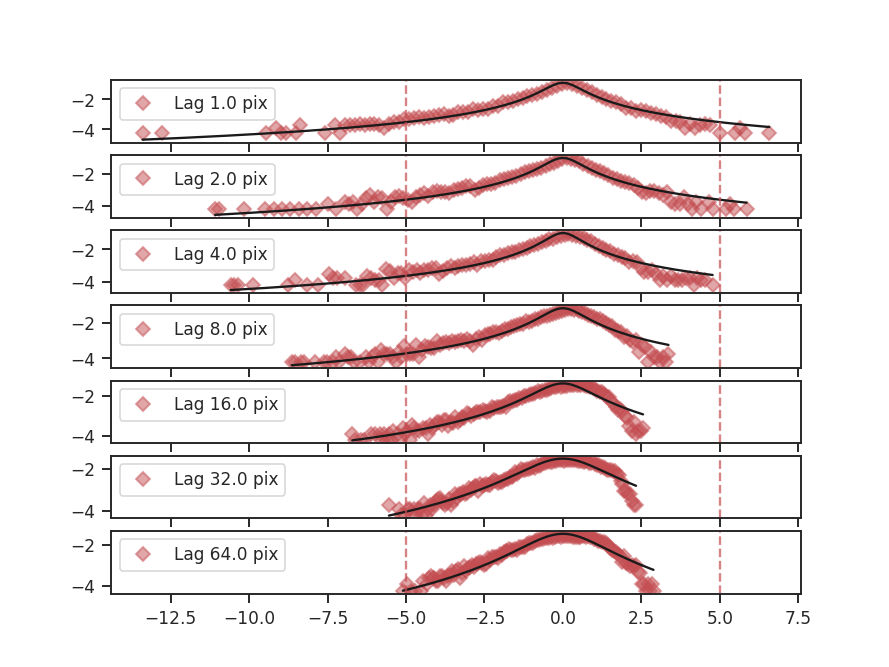

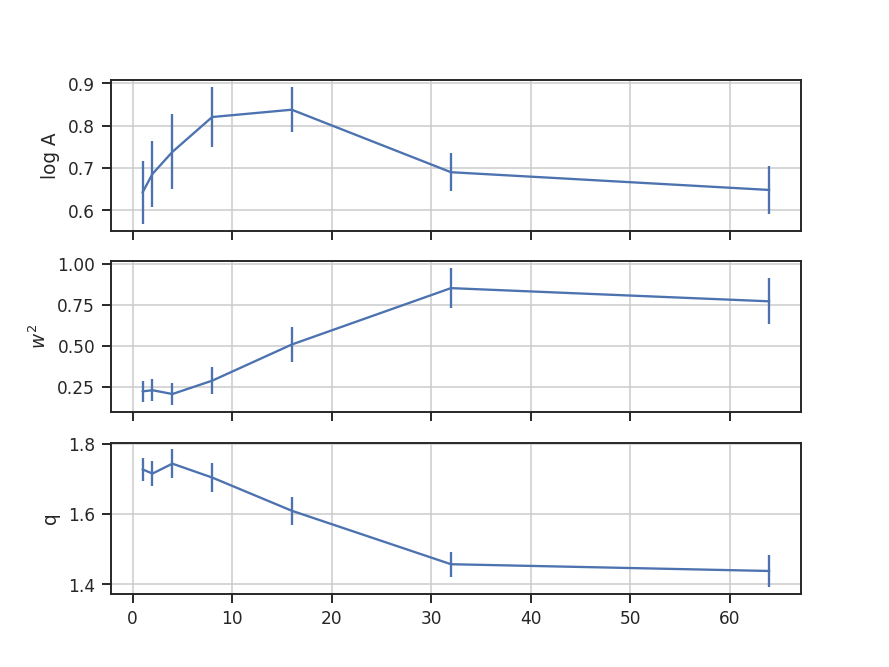

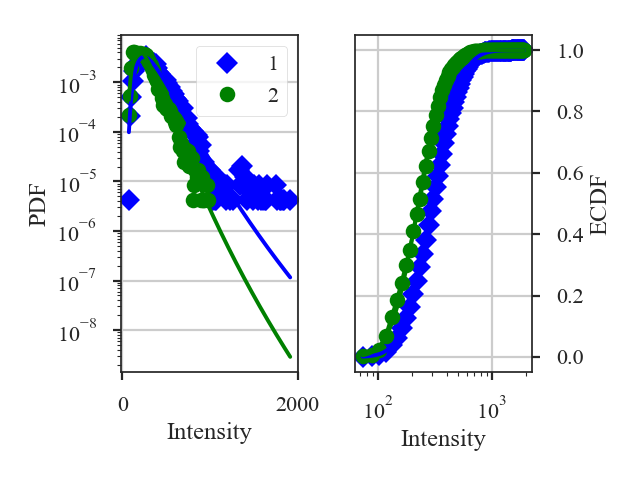

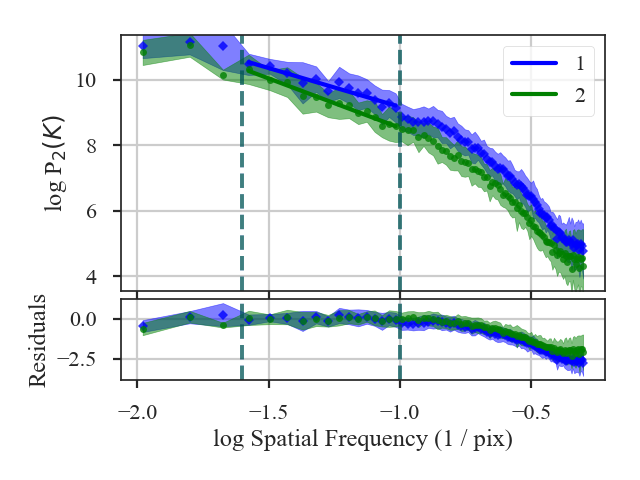

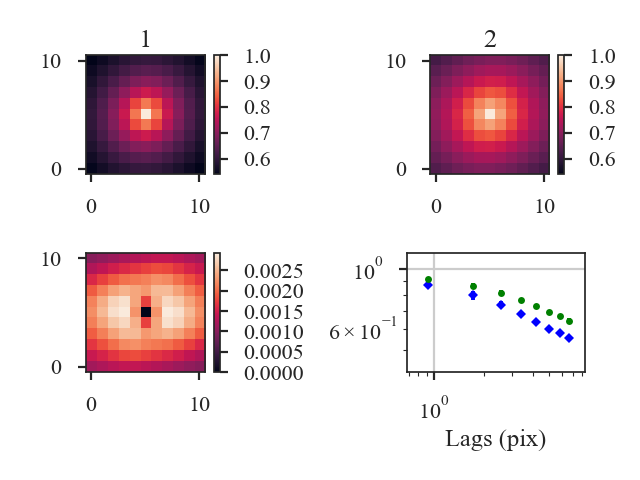

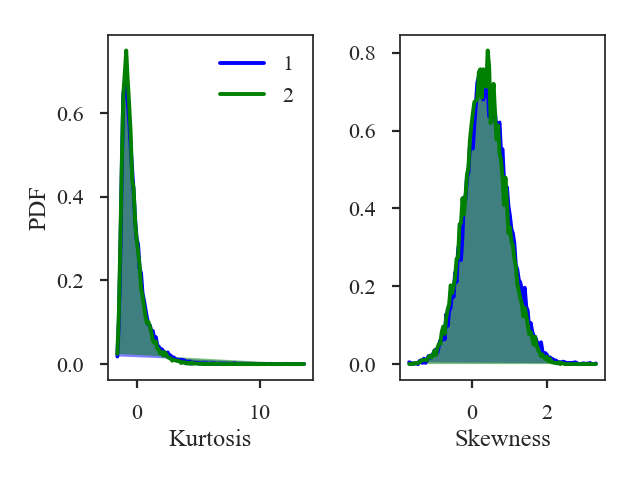

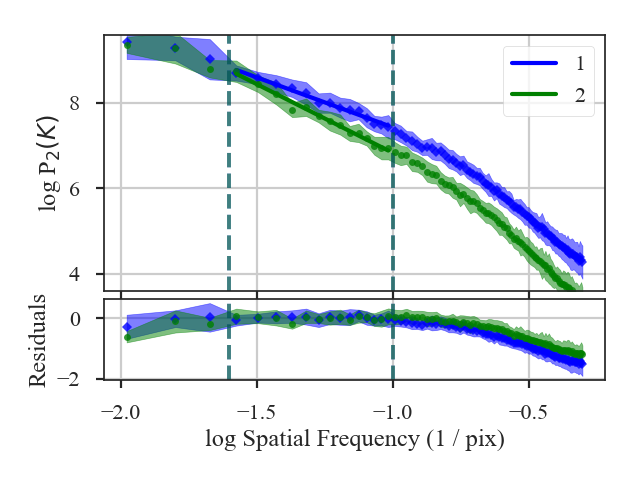

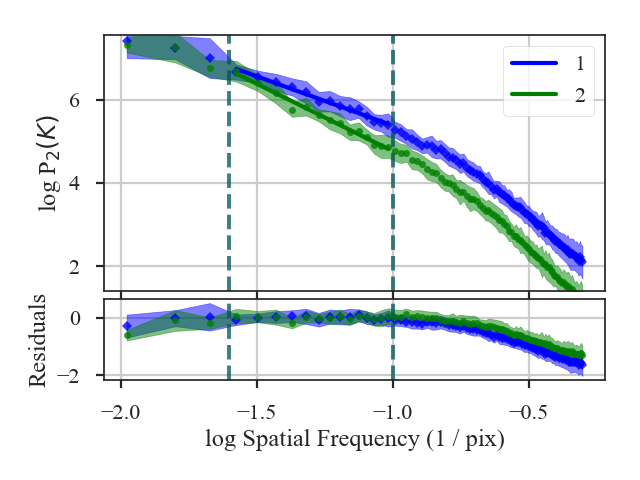

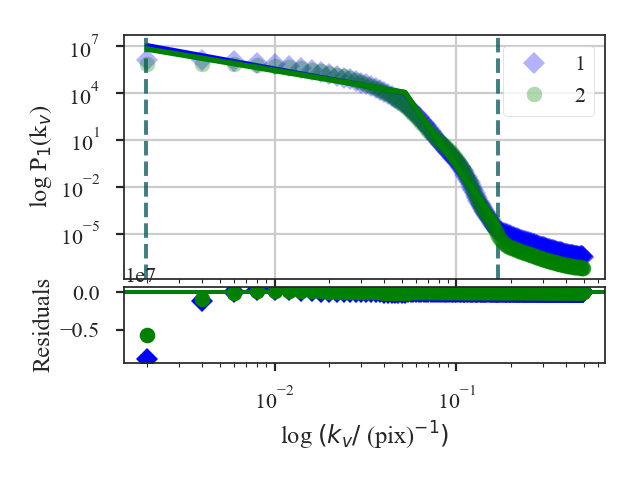

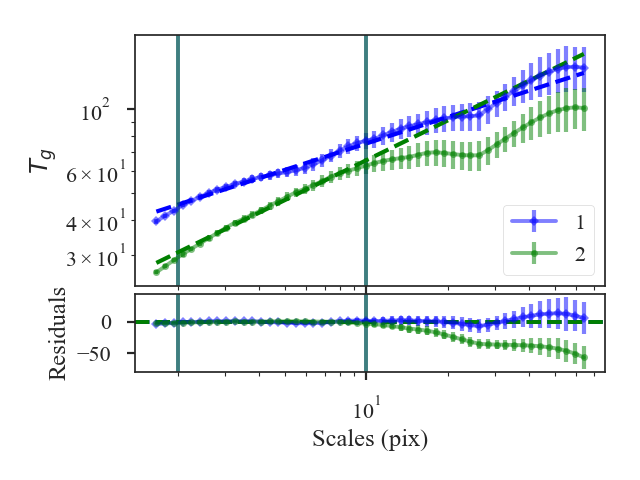

Two data sets are used for the tutorials and can be downloaded here. The data are synthetic \(^{13}{\rm CO}(2\rightarrow)1\) spectral-line data cubes from different ENZO adaptive-mesh-refinement simulations. The simulations setup and input parameters are given in Koch et al. 2017 (see Table 1). One of the data sets is a “Fiducial” and the other is a “Design” simulation; the input parameters for the solenoidal fraction, virial parameter, plasma beta, Mach number, and driving scale all differ between the two simulations.

| Parameter | Fiducial | Design |

|---|---|---|

| Solenoidal Fraction | 1/2 | 1/3 |

| Virial Parameter | 6 | 2 |

| Plasma beta | 1 | 2 |

| Mach number | 8.5 | 5 |

| Driving scale | 2-8 | 2-4 |

The simulations were performed on a \(128^3\) base grid with a fixed random turbulent driving field and the boundaries are continuous (i.e., periodic box). The data cubes were produced from one time step after gravity is turned one (\(\sim0.1\) of the free-fall time). The spectral resolution (i.e., channel width) of the cubes is \(40\) m/s.

Moment maps can also be downloaded from the data cubes with the link above. Each data cube has a zeroth (integrated intensity), first (centroid), and square of the second (line width) moment maps.

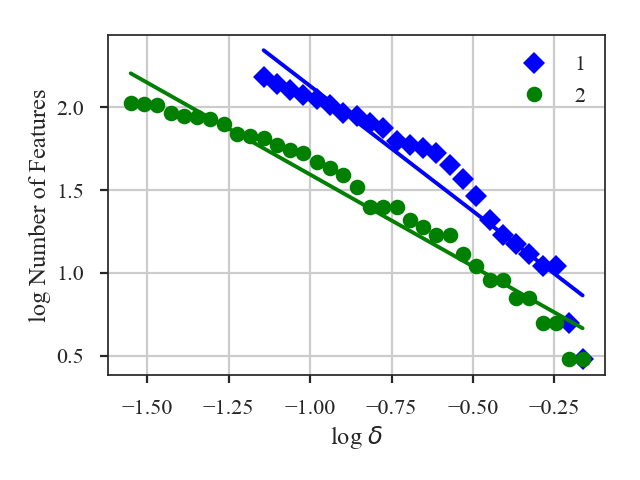

These data have a limited inertial range, which is evident in the Spatial Power Spectrum tutorial. Turbulent dissipation causes the power-spectrum to steepen on small scales and it is necessary to limit the range of scales that are fit.

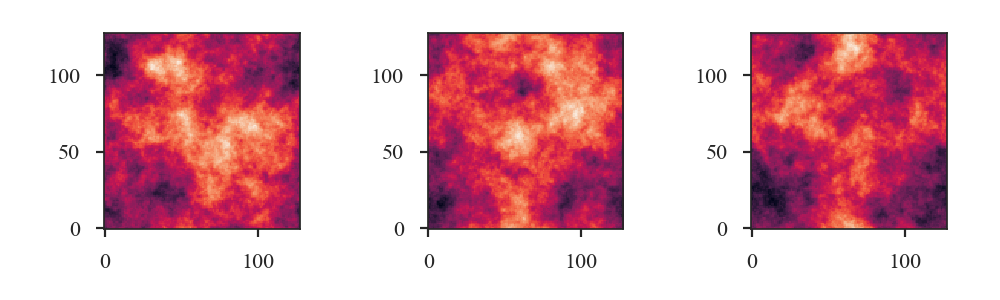

The following image shows the integrated intensity (zeroth moment) maps of the tutorial data:

.. image:: images/design_fiducial_moment0.png

Note how the integrated intensity scale varies between the two data sets.

Applying Apodizing Kernels to Data¶

Applying Fourier transforms to images with emission at the edges can lead to severe ringing effects from the Gibbs phenomenon. This can be an issue for all spatial power-spectra, including the PowerSpectrum, VCA, and MVC.

A common way to avoid this issue is to apply a window function that smoothly tapers the values at the edges of the image to zero (e.g., Stanimirovic et al. 1999). However, the shape of the window function will also affect some frequencies in the Fourier transform. This page demonstrates these effects for some common window shapes.

TurbuStat has four built-in apodizing functions based on the implementations from photutils:

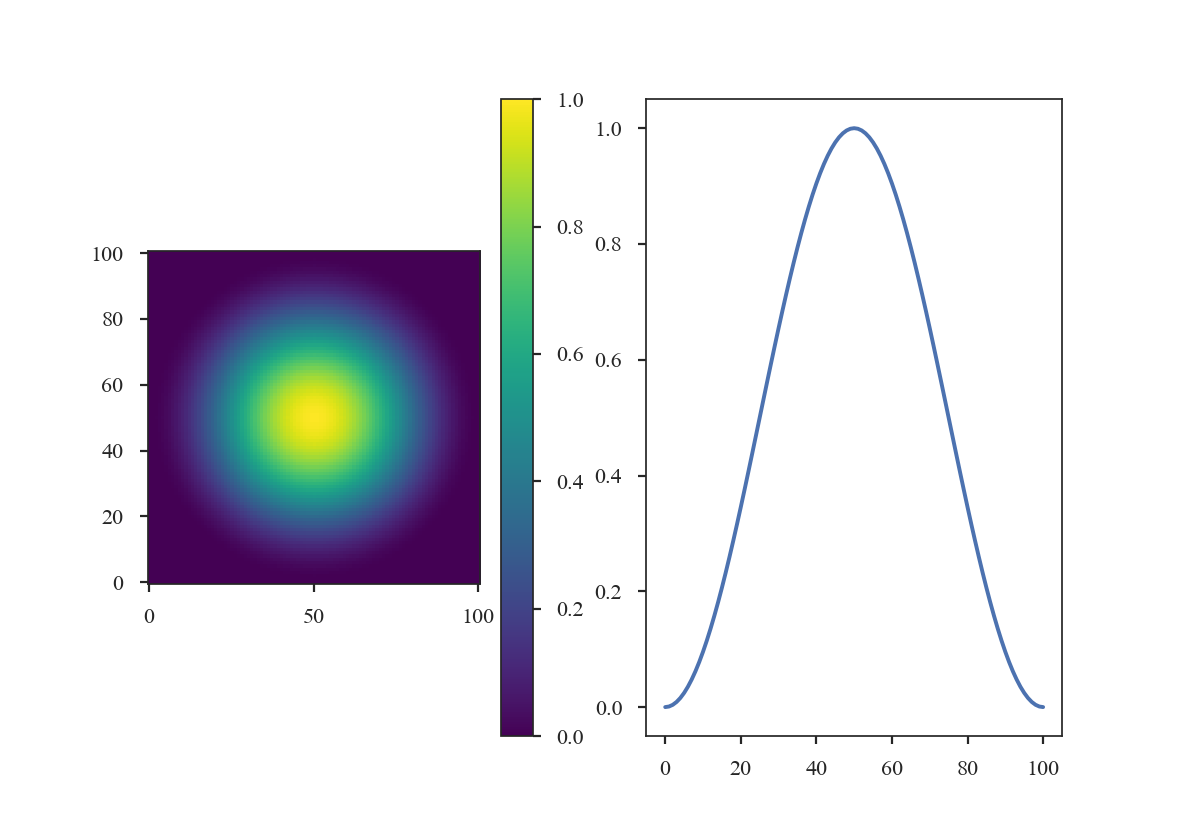

The Hanning window:

>>> from turbustat.statistics.apodizing_kernels import \

... (CosineBellWindow, TukeyWindow, HanningWindow, SplitCosineBellWindow)

>>> import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

>>> import numpy as np

>>> shape = (101, 101)

>>> taper = HanningWindow()

>>> data = taper(shape)

>>> plt.subplot(121) # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.imshow(data, cmap='viridis', origin='lower') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.colorbar() # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.subplot(122) # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.plot(data[shape[0] // 2]) # doctest: +SKIP

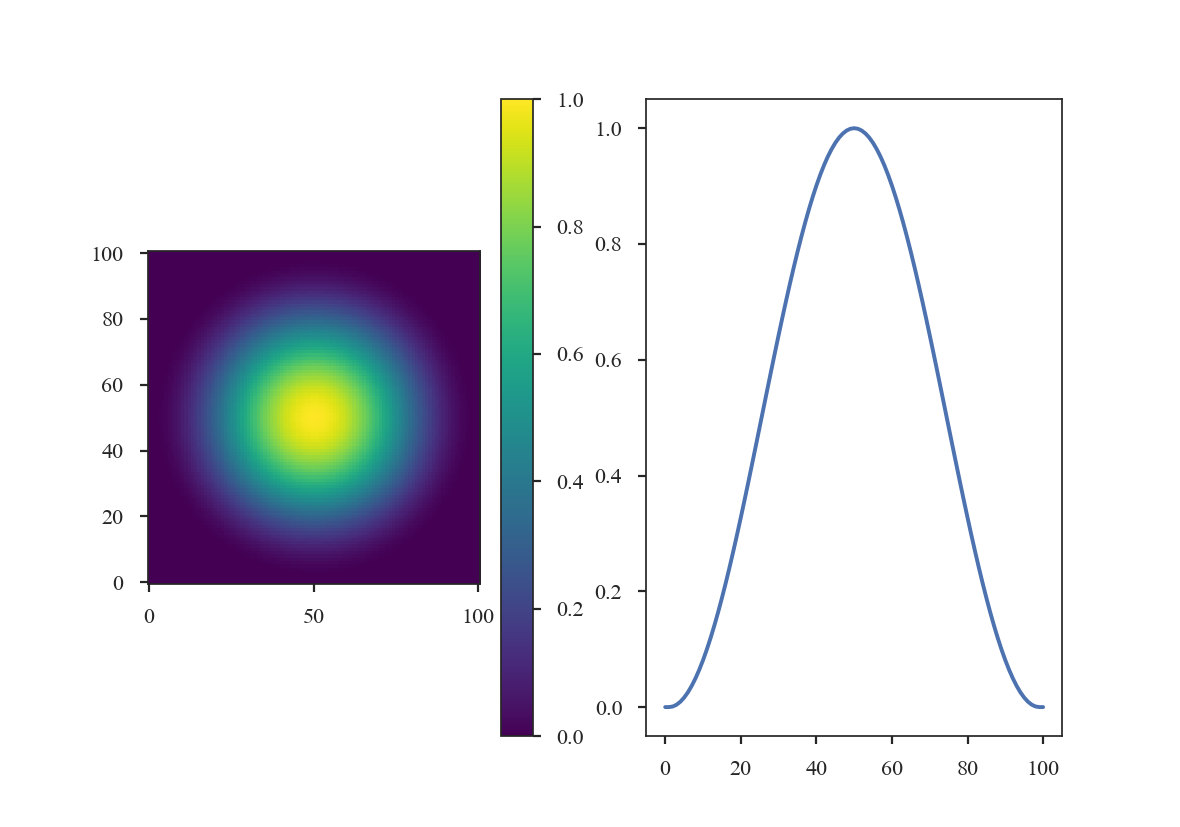

The Cosine Bell Window:

>>> taper2 = CosineBellWindow(alpha=0.8)

>>> data2 = taper2(shape)

>>> plt.subplot(121) # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.imshow(data2, cmap='viridis', origin='lower') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.colorbar() # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.subplot(122) # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.plot(data2[shape[0] // 2]) # doctest: +SKIP

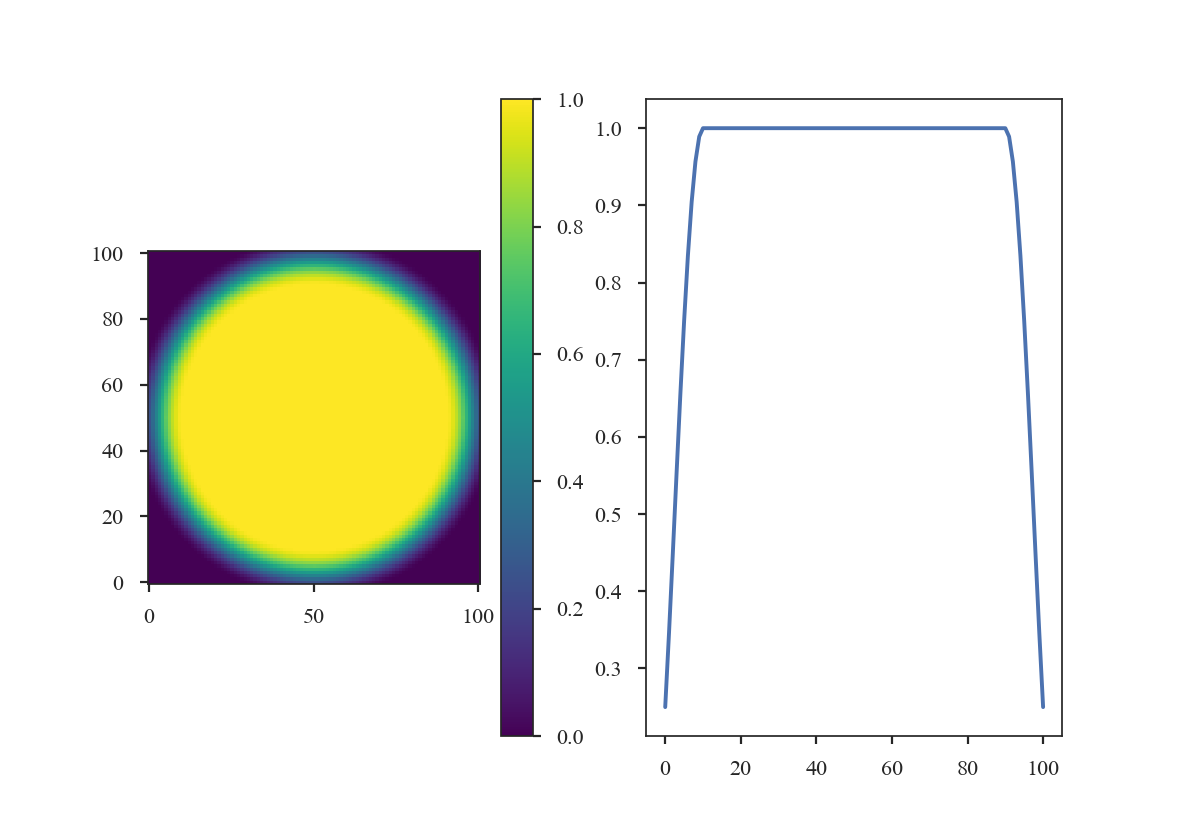

The Split-Cosine Bell Window:

>>> taper3 = SplitCosineBellWindow(alpha=0.1, beta=0.5)

>>> data3 = taper3(shape)

>>> plt.subplot(121) # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.imshow(data3, cmap='viridis', origin='lower') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.colorbar() # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.subplot(122) # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.plot(data3[shape[0] // 2]) # doctest: +SKIP

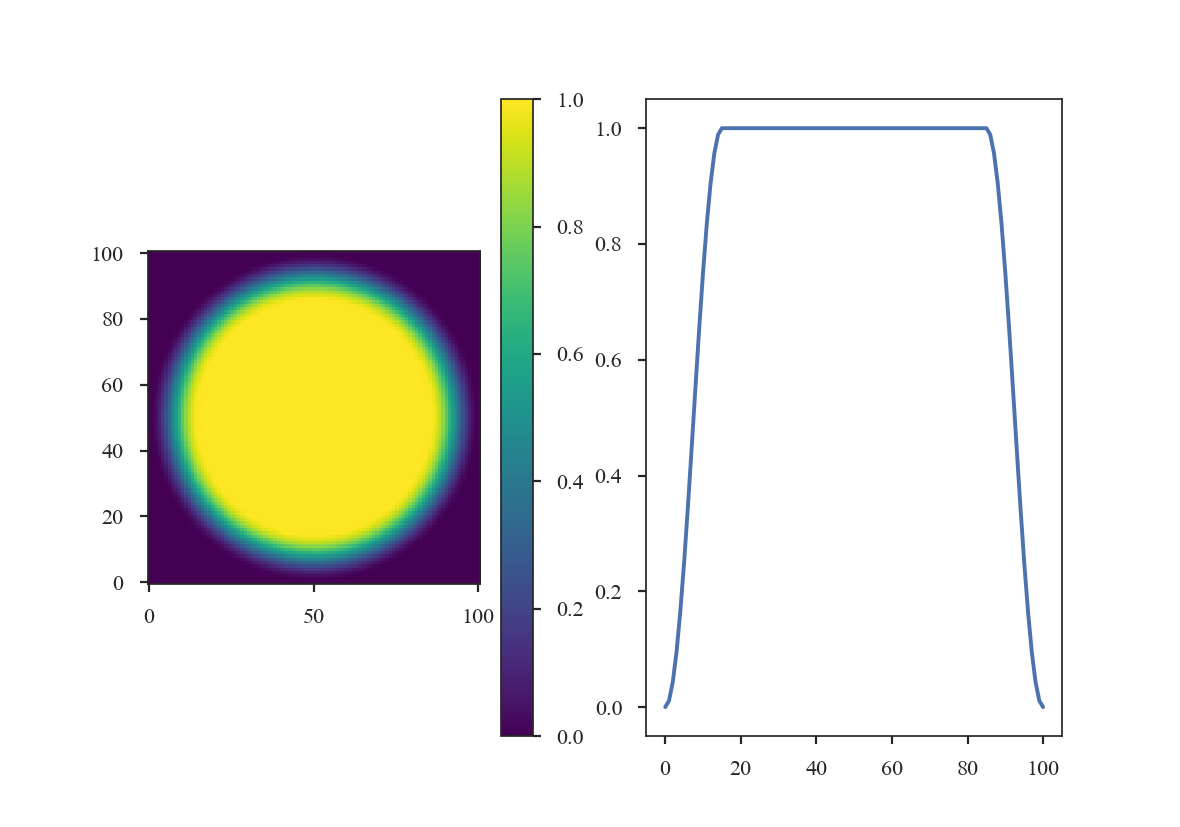

And the Tukey Window:

>>> taper4 = TukeyWindow(alpha=0.3)

>>> data4 = taper4(shape)

>>> plt.subplot(121) # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.imshow(data4, cmap='viridis', origin='lower') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.colorbar() # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.subplot(122) # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.plot(data4[shape[0] // 2]) # doctest: +SKIP

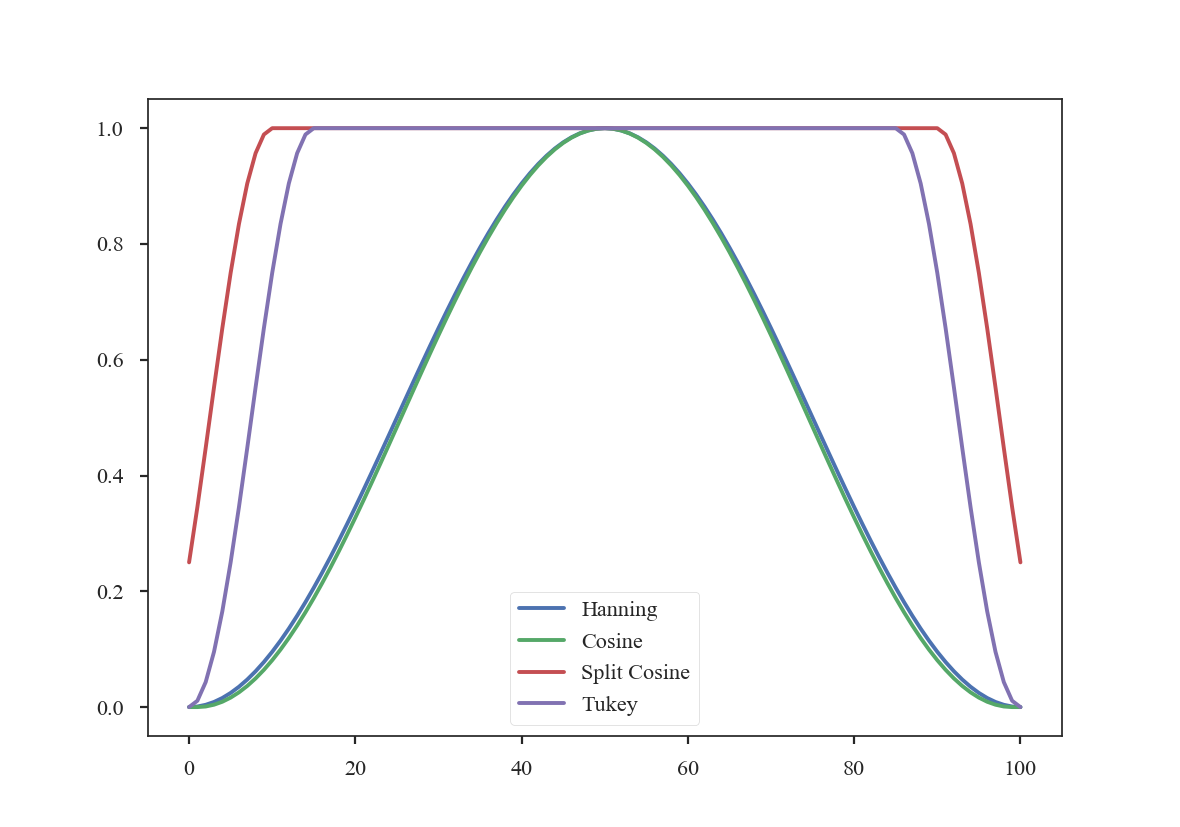

The former two windows consistently taper smoothly from the centre to the edge, while the latter two have flattened plateaus with tapering only at the edge. Plotting the 1-dimensional slices makes these differences clear:

>>> plt.plot(data[shape[0] // 2], label='Hanning') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.plot(data2[shape[0] // 2], label='Cosine') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.plot(data3[shape[0] // 2], label='Split Cosine') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.plot(data4[shape[0] // 2], label='Tukey') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.legend(frameon=True) # doctest: +SKIP

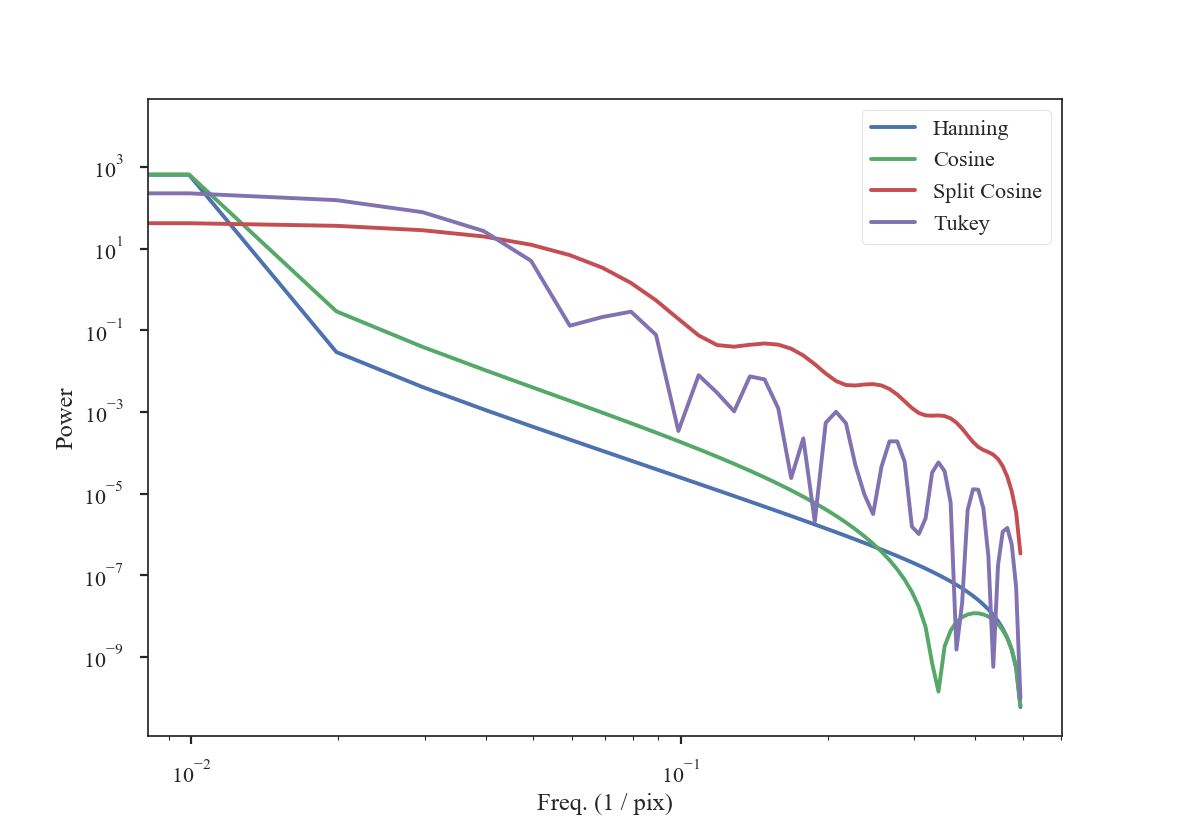

To get an idea of how these apodizing functions affect the data, we can examine their power-spectra:

>>> freqs = np.fft.rfftfreq(shape[0])

>>> plt.loglog(freqs, np.abs(np.fft.rfft(data[shape[0] // 2]))**2, label='Hanning') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.loglog(freqs, np.abs(np.fft.rfft(data2[shape[0] // 2]))**2, label='Cosine') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.loglog(freqs, np.abs(np.fft.rfft(data3[shape[0] // 2]))**2, label='Split Cosine') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.loglog(freqs, np.abs(np.fft.rfft(data4[shape[0] // 2]))**2, label='Tukey') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.legend(frameon=True) # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.xlabel("Freq. (1 / pix)") # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.ylabel("Power") # doctest: +SKIP

The smoothly-varying windows (Hanning and Cosine) have power-spectra that consistently decrease the power. This means that the use of a Hanning or Cosine window will affect the shape of power-spectra over a larger range of frequencies than the Split-Cosine or Tukey windows.

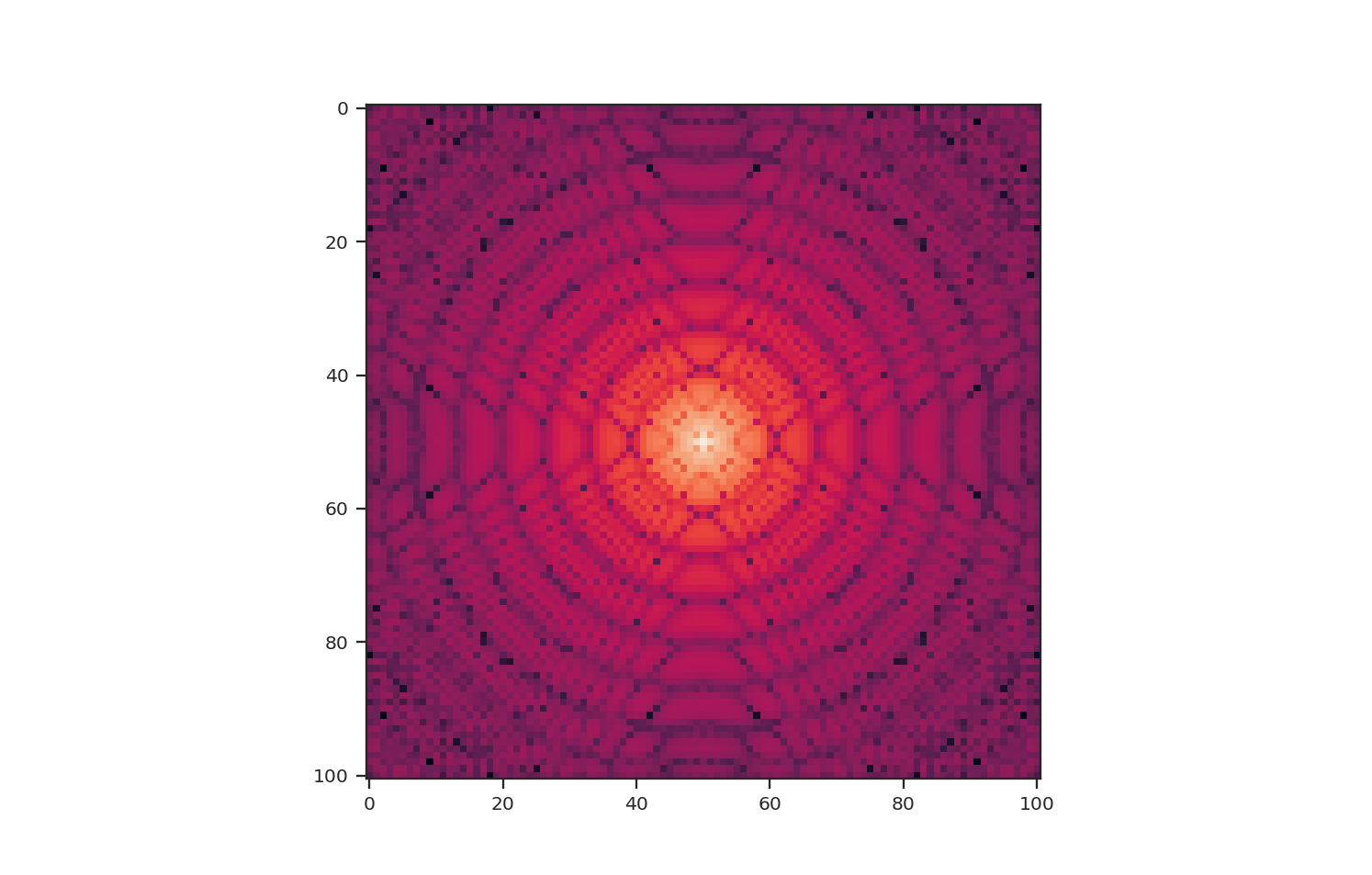

These apodizing kernels are azimuthally-symmetric. However, as an example, the 2D power-spectrum of the Tukey Window, which is used below, has this structure:

>>> plt.imshow(np.log10(np.fft.fftshift(np.abs(np.fft.fft2(data4))**2)))

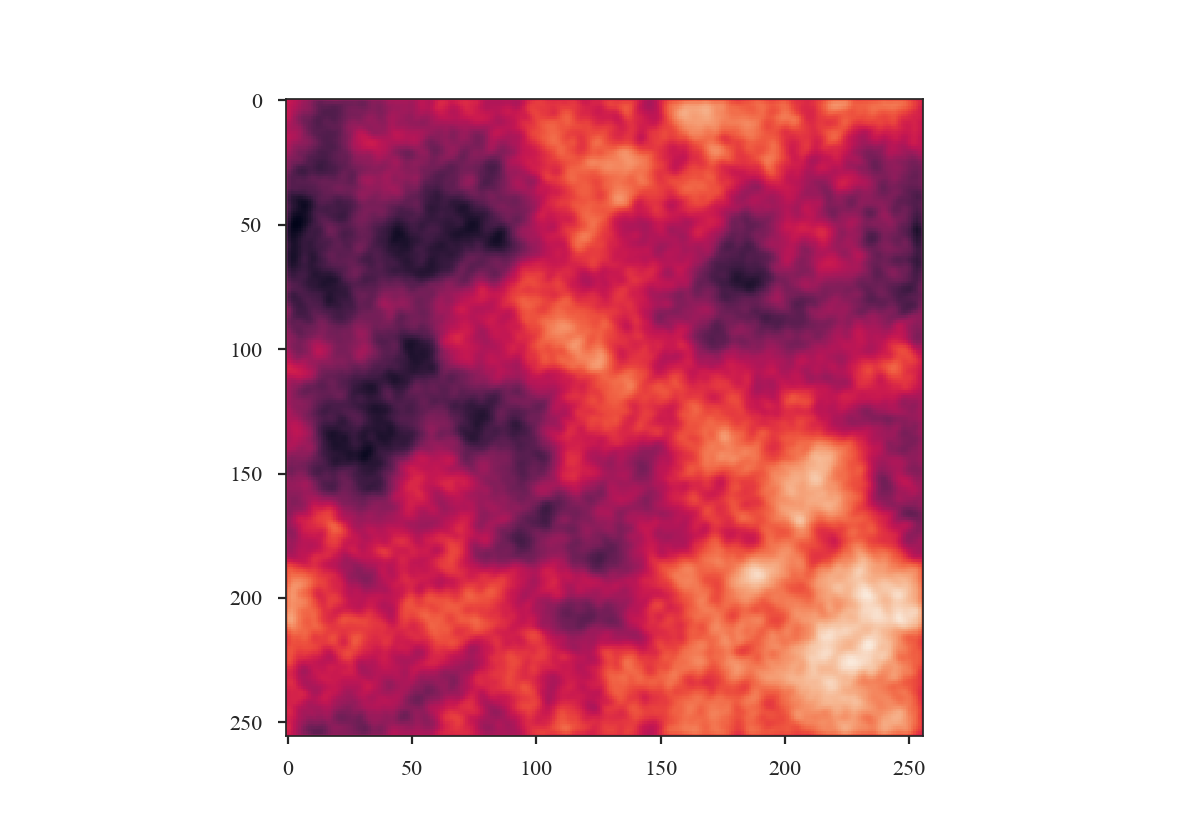

As an example, we will compare the effect each of the windows has on a red-noise image.

>>> from turbustat.simulator import make_extended

>>> from turbustat.io.sim_tools import create_fits_hdu

>>> from astropy import units as u

>>> # Image drawn from red-noise

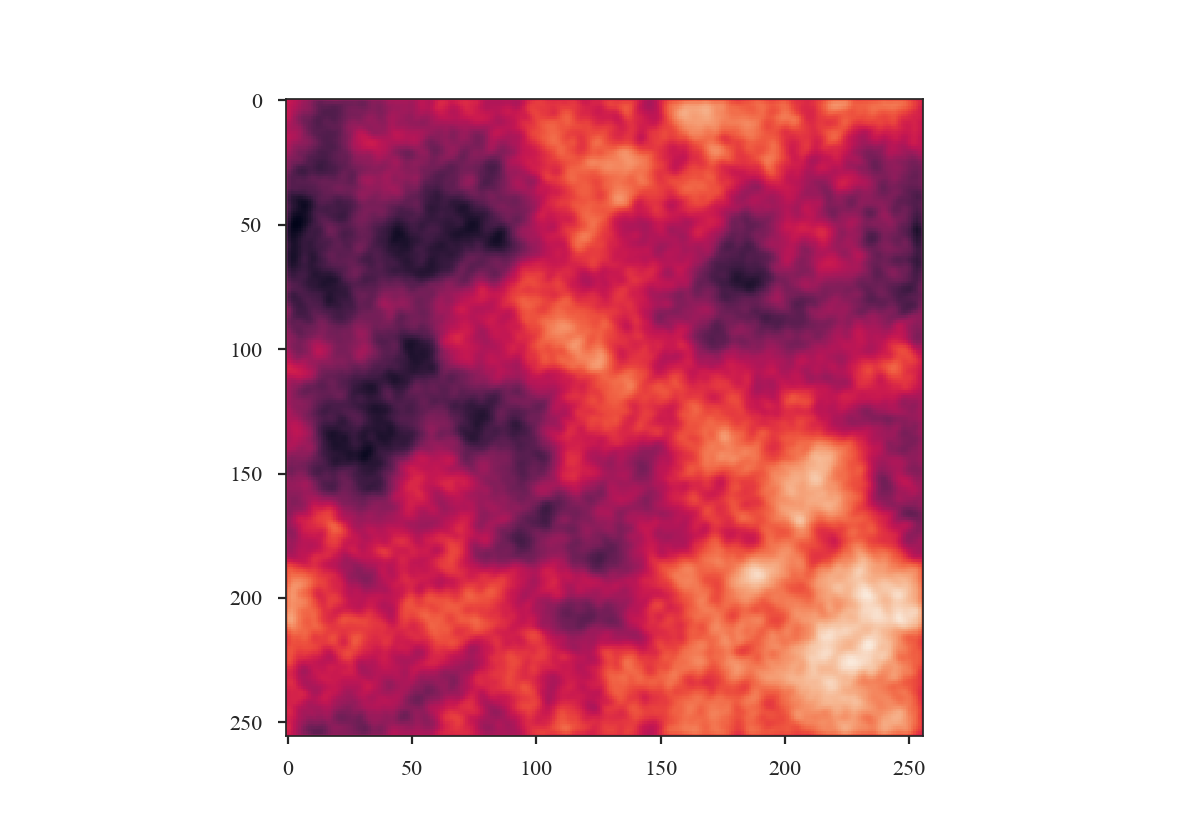

>>> rnoise_img = make_extended(256, powerlaw=3.)

>>> # Define properties to generate WCS information

>>> pixel_scale = 3 * u.arcsec

>>> beamfwhm = 3 * u.arcsec

>>> imshape = rnoise_img.shape

>>> restfreq = 1.4 * u.GHz

>>> bunit = u.K

>>> # Create a FITS HDU

>>> plaw_hdu = create_fits_hdu(rnoise_img, pixel_scale, beamfwhm, imshape, restfreq, bunit)

>>> plt.imshow(plaw_hdu.data) # doctest: +SKIP

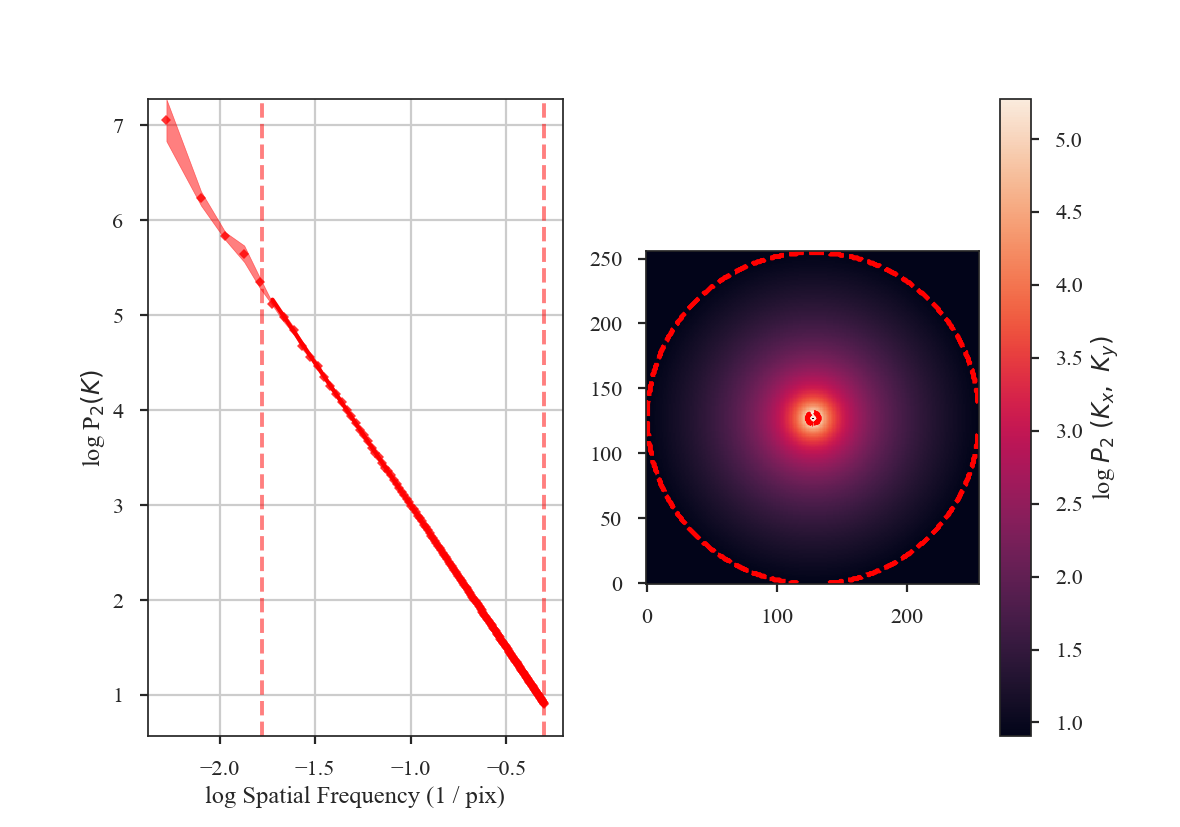

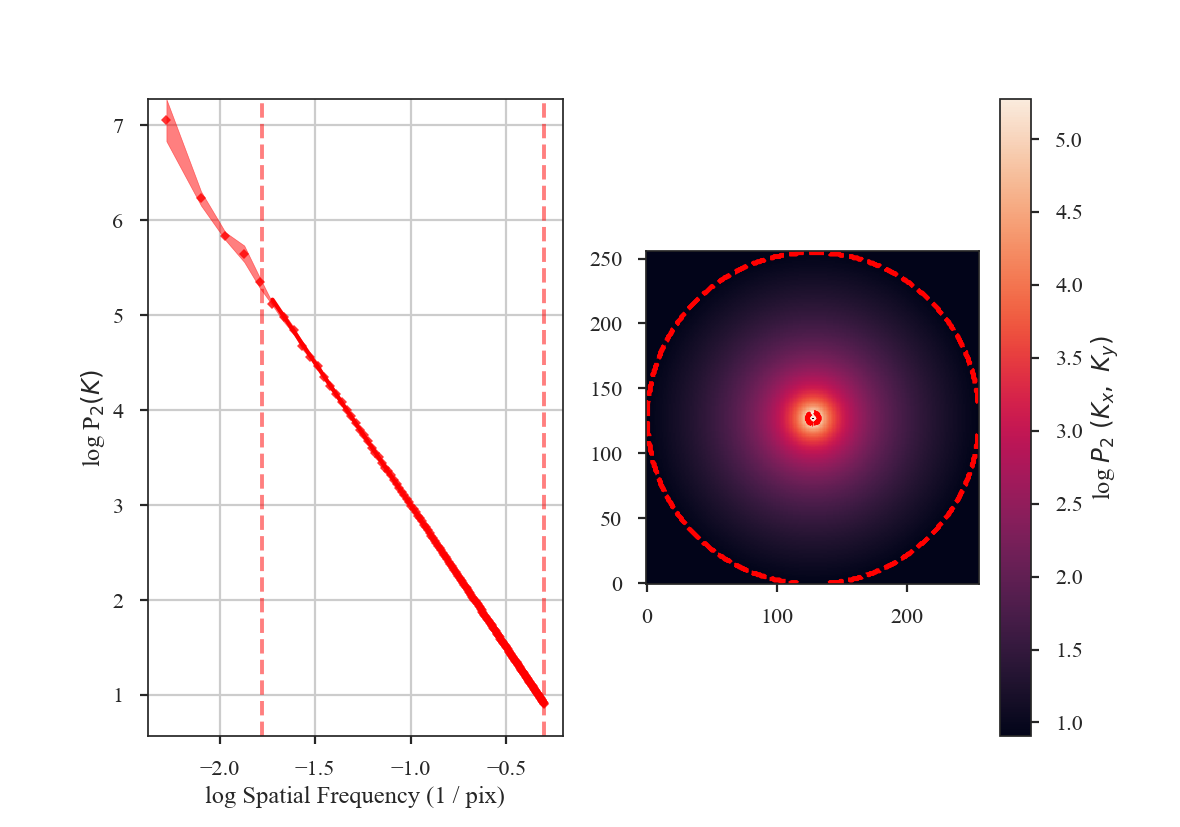

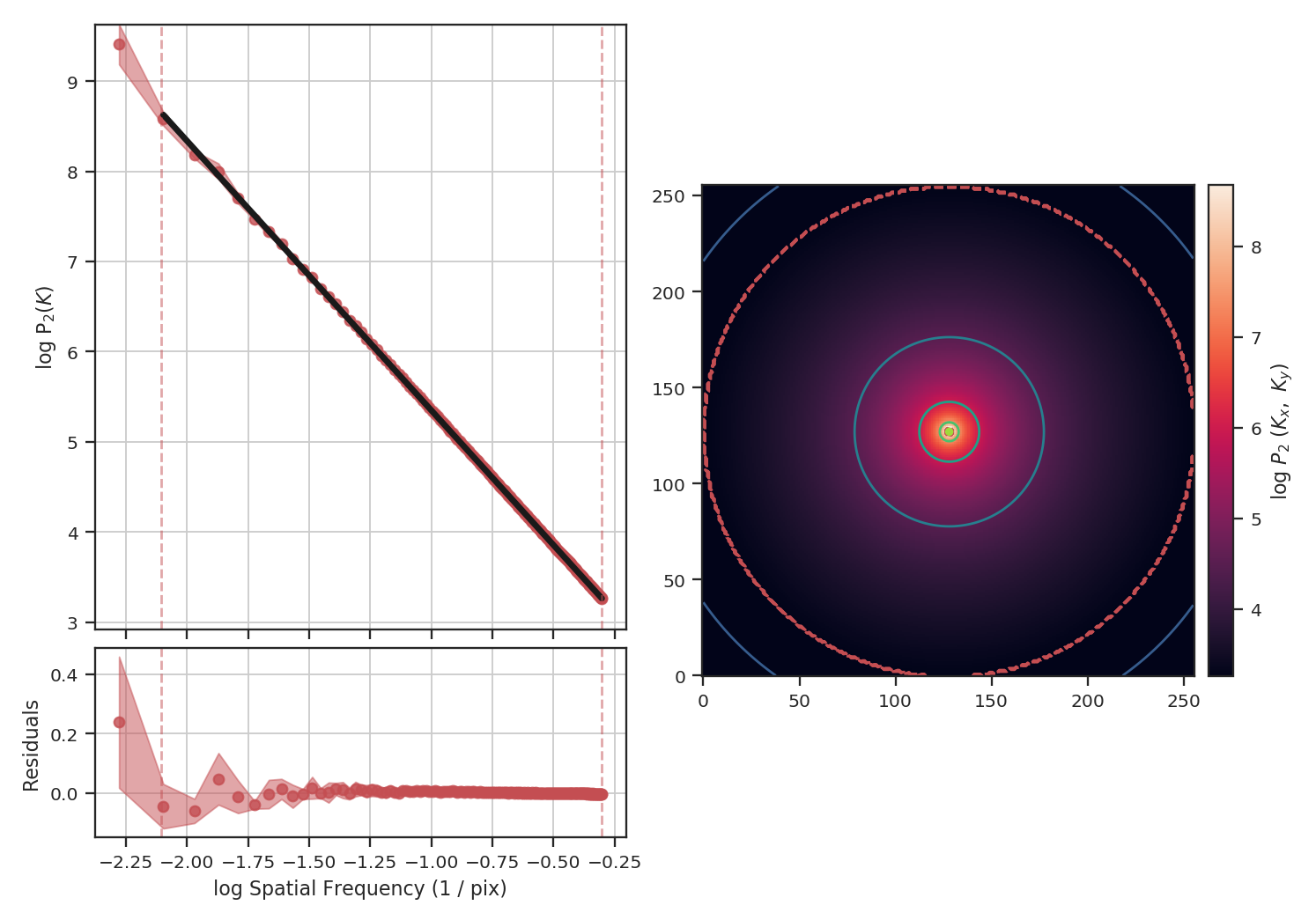

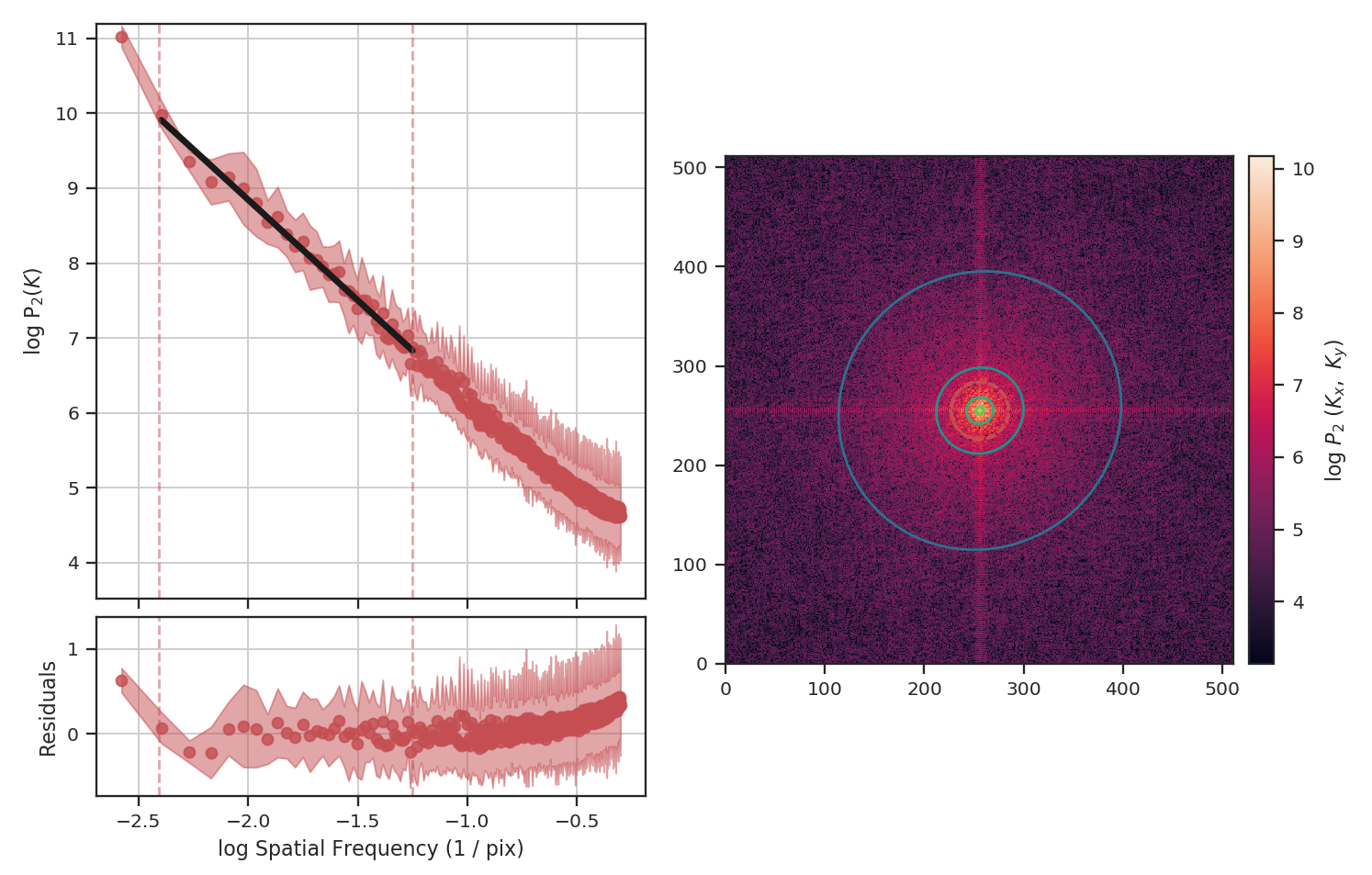

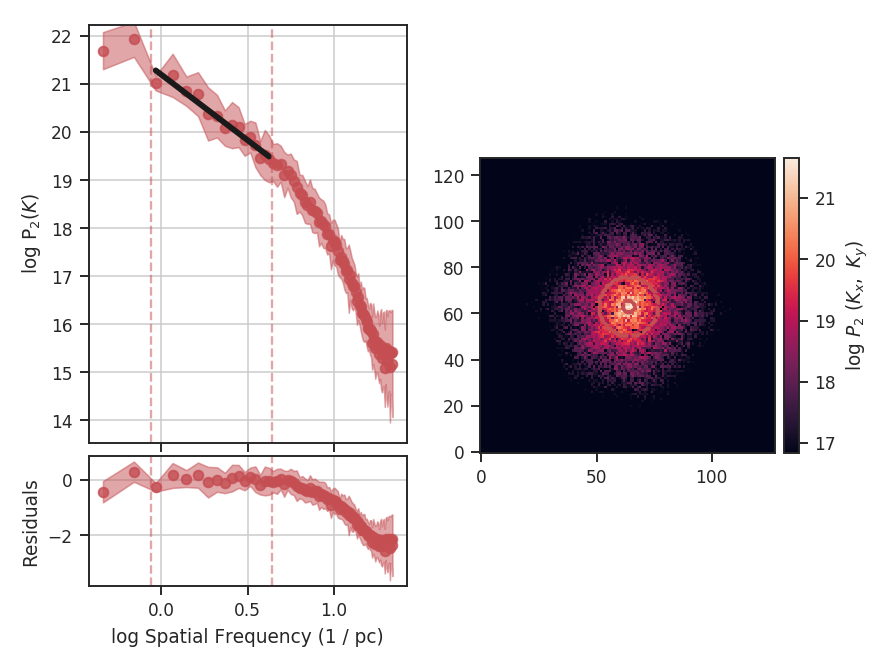

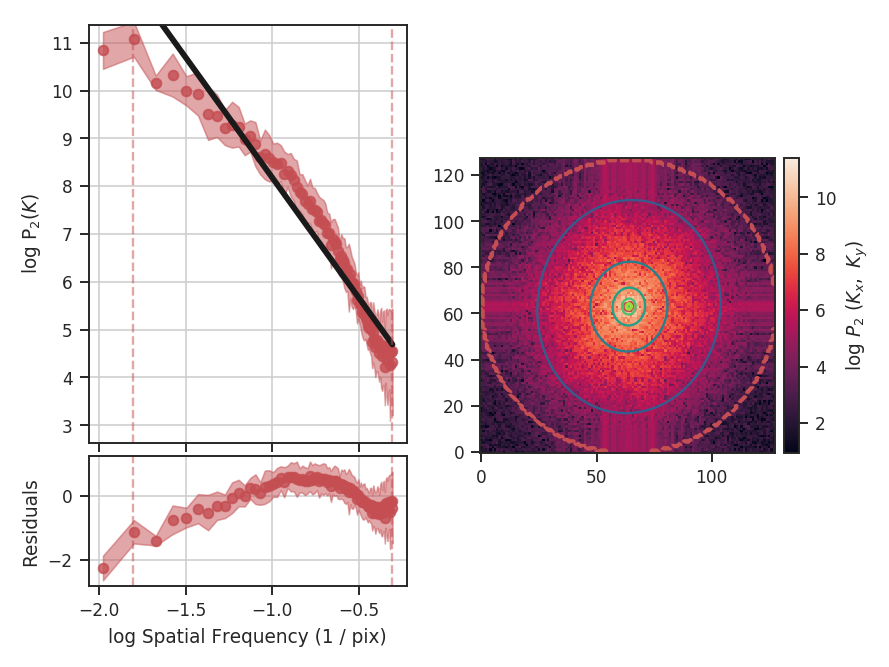

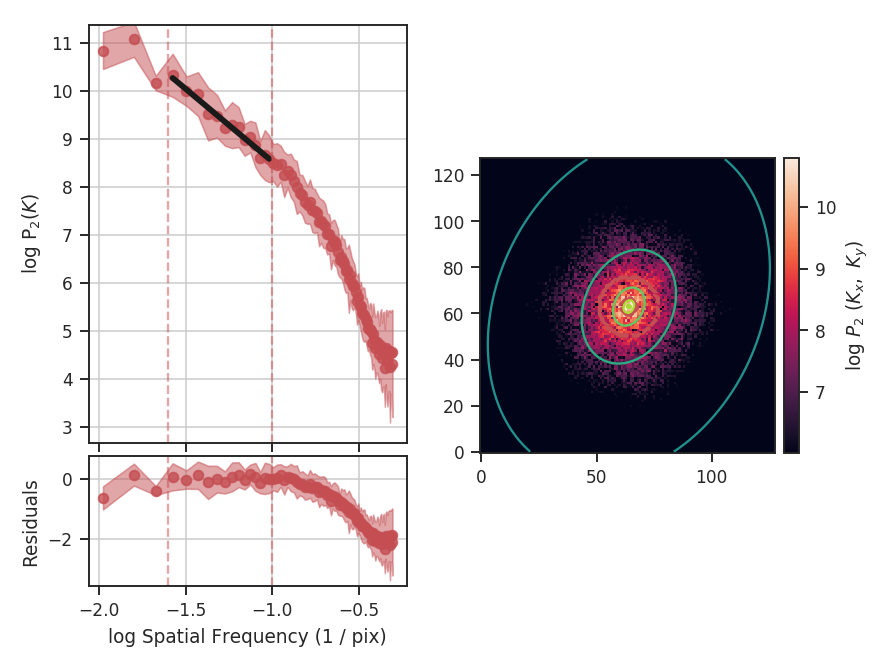

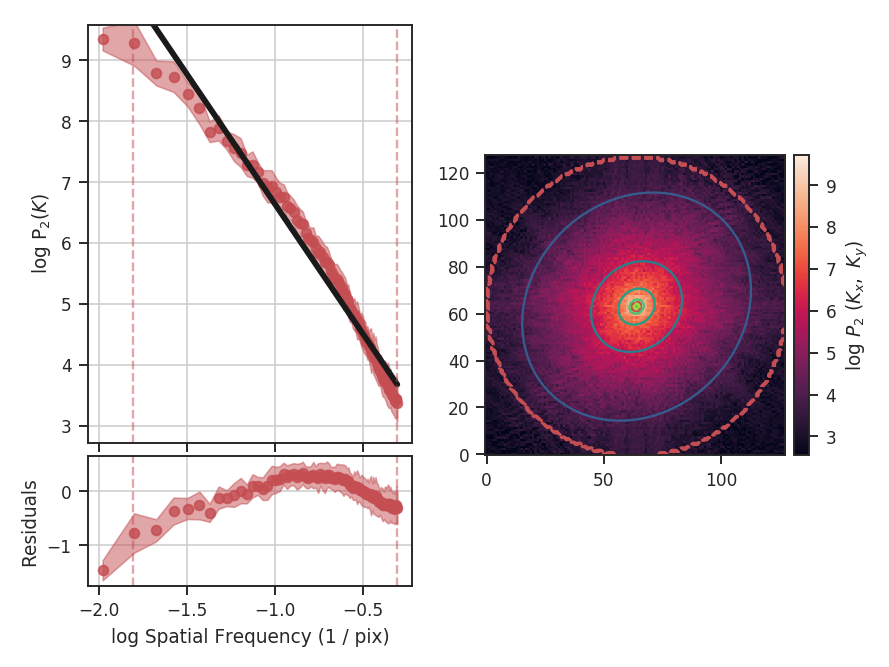

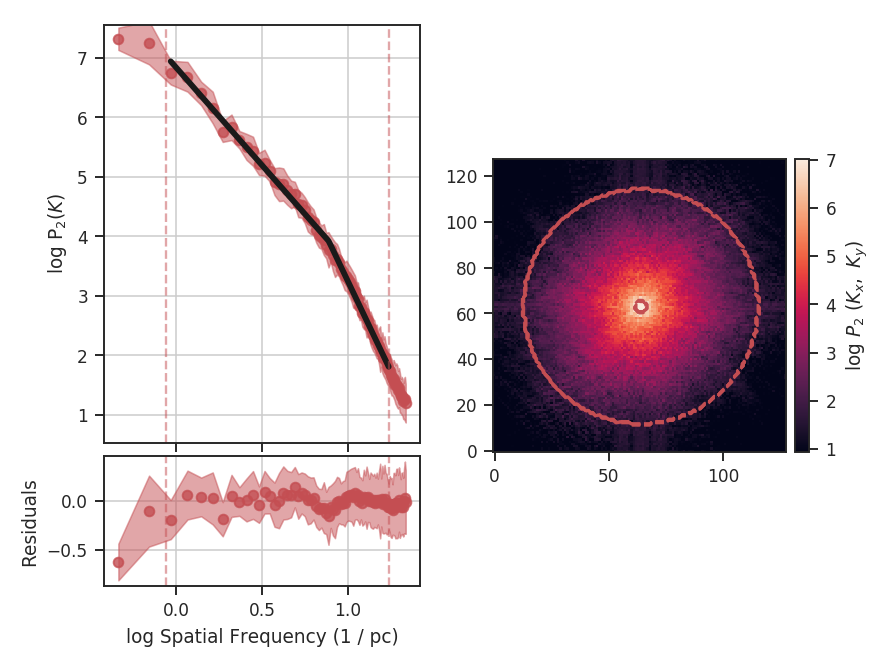

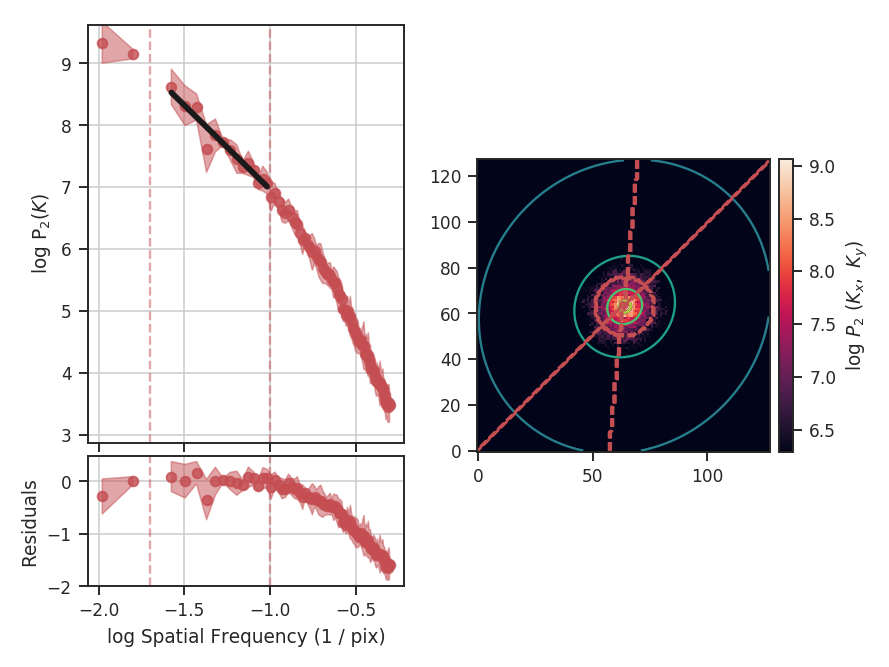

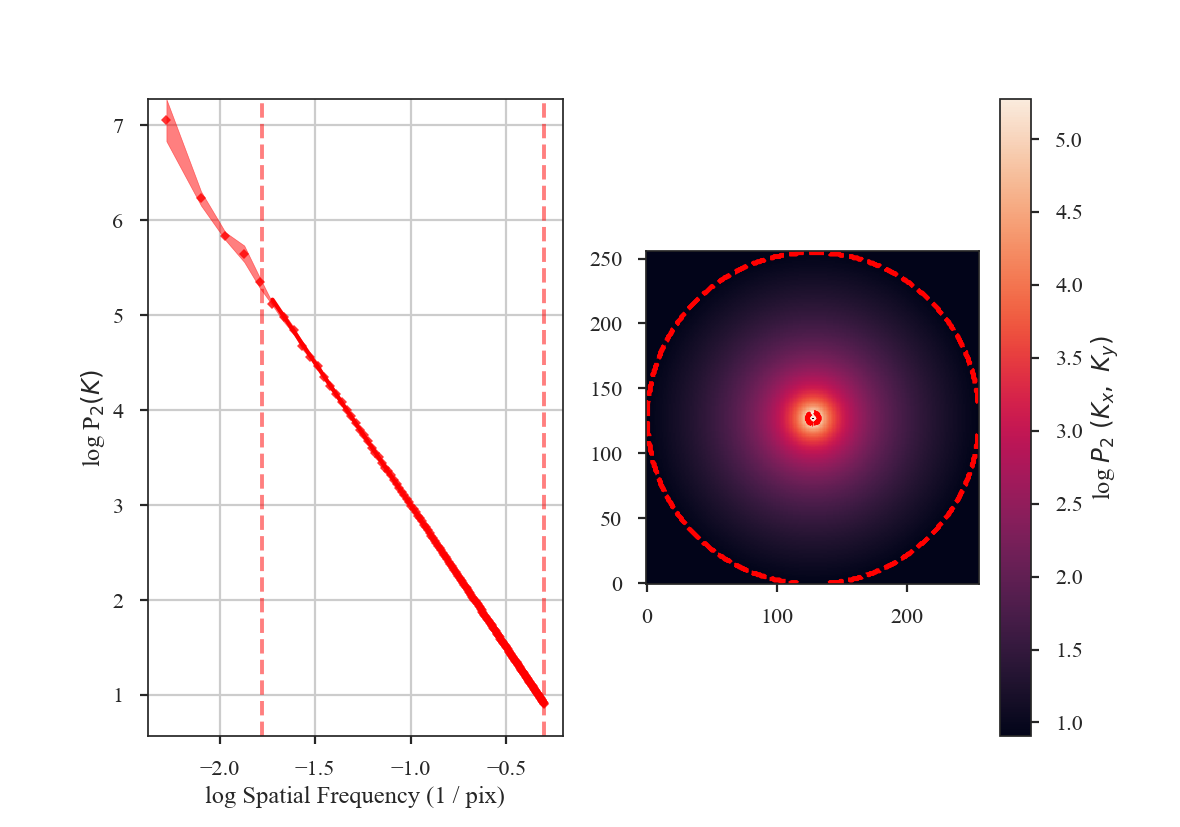

The image should have a power-spectrum index of 3 with mean values centred at 0. By running PowerSpectrum, we can confirm that the index is indeed 3 (see the variable x1 in the output):

>>> from turbustat.statistics import PowerSpectrum

>>> pspec = PowerSpectrum(plaw_hdu)

>>> pspec.run(verbose=True, radial_pspec_kwargs={'binsize': 1.0},

... fit_2D=False,

... low_cut=1. / (60 * u.pix)) # doctest: +SKIP

OLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: y R-squared: 1.000

Model: OLS Adj. R-squared: 1.000

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 8.070e+06

Date: Thu, 21 Jun 2018 Prob (F-statistic): 0.00

Time: 11:43:47 Log-Likelihood: 701.40

No. Observations: 177 AIC: -1399.

Df Residuals: 175 BIC: -1392.

Df Model: 1

Covariance Type: nonrobust

==============================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const 0.0032 0.001 3.952 0.000 0.002 0.005

x1 -2.9946 0.001 -2840.850 0.000 -2.997 -2.992

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 252.943 Durbin-Watson: 1.077

Prob(Omnibus): 0.000 Jarque-Bera (JB): 26797.433

Skew: -5.963 Prob(JB): 0.00

Kurtosis: 62.087 Cond. No. 4.55

==============================================================================

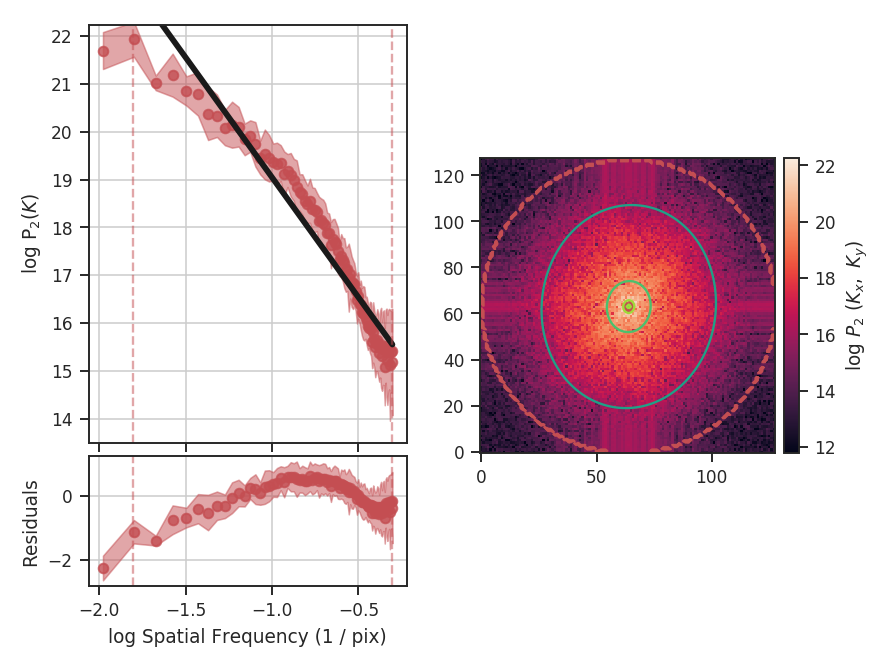

The slope is nearly 3, as expected. Note that we have limited the range of frequencies fit over to avoid the largest scales using the parameter low_cut. Also note that there is a “hole” in the centre of the 2D power-spectrum on the right panel in the image. This is the zero-frequency of the image and scales with the mean value of the image. Since this image is centred at 0, there is no power at the zero-frequency point in the centre of the 2D power-spectrum.

From the figure, it is clear that the samples on larger scales deviate from a power-law. This deviation is a result of the lack of samples on these large-scales. It can be avoided by increasing the size of the radial bins, but we will use small bins here to highlight the effect of the apodizing kernels on the power-spectrum shape.

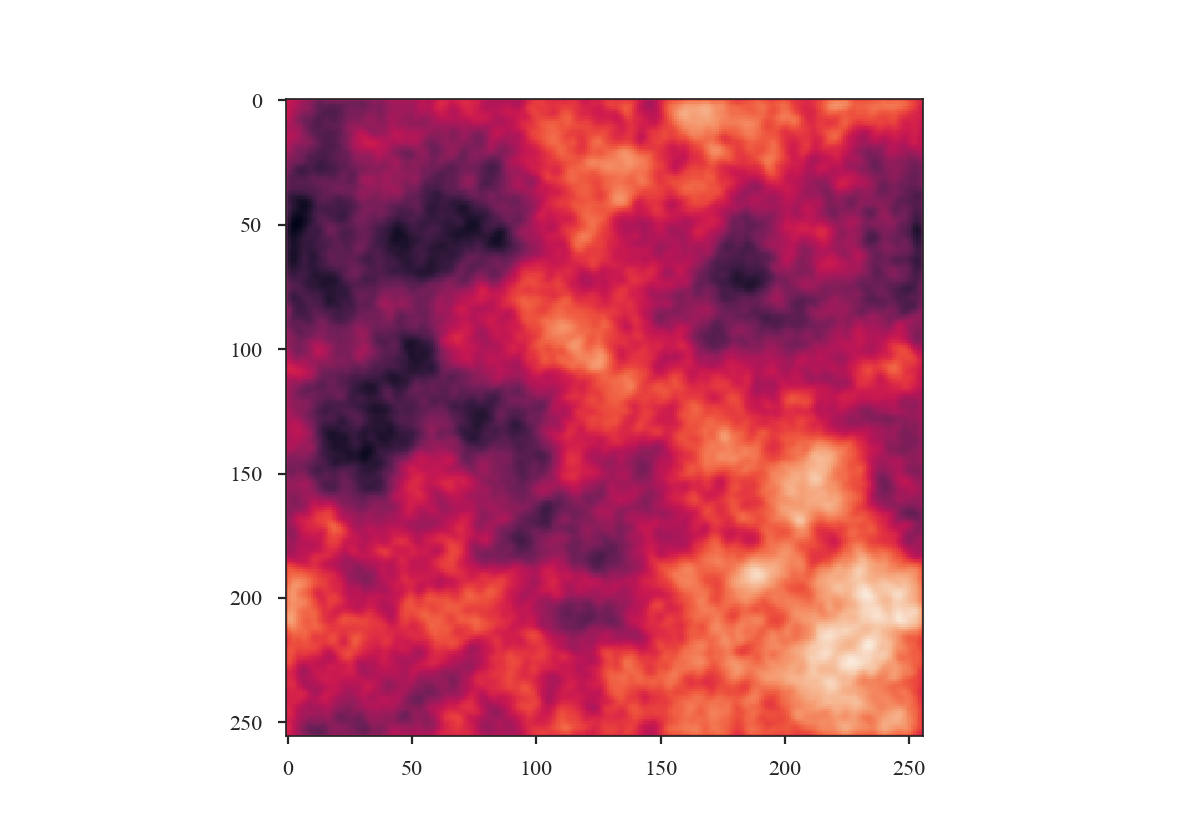

Before exploring the effect of the apodizing kernels, we can demonstrate the need for an apodizing kernel by taking a slice of the red-noise image, such that the edges are no longer periodic.

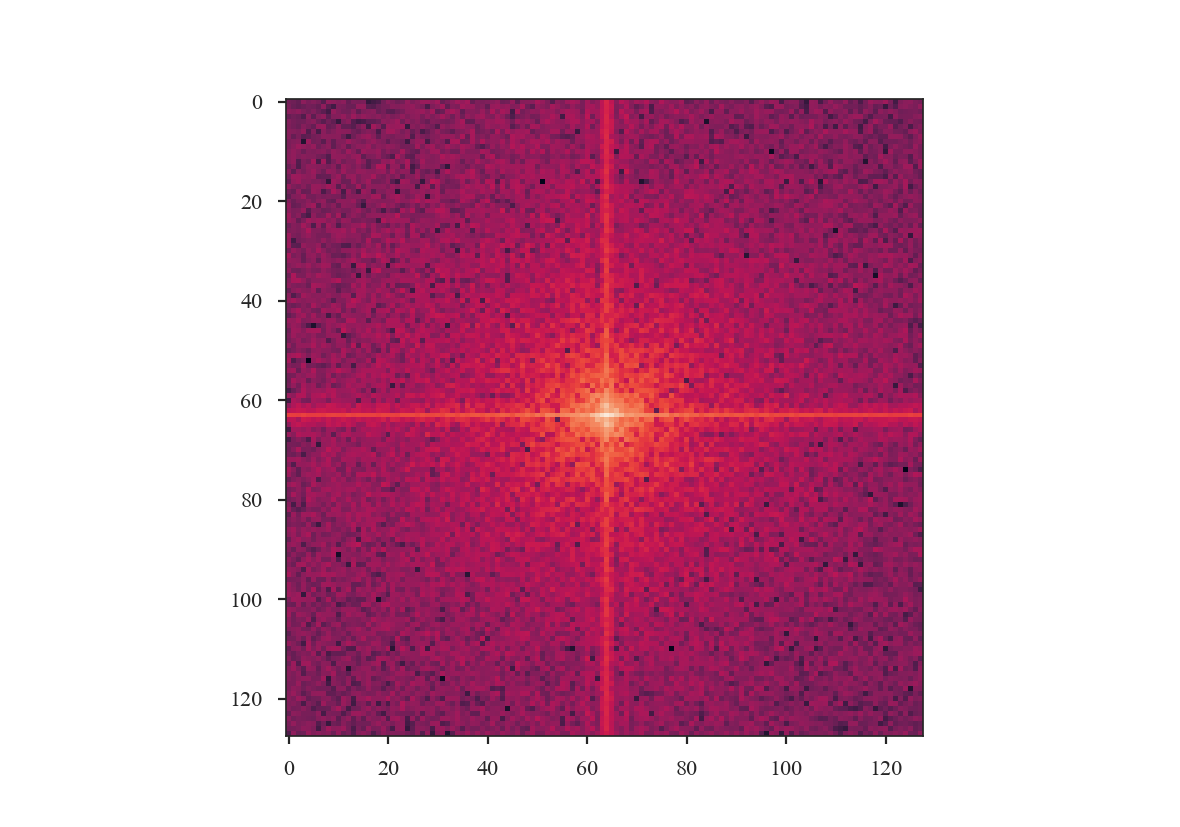

>>> pspec_partial = PowerSpectrum(rnoise_img[:128, :128], header=plaw_hdu.header).run(verbose=False, fit_2D=False, low_cut=1 / (60. * u.pix))

>>> plt.imshow(np.log10(pspec_partial.ps2D)) # doctest: +SKIP

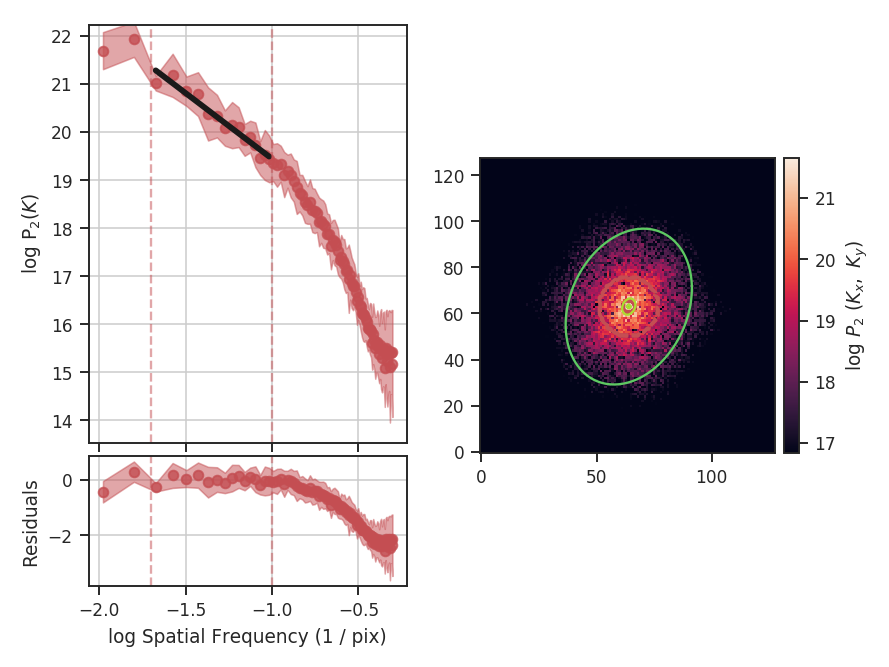

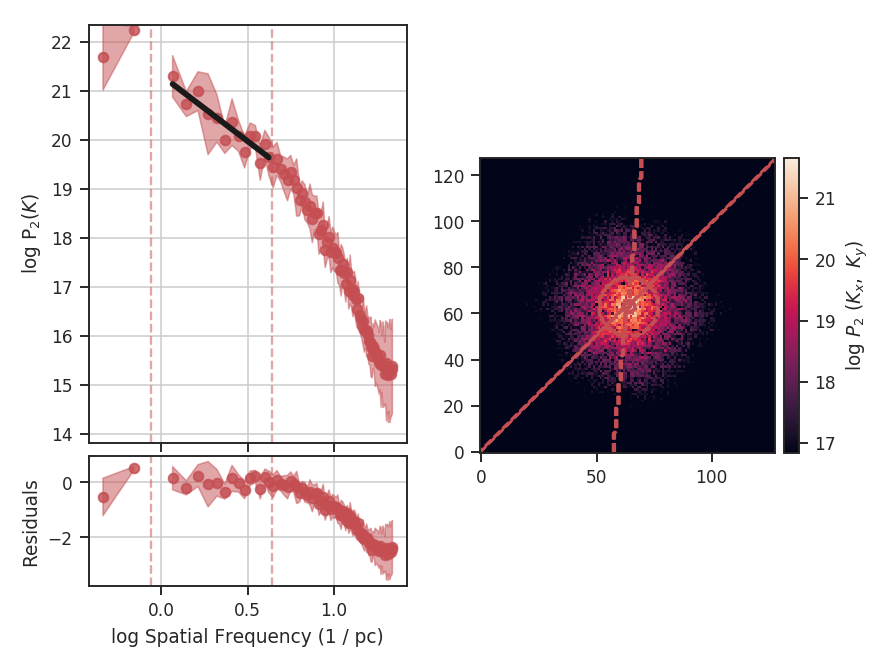

The ringing at large scales is evident in the cross-shape in the 2D power spectrum. This affects the azimuthally-averaged 1D power-spectrum, and therefore the slope of the power-spectrum. Tapering the values at the edges can account for this.

The power-spectrum also appears noisier than the original, yet no noise has been added to the image. This is due to the image no longer being fully sampled for a power-spectrum index of \(3\). This index has most of its power on large scales, so the most prominent structure is on large scales, and slicing has removed significant portions of the large-scale structure. Also note that there is no “hole” at the centre of the 2D power-spectrum since the mean of the sliced image is not \(0\).

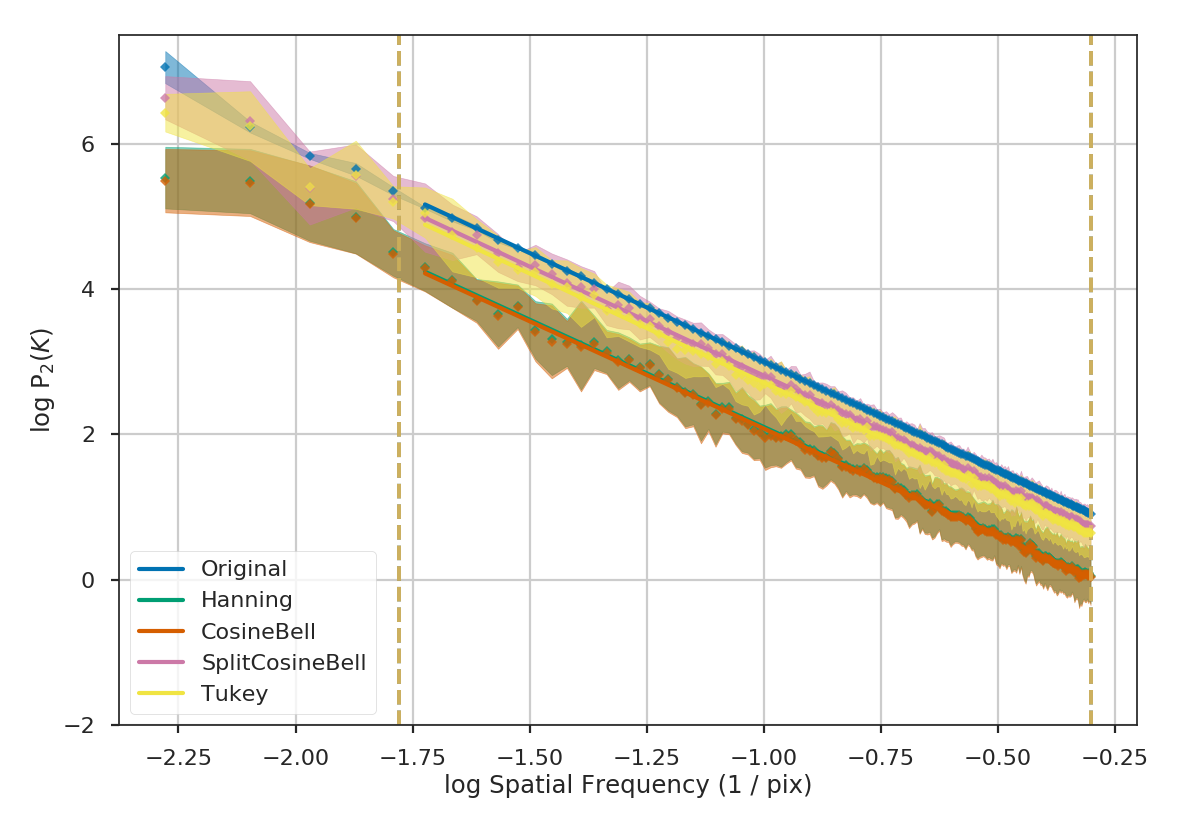

We will now compare the how the different apodizing kernels change the power-spectrum shape. The power-spectra will be fit up to scales of \(60\) pixels (or a frequency of \(0.01667\)), avoiding scales that are poorly sampled in the sliced image. The following code computes the power-spectrum of the sliced image using all four of the apodizing kernels shown above.

>>> pspec2 = PowerSpectrum(plaw_hdu)

>>> pspec2.run(verbose=False, radial_pspec_kwargs={'binsize': 1.0},

... fit_2D=False,

... low_cut=1. / (60 * u.pix),

... apodize_kernel='hanning',) # doctest: +SKIP

>>> pspec3 = PowerSpectrum(plaw_hdu)

>>> pspec3.run(verbose=False, radial_pspec_kwargs={'binsize': 1.0},

... fit_2D=False,

... low_cut=1. / (60 * u.pix),

... apodize_kernel='cosinebell', alpha=0.98) # doctest: +SKIP

>>> pspec4 = PowerSpectrum(plaw_hdu)

>>> pspec4.run(verbose=False, radial_pspec_kwargs={'binsize': 1.0},

... fit_2D=False,

... low_cut=1. / (60 * u.pix),

... apodize_kernel='splitcosinebell', alpha=0.3, beta=0.8) # doctest: +SKIP

>>> pspec5 = PowerSpectrum(plaw_hdu)

>>> pspec5.run(verbose=False, radial_pspec_kwargs={'binsize': 1.0},

... fit_2D=False,

... low_cut=1. / (60 * u.pix),

... apodize_kernel='tukey', alpha=0.3) # doctest: +SKIP

For brevity, we will plot only the 1D power-spectra using the different apodizing kernels.

>>> # Change the colours and comment these lines if you don't use seaborn

>>> import seaborn as sb # doctest: +SKIP

>>> col_pal = sb.color_palette() # doctest: +SKIP

>>> pspec.plot_fit(color=col_pal[0], label='Original') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> pspec2.plot_fit(color=col_pal[1], label='Hanning') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> pspec3.plot_fit(color=col_pal[2], label='CosineBell') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> pspec4.plot_fit(color=col_pal[3], label='SplitCosineBell') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> pspec5.plot_fit(color=col_pal[4], label='Tukey') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.legend(frameon=True, loc='lower left') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.ylim([2, 9.5]) # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.tight_layout() # doctest: +SKIP

Comparing the different power spectra with different apodizing kernels, the only variations occur on large scales. However, as noted above, the large frequencies suffer from a lack of samples and tend to have underestimated errors. The well-sampled range of frequencies, from 1 to 60 pixels, have a slope that is relatively unaffected regardless of the apodizing kernel that is used. The fitted slopes are:

>>> print("Original: {0:.2f} \nHanning: {1:.2f} \nCosineBell: {2:.2f} \n"

... "SplitCosineBell: {3:.2f} "

... "\nTukey: {4:.2f}".format(pspec.slope,

... pspec2.slope,

... pspec3.slope,

... pspec4.slope,

... pspec5.slope)) # doctest: +SKIP

Original: -3.00

Hanning: -2.95

CosineBell: -2.95

SplitCosineBell: -3.00

Tukey: -3.01

Each of the slopes are close to the expected value of \(-3\). The Cosine and Hanning kernels moderately flatten the power-spectra on all scales. This is evident from the figure above comparing the 1D power-spectra of the four kernels.

Warning

The range of frequencies affected by the apodizing kernel depends on the properties of the kernel used. The shape of the kernels are controlled by the \(\alpha\) and/or \(\beta\) parameters (see above). Narrower shapes will tend to have a larger effect on the power-spectrum. It is prudent to check the effect of the apodizing kernel by comparing different choices for the shape!

The optimal choice of apodizing kernel, and the shape parameters for that kernel, will depend on the data that is being used. If there is severe ringing in the power-spectrum, the Hanning or CosineBell kernels are most effective at removing ringing. However, as shown above, these kernels bias the slope at all frequencies. The SplitCosineBell or Tukey are not as affective at removing ringing in extreme cases but they do only bias the shape of the power-spectrum at large frequencies (\(\sim1/2\) of the image size and larger).

Accounting for the beam shape¶

Warning

The beam size of an observation introduces artificial correlations into the data on scales near to and below the beam size. This affects the shape of various turbulence statistics that measure spatial properties (Spatial Power-Spectrum, MVC, VCA, Delta-Variance, Wavelets, SCF).

The beam size is typically expressed as the full-width-half-max (FWHM). However, it is important to note that the data will still be correlated beyond the FWHM. For example, consider a randomly-drawn image with a specified power-law index:

>>> import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

>>> from turbustat.simulator import make_extended

>>> from turbustat.io.sim_tools import create_fits_hdu

>>> from astropy import units as u

>>> # Image drawn from red-noise

>>> rnoise_img = make_extended(256, powerlaw=3.)

>>> # Define properties to generate WCS information

>>> pixel_scale = 3 * u.arcsec

>>> beamfwhm = 3 * u.arcsec

>>> imshape = rnoise_img.shape

>>> restfreq = 1.4 * u.GHz

>>> bunit = u.K

>>> # Create a FITS HDU

>>> plaw_hdu = create_fits_hdu(rnoise_img, pixel_scale, beamfwhm, imshape, restfreq, bunit)

>>> plt.imshow(plaw_hdu.data) # doctest: +SKIP

The power-spectrum of the image should give a slope of 3:

>>> from turbustat.statistics import PowerSpectrum

>>> pspec = PowerSpectrum(plaw_hdu)

>>> pspec.run(verbose=True, radial_pspec_kwargs={'binsize': 1.0},

... fit_kwargs={'weighted_fit': True}, fit_2D=False,

... low_cut=1. / (60 * u.pix)) # doctest: +SKIP

OLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: y R-squared: 1.000

Model: OLS Adj. R-squared: 1.000

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 8.070e+06

Date: Thu, 21 Jun 2018 Prob (F-statistic): 0.00

Time: 11:43:47 Log-Likelihood: 701.40

No. Observations: 177 AIC: -1399.

Df Residuals: 175 BIC: -1392.

Df Model: 1

Covariance Type: nonrobust

==============================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const 0.0032 0.001 3.952 0.000 0.002 0.005

x1 -2.9946 0.001 -2840.850 0.000 -2.997 -2.992

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 252.943 Durbin-Watson: 1.077

Prob(Omnibus): 0.000 Jarque-Bera (JB): 26797.433

Skew: -5.963 Prob(JB): 0.00

Kurtosis: 62.087 Cond. No. 4.55

==============================================================================

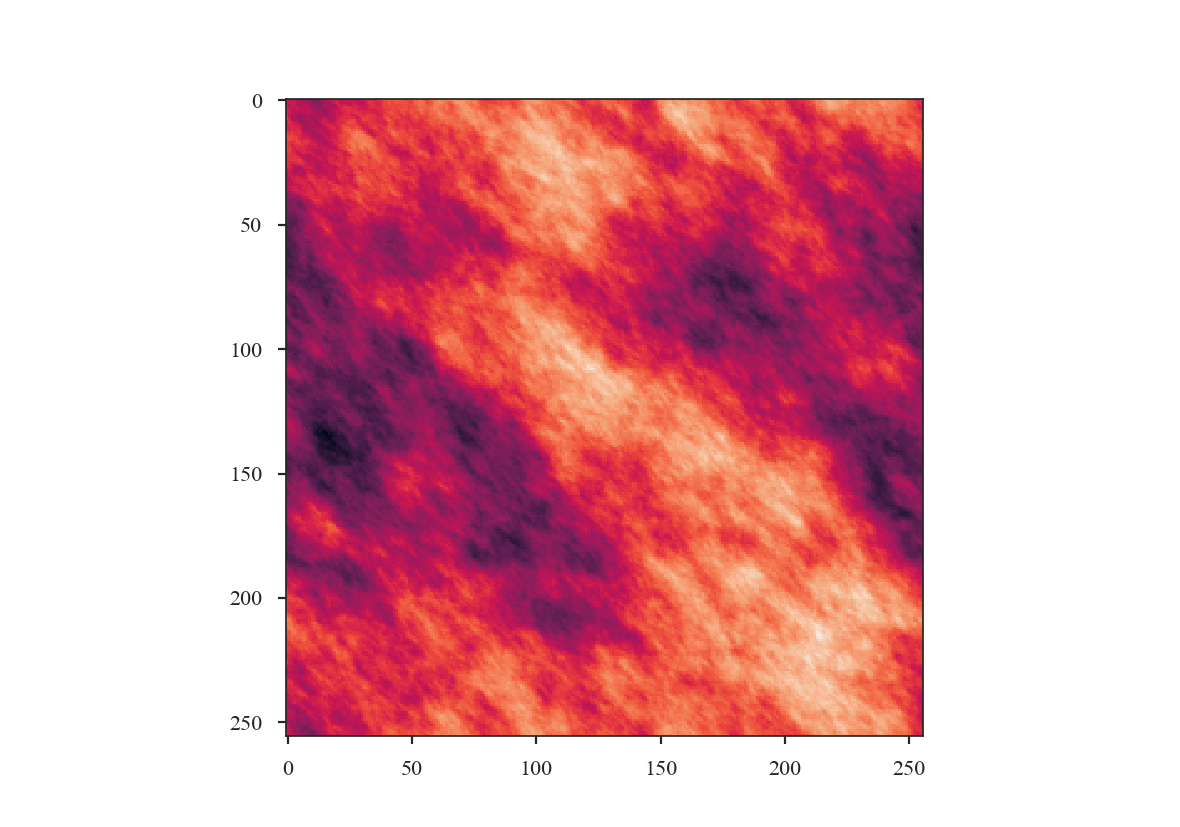

Now we will smooth this image with a Gaussian beam. The easiest way to do this is to use the built-in

tools from the spectral-cube and

radio_beam packages.

We will convert the FITS HDU to a spectral-cube Projection, and define a pencil beam for the

initial image:

>>> from spectral_cube import Projection

>>> from radio_beam import Beam

>>> pencil_beam = Beam(0 * u.deg)

>>> plaw_proj = Projection.from_hdu(plaw_hdu)

>>> plaw_proj = plaw_proj.with_beam(pencil_beam)

Next we will define the beam to smooth to. A 3-pixel wide FWHM is reasonable:

>>> new_beam = Beam(3 * plaw_hdu.header['CDELT2'] * u.deg)

>>> plaw_conv = plaw_proj.convolve_to(new_beam)

>>> plaw_conv.quicklook() # doctest: +SKIP

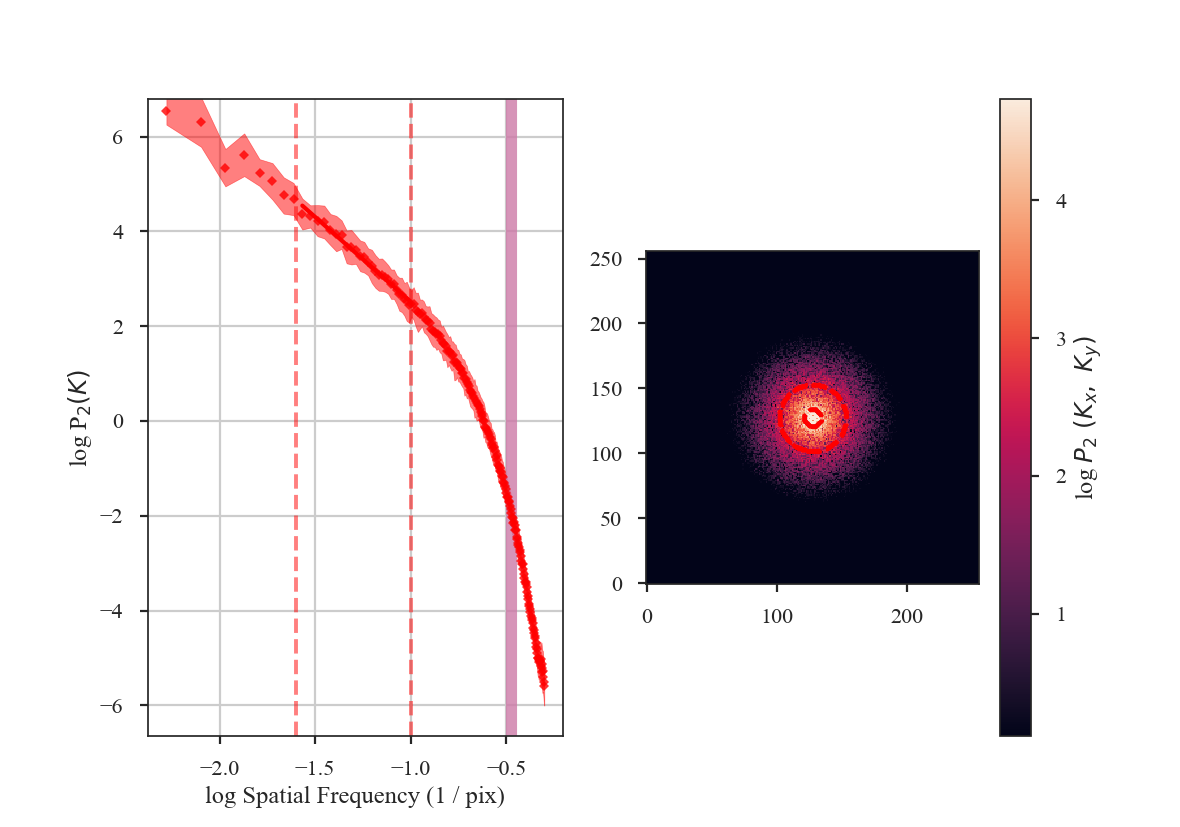

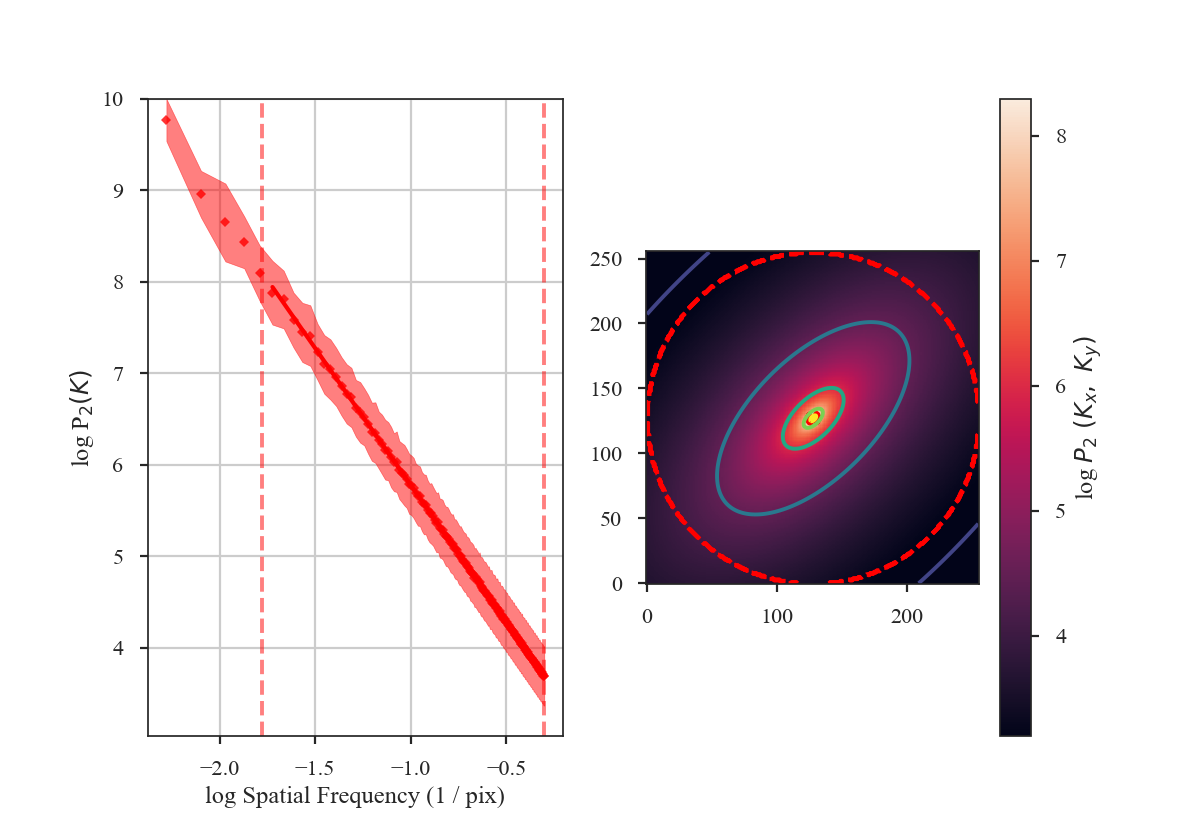

How has smoothing changed the shape of the power-spectrum?

>>> # Change the colours and comment these lines if you don't use seaborn

>>> import seaborn as sb # doctest: +SKIP

>>> col_pal = sb.color_palette() # doctest: +SKIP

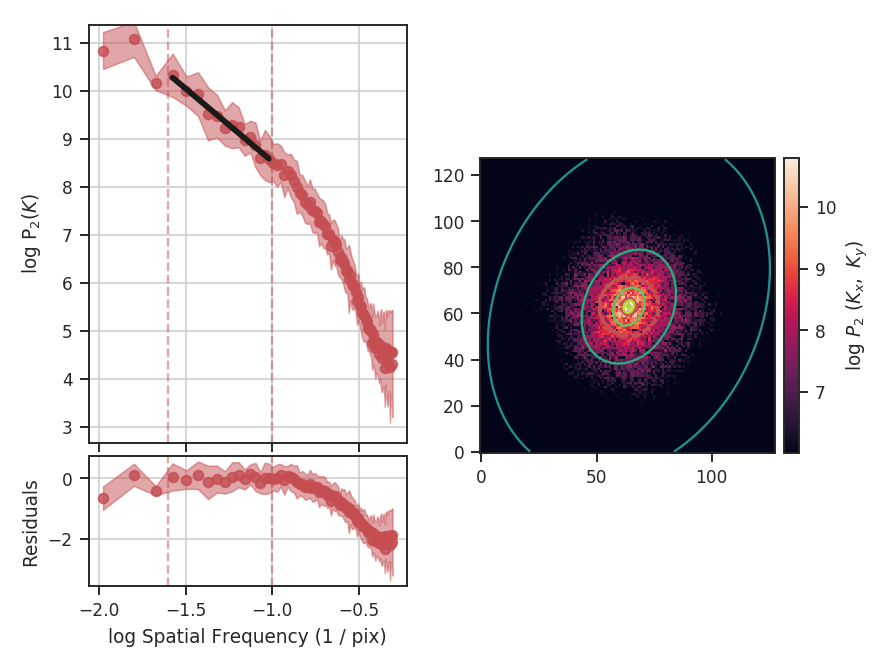

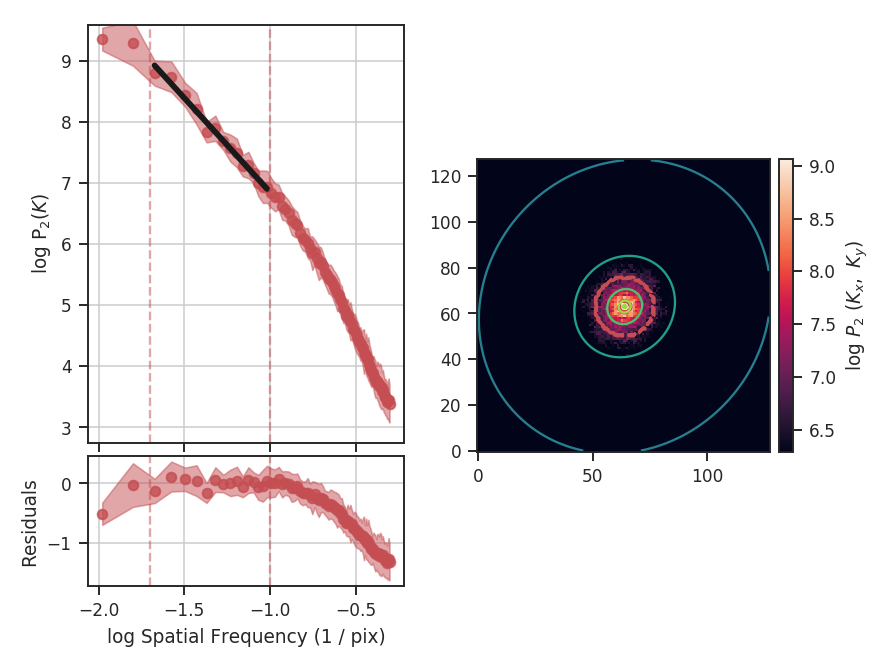

>>> pspec2 = PowerSpectrum(plaw_conv)

>>> pspec2.run(verbose=True, xunit=u.pix**-1, fit_2D=False,

... low_cut=0.025 / u.pix, high_cut=0.1 / u.pix,

... radial_pspec_kwargs={'binsize': 1.0},

... apodize_kernel='tukey') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.axvline(np.log10(1 / 3.), color=col_pal[3], linewidth=8, alpha=0.8,

... zorder=1) # doctest: +SKIP

OLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: y R-squared: 0.988

Model: OLS Adj. R-squared: 0.988

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 2059.

Date: Thu, 21 Jun 2018 Prob (F-statistic): 1.54e-25

Time: 14:23:19 Log-Likelihood: 35.997

No. Observations: 27 AIC: -67.99

Df Residuals: 25 BIC: -65.40

Df Model: 1

Covariance Type: nonrobust

==============================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const -1.0626 0.098 -10.848 0.000 -1.264 -0.861

x1 -3.5767 0.079 -45.378 0.000 -3.739 -3.414

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 3.417 Durbin-Watson: 0.840

Prob(Omnibus): 0.181 Jarque-Bera (JB): 2.072

Skew: -0.650 Prob(JB): 0.355

Kurtosis: 3.391 Cond. No. 15.7

==============================================================================

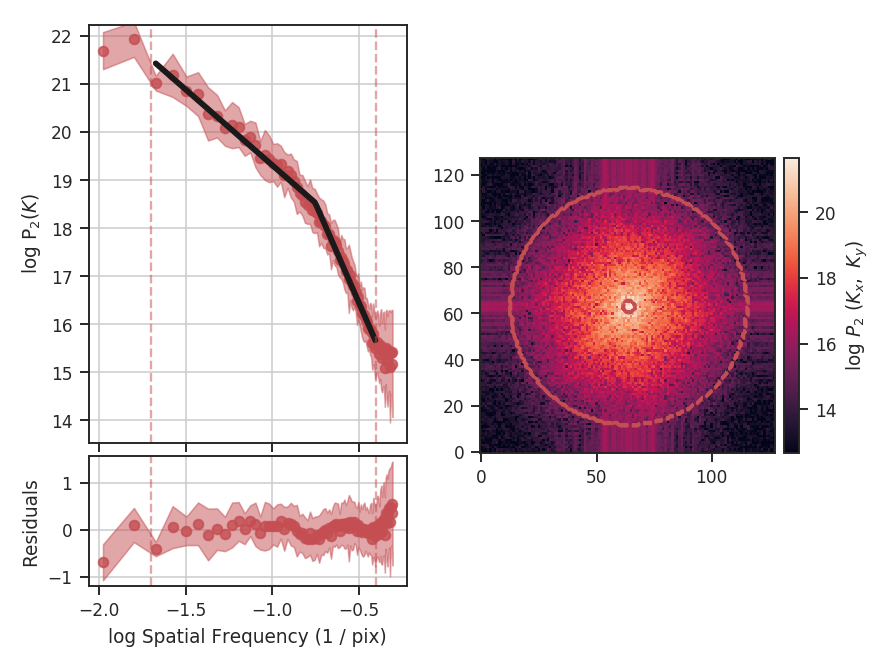

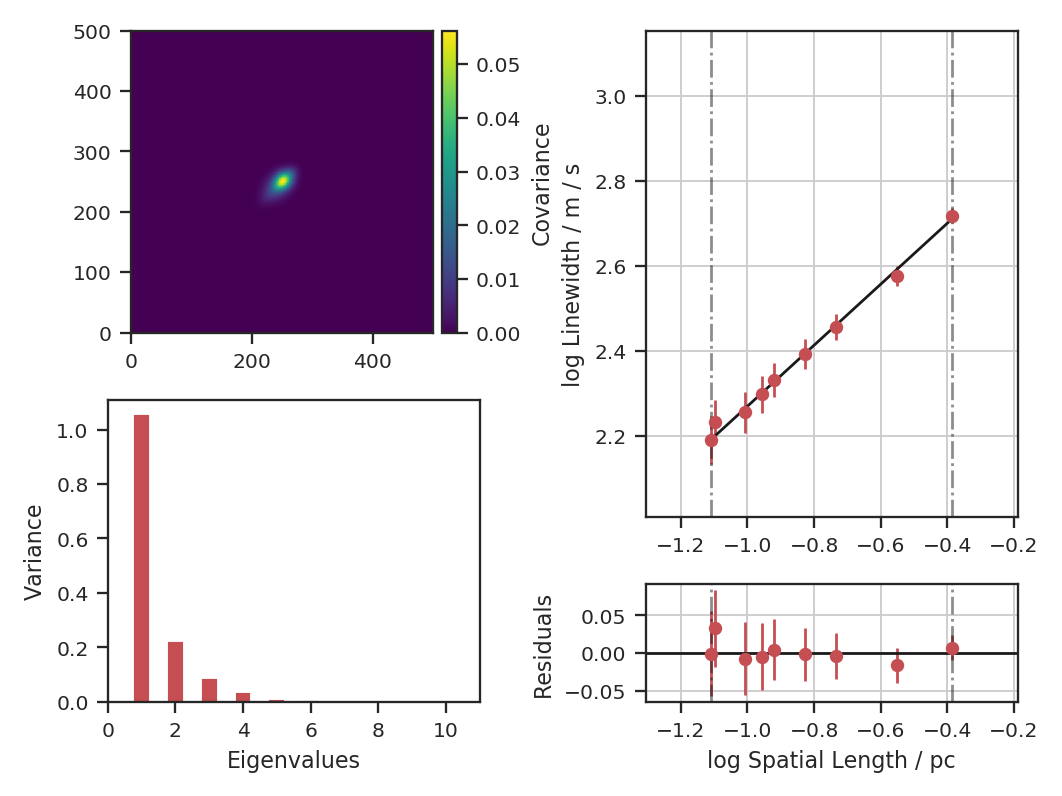

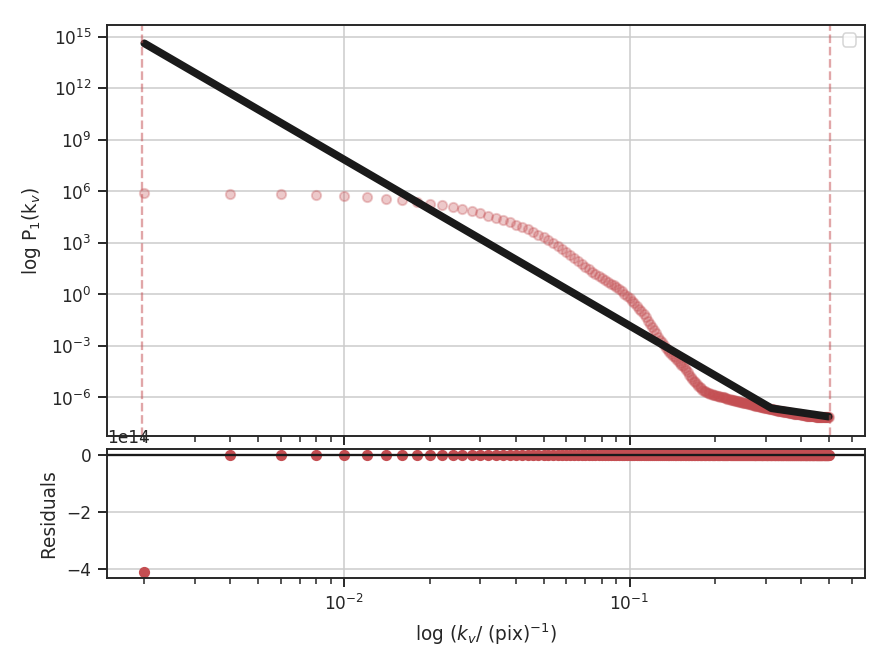

The slope of the power-spectrum is significantly steepened on small scales by the beam (see the reported result in variable x1 above).

And this steepening occurs on scales much larger than the beam FWHM, which is indicated by

the thick purple vertical line in the left-hand side of the plot. The fitting was restricted to scales much larger than three times the beam width. However, the recovered slope is still steeper than the original -3.

Also note that convolving the image with the beam causes some tapering at the edges of the image, breaking the periodicity at the edges. The image was apodized with a Tukey window, which causes some of the deviations at large scales (small frequencies). See the tutorial page on apodizing kernels for more.

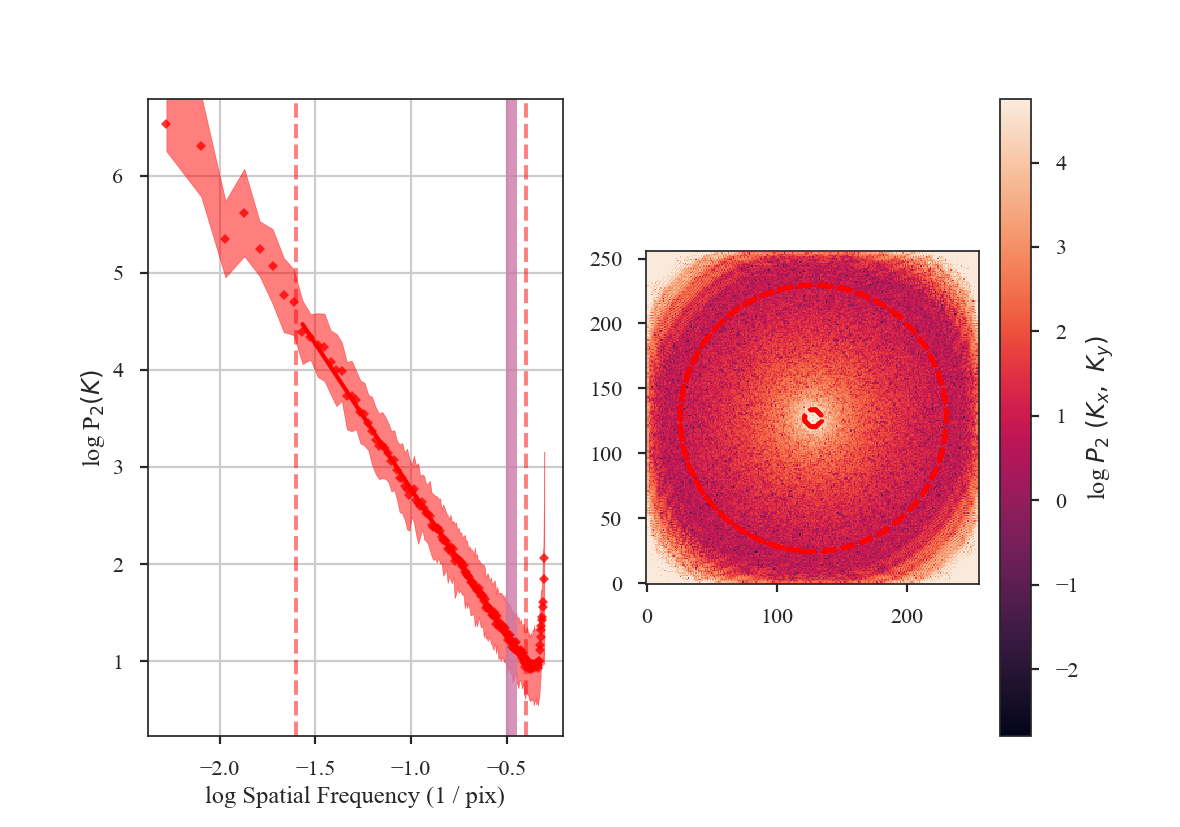

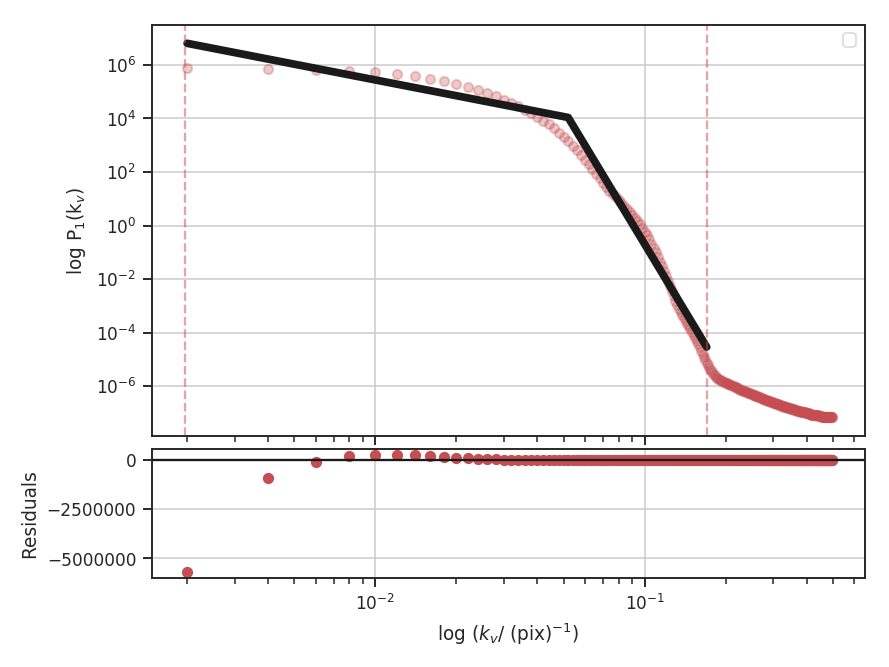

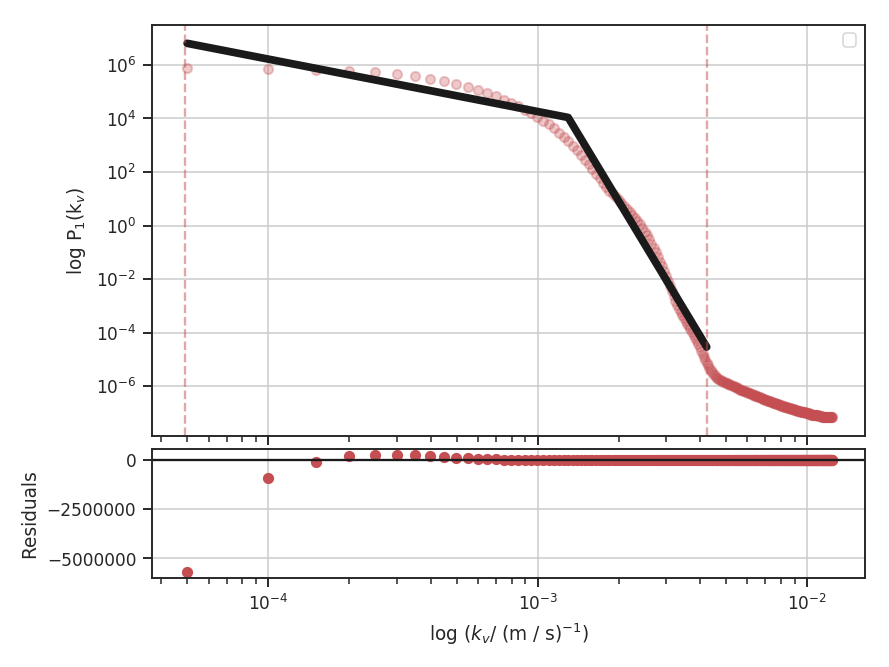

The beam size must be corrected for in the image prior to fitting the power-spectrum. This can be done by (1) including a Gaussian beam component in the model used to fit the power-spectrum, or (2) divide the power-spectrum of the image by the power-spectrum of the beam response. The former requires using a non-linear model, and is not currently implemented in TurbuStat (see Martin et al. 2015 for an example). The latter method can be applied prior to fitting, allowing a linear model to still be used for fitting.

The beam correction in TurbuStat requires the optional package radio_beam to be installed. radio_beam allows the beam response for any 2D elliptical Gaussian to be returned. For statistics that create a power-spectrum (Spatial Power-Spectrum, VCA, MVC), the beam correction can be applied by specifying beam_correct=True:

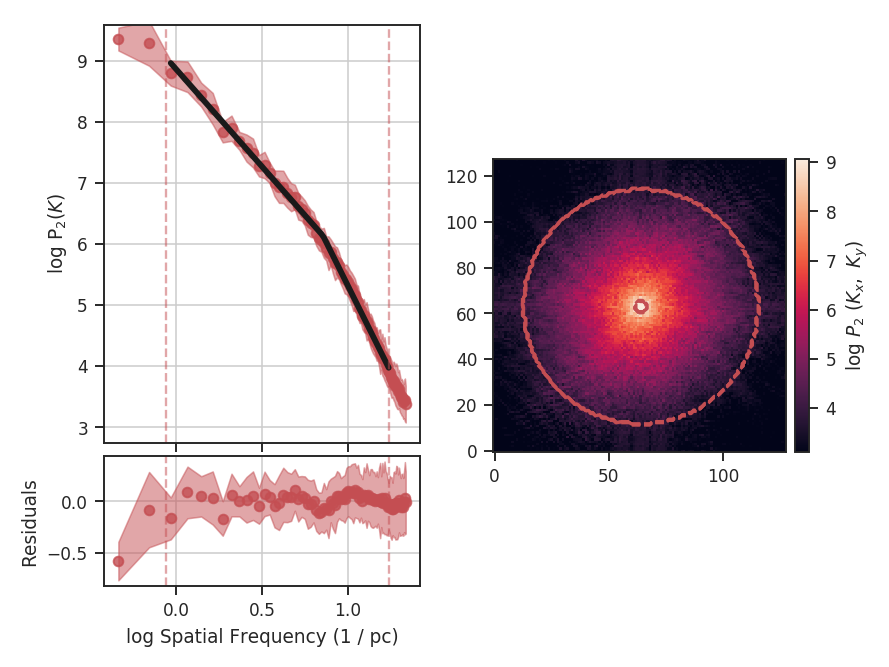

>>> pspec3 = PowerSpectrum(plaw_conv)

>>> pspec3.run(verbose=True, xunit=u.pix**-1, fit_2D=False,

... low_cut=0.025 / u.pix, high_cut=0.4 / u.pix,

... apodize_kernel='tukey', beam_correct=True) # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.axvline(np.log10(1 / 3.), color=col_pal[3], linewidth=8, alpha=0.8,

... zorder=1) # doctest: +SKIP

OLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: y R-squared: 0.998

Model: OLS Adj. R-squared: 0.998

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 8.828e+04

Date: Thu, 21 Jun 2018 Prob (F-statistic): 5.55e-192

Time: 14:38:33 Log-Likelihood: 268.87

No. Observations: 137 AIC: -533.7

Df Residuals: 135 BIC: -527.9

Df Model: 1

Covariance Type: nonrobust

==============================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const -0.2247 0.008 -27.671 0.000 -0.241 -0.209

x1 -2.9961 0.010 -297.116 0.000 -3.016 -2.976

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 7.089 Durbin-Watson: 1.500

Prob(Omnibus): 0.029 Jarque-Bera (JB): 9.274

Skew: 0.285 Prob(JB): 0.00969

Kurtosis: 4.140 Cond. No. 5.50

==============================================================================

The shape of the power-spectrum has been restored and we recover the correct slope. The deviation on small scales (large frequencies) occurs on scales smaller than about the FWHM of the beam where the information has been lost by the spatial smoothing applied to the image. If the beam is over-sampled by a larger factor — say with a 6-pixel FWHM instead of 3 — the increase in power on small scales will affect a larger region of the power-spectrum. This region should be excluded from the power-spectrum fit. A reasonable lower-limit to fit the power-spectrum to is the FWHM of the beam. Additional noise in the image will tend to flatten the power-spectrum to larger scales, so setting the lower fitting limit to a couple times the beam width may be necessary. We recommend visually examining the quality of the fit.

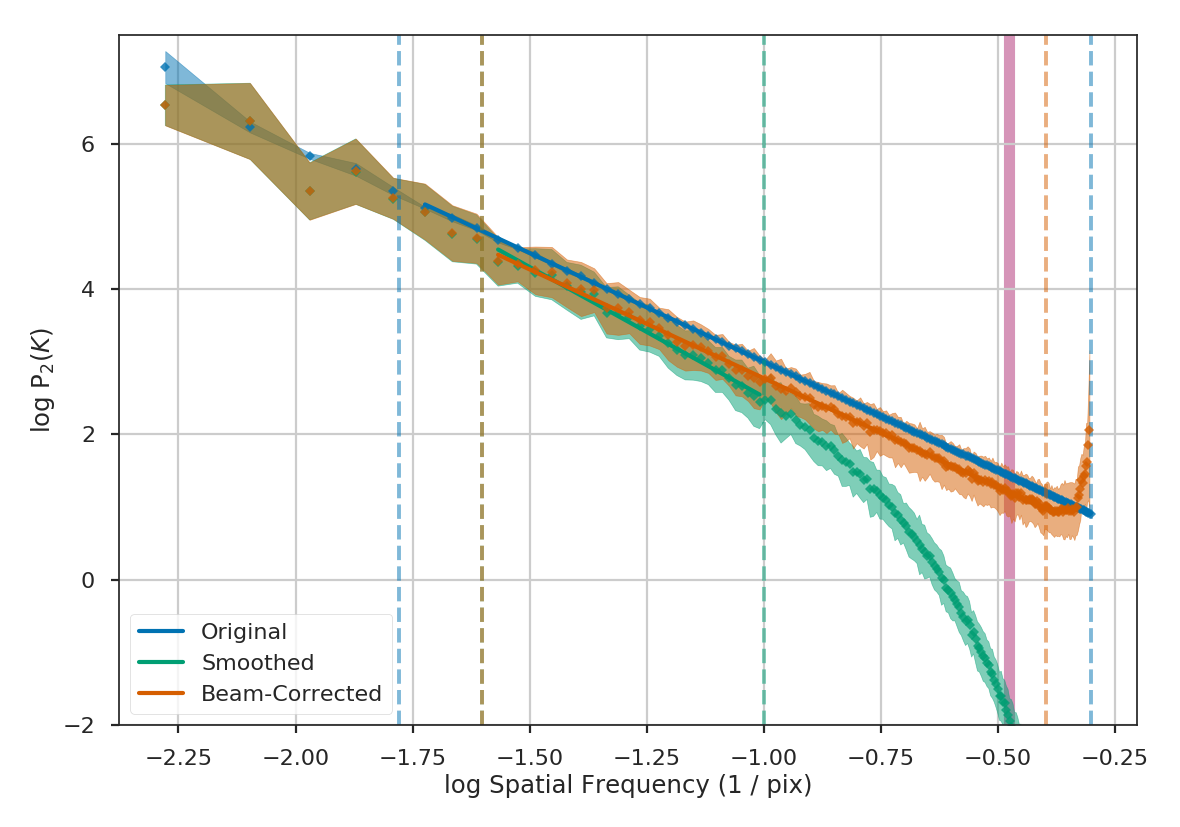

Here are the three power-spectra shown above overplotted to highlight the shape changes from spatial smoothing:

>>> pspec.plot_fit(color=col_pal[0], label='Original') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> pspec2.plot_fit(color=col_pal[1], label='Smoothed') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> pspec3.plot_fit(color=col_pal[2], label='Beam-Corrected') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.legend(frameon=True, loc='lower left') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.axvline(np.log10(1 / 3.), color=col_pal[3], linewidth=8, alpha=0.8, zorder=-1) # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.ylim([-2, 7.5]) # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.tight_layout() # doctest: +SKIP

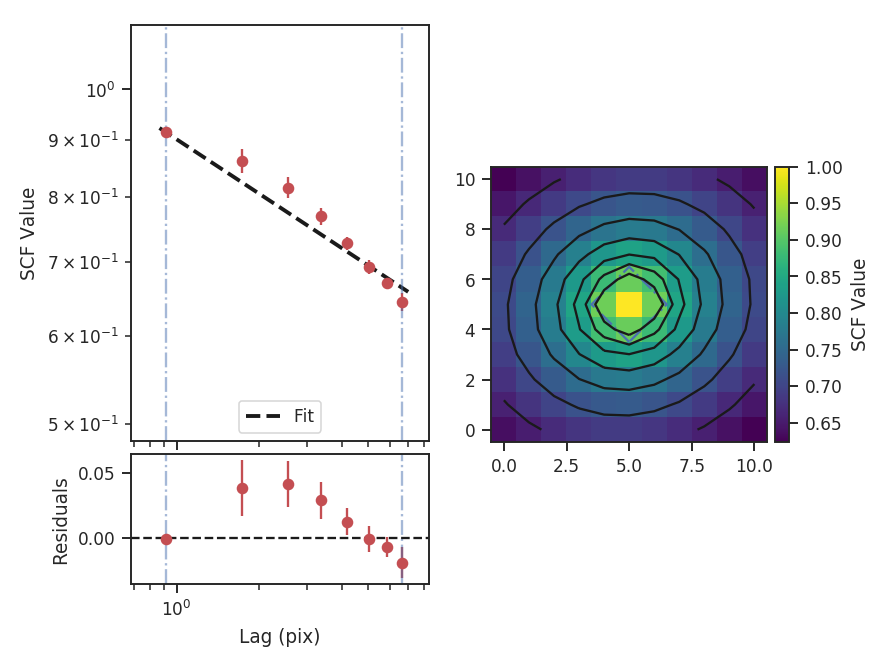

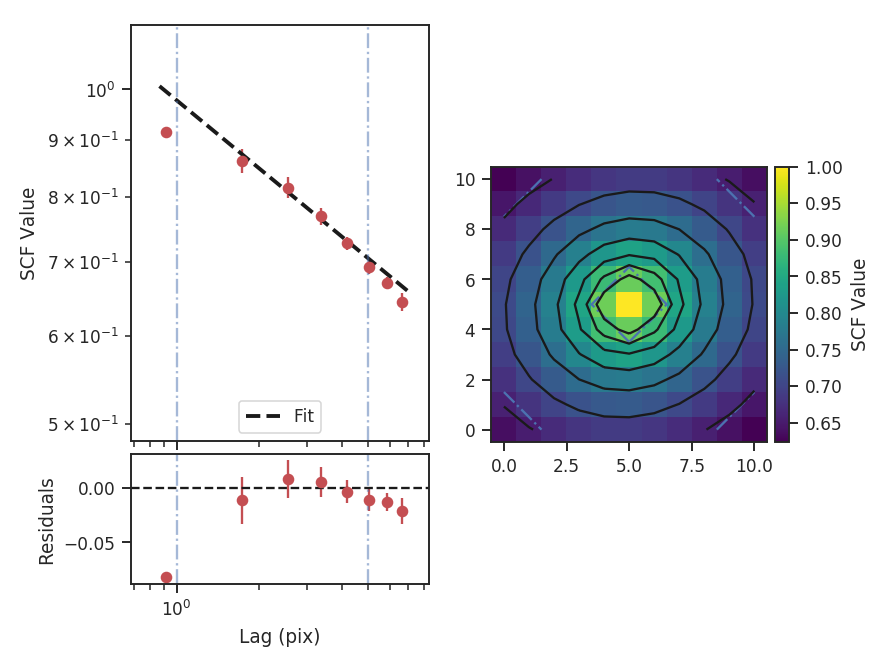

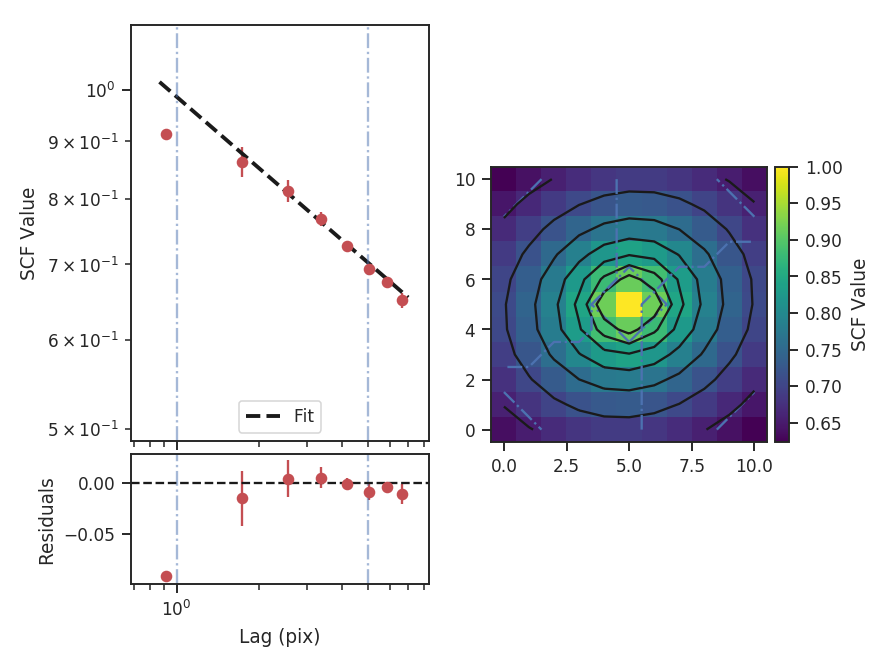

Similar fitting restrictions apply to the MVC and VCA, as well. The beam correction can be applied in the same manner as described above. For other spatial methods which do not use the power-spectrum, the scales of the beam should at least be excluded from any fitting. For example, lag scales smaller than the beam in the Delta-Variance, Wavelets, and SCF should not be fit. The spatial filtering used to measure Statistical Moments should be set to a width of at least the beam size.

Dealing with missing data¶

When running any statistic in TurbuStat on data set with noise, there is a question of whether or not to mask out noisy data. Masking noisy data is a common practice with observational data and is often crucial for recovering scientifically-usable results. However, some of the statistics in TurbuStat implicitly assume the map is continuous. This page demonstrates the pros and cons of masking data versus including noisy regions.

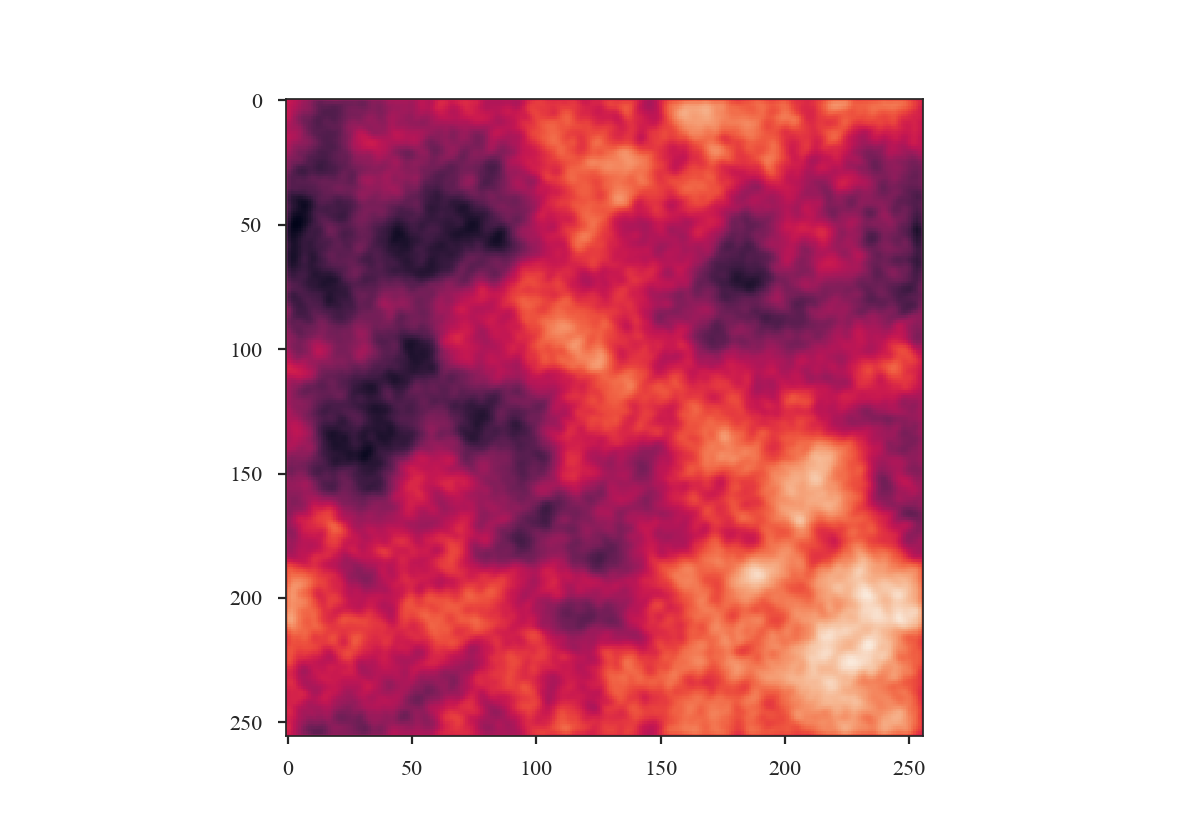

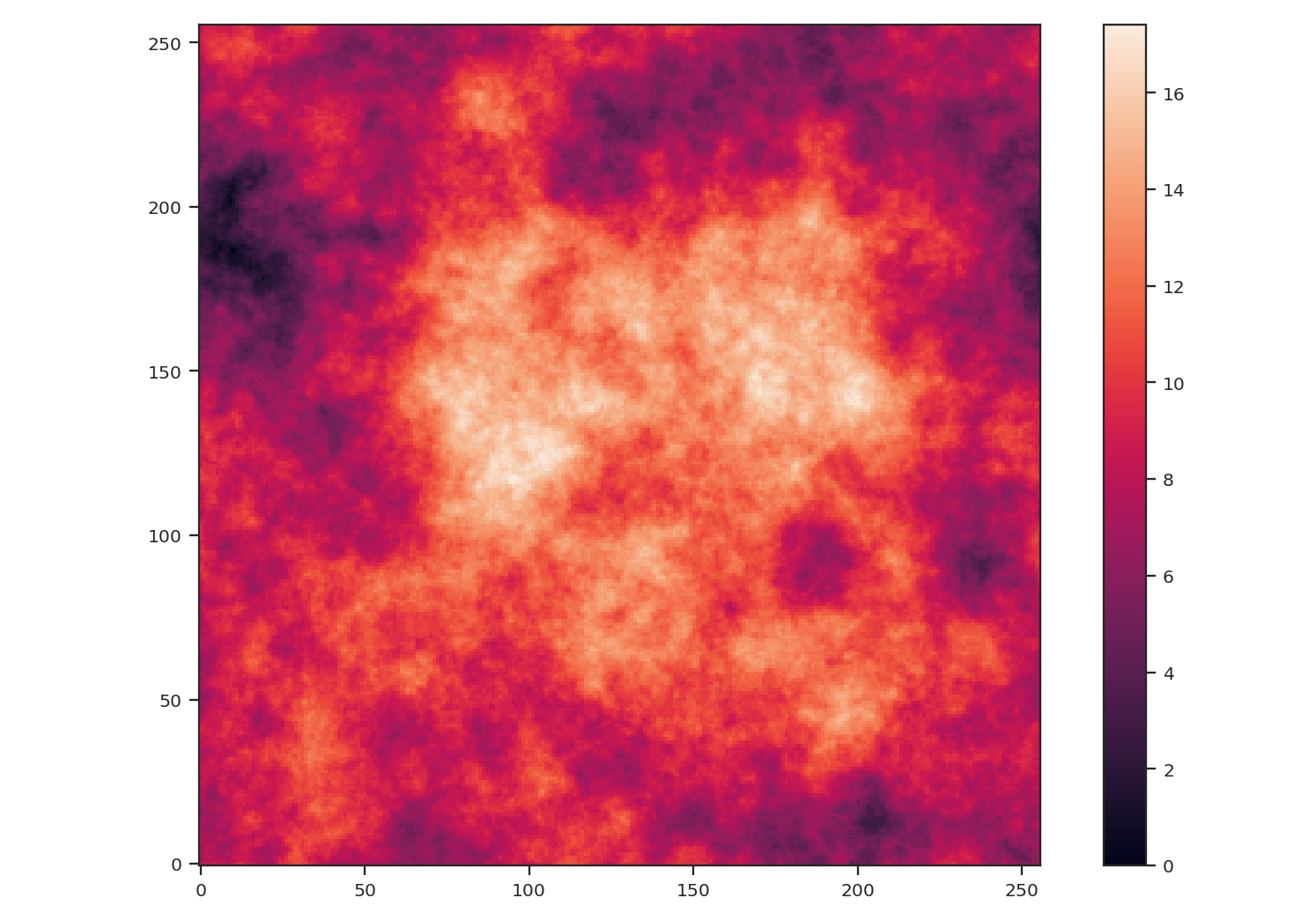

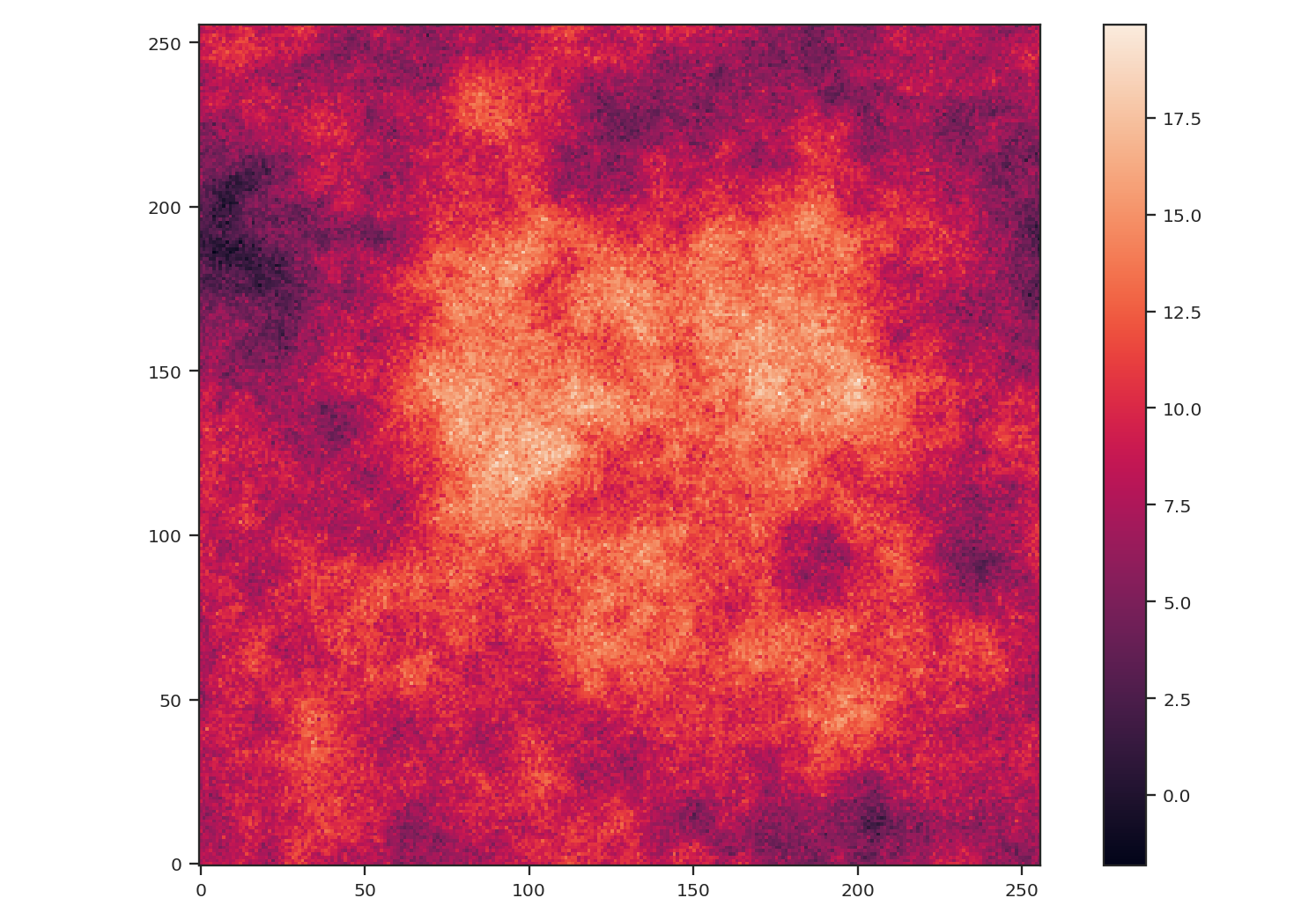

We will create a red noise image to use as an example:

>>> import numpy as np

>>> import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

>>> from turbustat.simulator import make_extended

>>> img = make_extended(256, powerlaw=3., randomseed=54398493)

>>> # Now shuffle so the peak is near the centre

>>> img = np.roll(img, (128, -30), (0, 1))

>>> img -= img.min()

>>> plt.imshow(img, origin='lower')

>>> plt.colorbar()

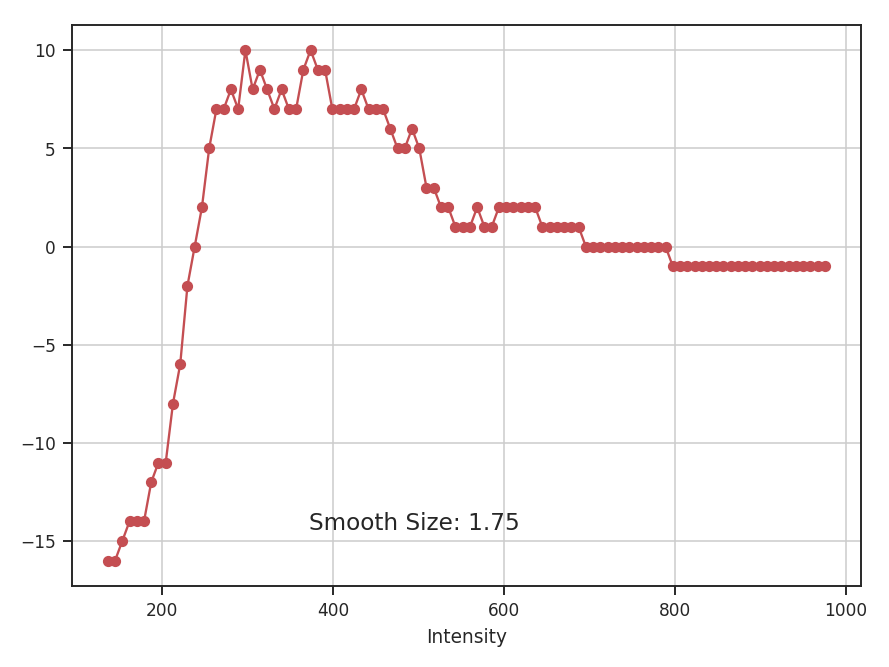

After creating the image, we centered the peak of the map to be near the centre. We also subtracted the minimum value from the image to remove negative values to better mimic observational data.

We will compare the effect of noise and masking on two statistics: the PowerSpectrum and the Delta-variance. The power-spectrum relies on a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), which implicitly assumes that the map edges are periodic. This assumption presents an issue for observational maps with emission at their edge and requires an apodizing kernel to be applied to the data prior to computing the power-spectrum. The delta-variance relies on convolving the map by a set of kernels with increasing size. While the convolution also uses a Fourier transform, noisy or missing regions in the data are down-weighted so this method can be used on observational data with arbitrary shape (Ossenkopf at al. 2008a).

Note

Throughout this example, we will not create realistic WCS information for the image because we will be altering the image in each step. For brevity, we pass fits.PrimaryHDU(img) which creates a FITS HDU without complete WCS information. For a tutorial on how TurbuStat creates mock WCS information, see here.

First, we will use both statistics on the unaltered image:

>>> from astropy.io import fits

>>> from turbustat.statistics import PowerSpectrum, DeltaVariance

>>> pspec = PowerSpectrum(fits.PrimaryHDU(img))

>>> pspec.run(verbose=True)

OLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: y R-squared: 1.000

Model: OLS Adj. R-squared: 1.000

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 3.239e+05

Date: Thu, 14 Feb 2019 Prob (F-statistic): 1.61e-293

Time: 17:08:19 Log-Likelihood: 610.32

No. Observations: 181 AIC: -1217.

Df Residuals: 179 BIC: -1210.

Df Model: 1

Covariance Type: HC3

==============================================================================

coef std err z P>|z| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const 2.3594 0.003 755.971 0.000 2.353 2.366

x1 -2.9893 0.005 -569.096 0.000 -3.000 -2.979

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 150.694 Durbin-Watson: 1.634

Prob(Omnibus): 0.000 Jarque-Bera (JB): 5853.912

Skew: -2.593 Prob(JB): 0.00

Kurtosis: 30.374 Cond. No. 4.15

==============================================================================

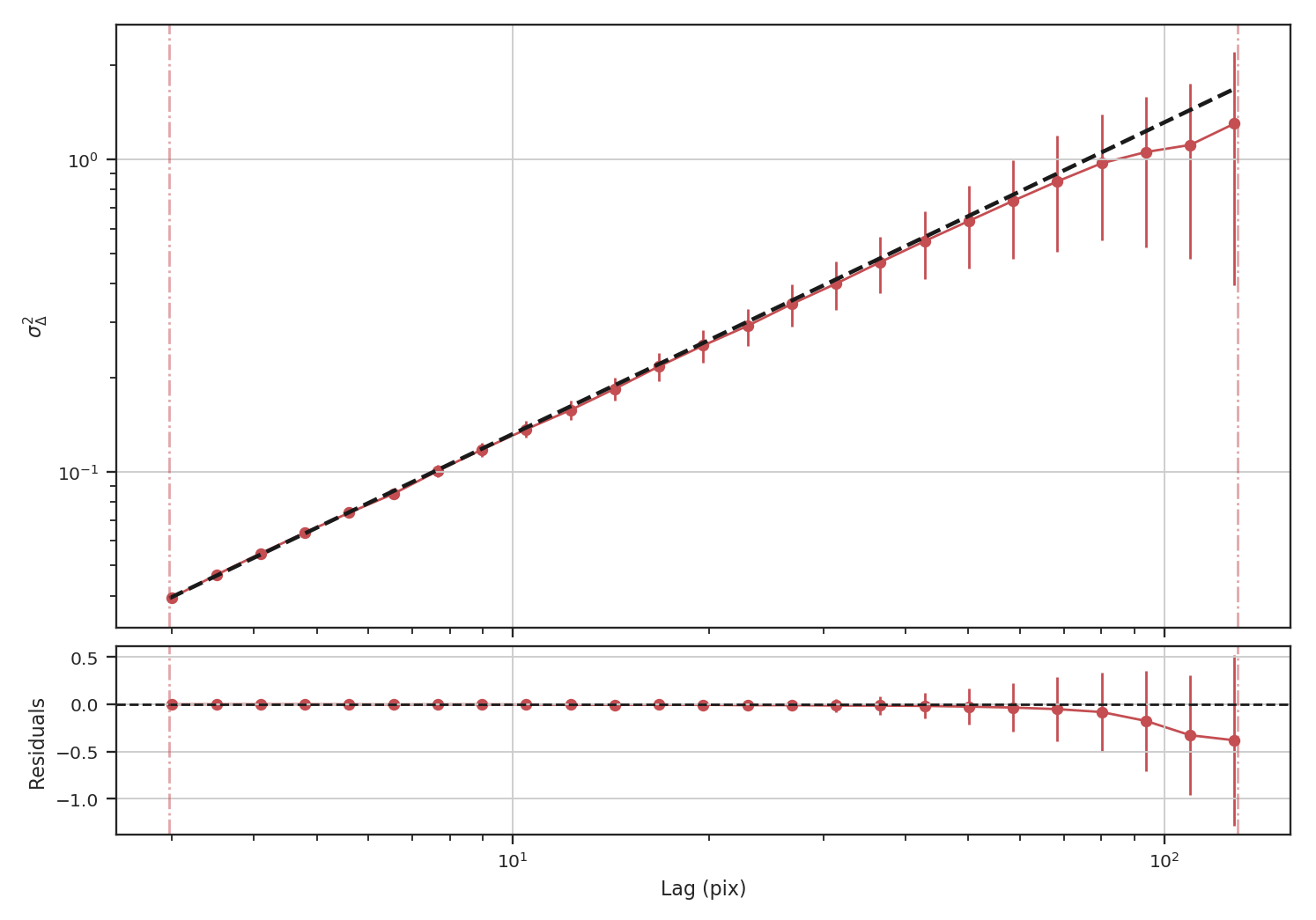

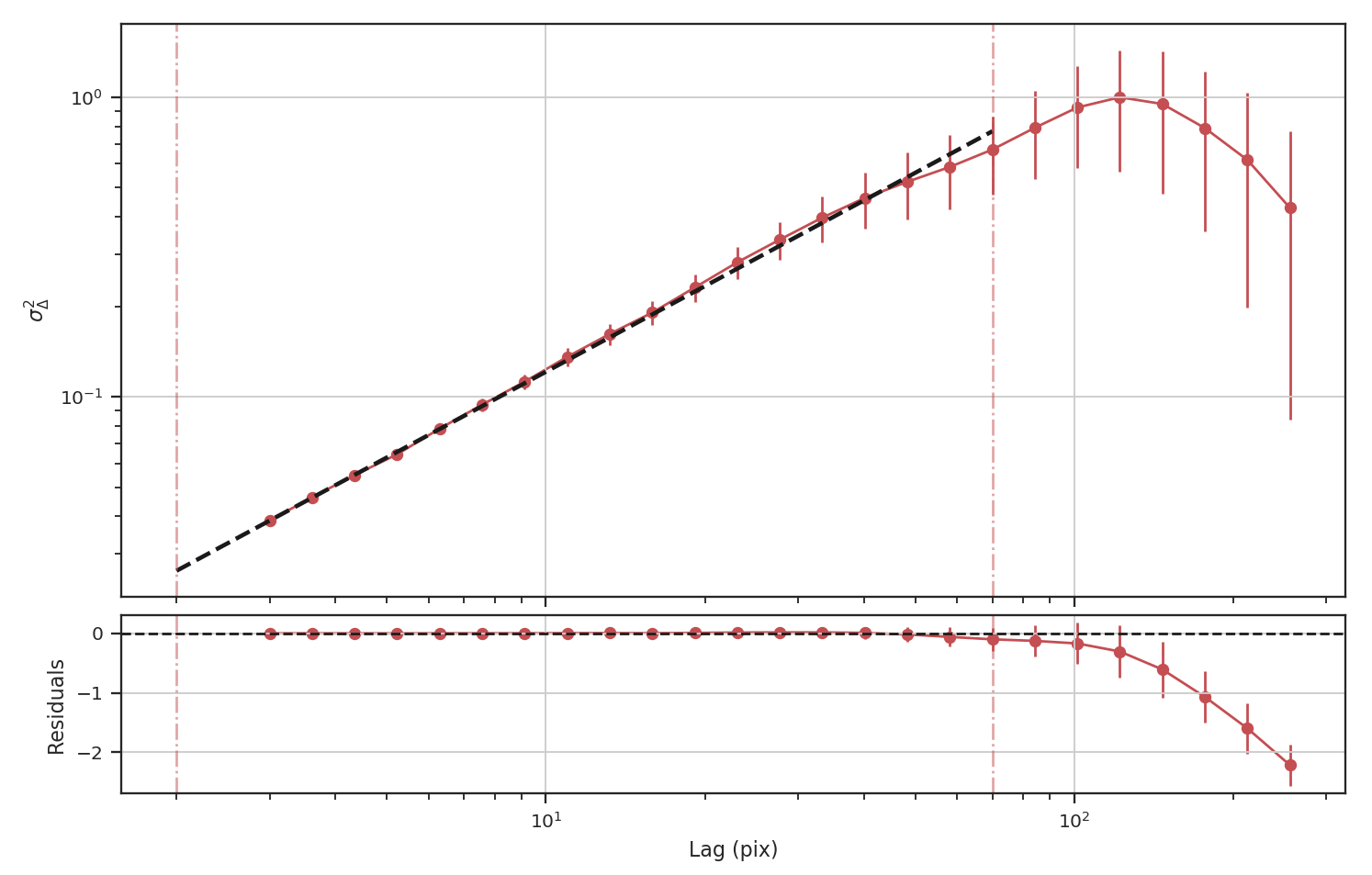

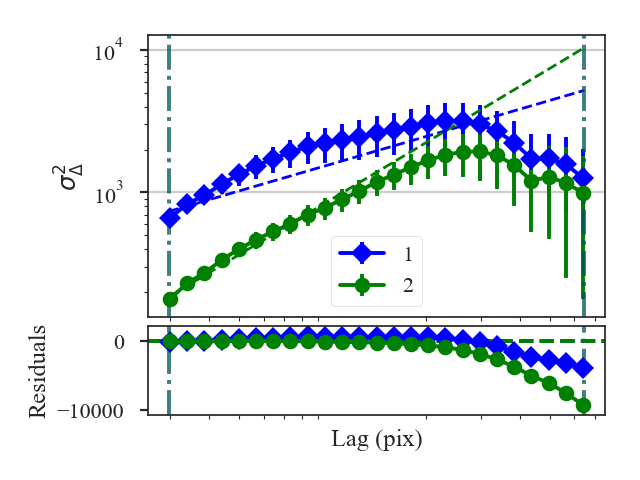

The power-spectrum recovers the expected slope of \(-3\). The delta-variance slope should be \(-\beta -2\), where \(\beta\) is the power-spectrum slope, so we should find a slope of \(1\):

>>> delvar = DeltaVariance(fits.PrimaryHDU(img))

>>> delvar.run(verbose=True)

WLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: y R-squared: 0.999

Model: WLS Adj. R-squared: 0.999

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 1741.

Date: Thu, 14 Feb 2019 Prob (F-statistic): 3.50e-23

Time: 17:13:16 Log-Likelihood: 48.412

No. Observations: 25 AIC: -92.82

Df Residuals: 23 BIC: -90.39

Df Model: 1

Covariance Type: HC3

==============================================================================

coef std err z P>|z| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const -1.8780 0.017 -113.441 0.000 -1.910 -1.846

x1 0.9986 0.024 41.723 0.000 0.952 1.046

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 6.913 Durbin-Watson: 1.306

Prob(Omnibus): 0.032 Jarque-Bera (JB): 6.334

Skew: 0.535 Prob(JB): 0.0421

Kurtosis: 5.221 Cond. No. 12.1

==============================================================================

Indeed, we recover the correct slope from the delta-variance.

To demonstrate how masking affects each of these statistics, we will arbitrarily mask low values below the 25 percentile in the example image and run each statistic:

>>> masked_img = img.copy()

>>> masked_img[masked_img < np.percentile(img, 25)] = np.NaN

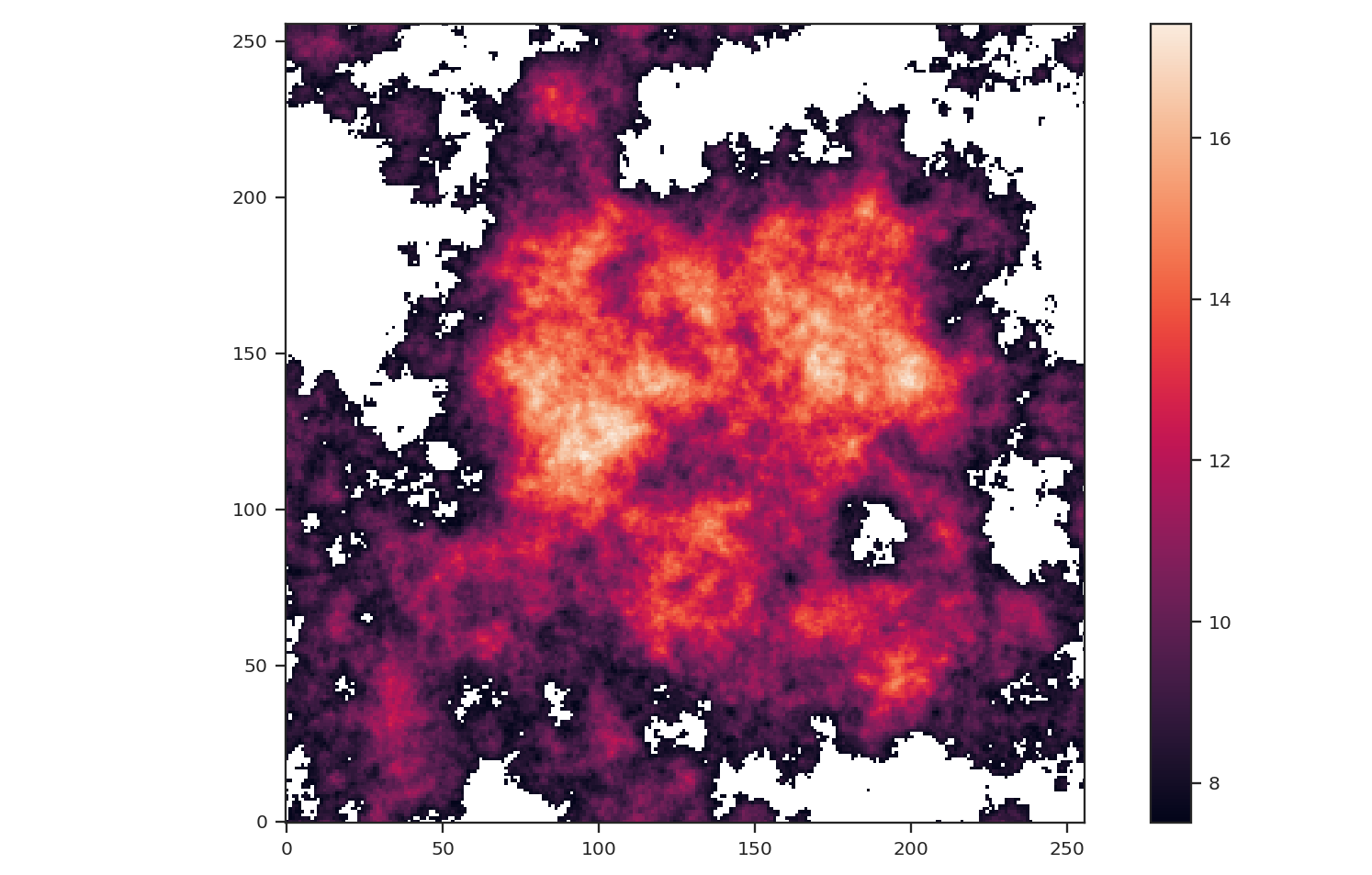

>>> plt.imshow(masked_img, origin='lower')

>>> plt.colorbar()

The central bright region remains but much of the fainter features around the image edges have been masked.:

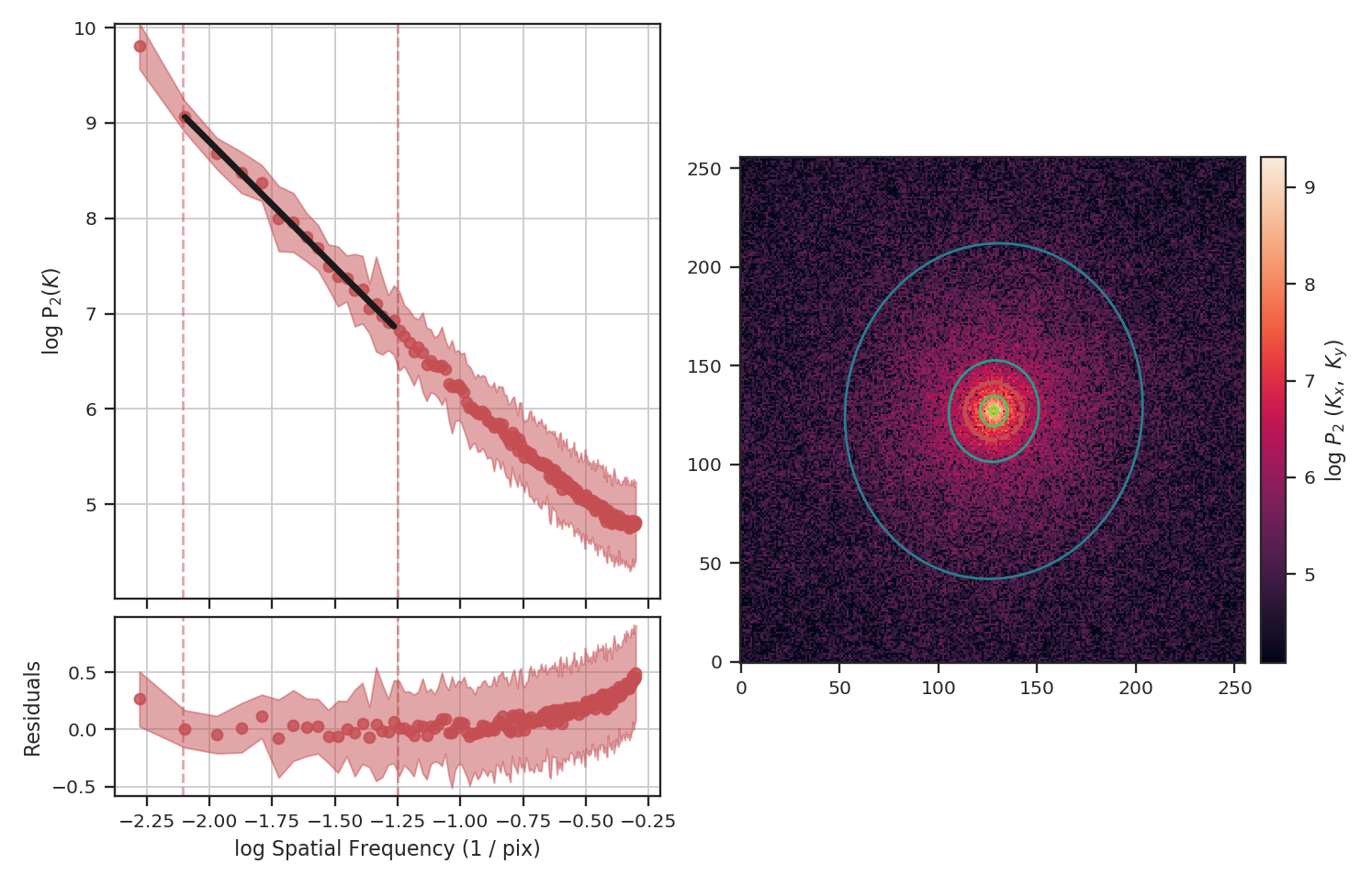

>>> pspec_masked = PowerSpectrum(fits.PrimaryHDU(masked_img))

>>> pspec_masked.run(verbose=True, high_cut=10**-1.25 / u.pix)

OLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: y R-squared: 0.993

Model: OLS Adj. R-squared: 0.993

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 2636.

Date: Thu, 14 Feb 2019 Prob (F-statistic): 3.45e-19

Time: 17:19:21 Log-Likelihood: 27.859

No. Observations: 18 AIC: -51.72

Df Residuals: 16 BIC: -49.94

Df Model: 1

Covariance Type: HC3

==============================================================================

coef std err z P>|z| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const 3.5321 0.080 44.347 0.000 3.376 3.688

x1 -2.6362 0.051 -51.344 0.000 -2.737 -2.536

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 0.336 Durbin-Watson: 2.692

Prob(Omnibus): 0.845 Jarque-Bera (JB): 0.445

Skew: 0.259 Prob(JB): 0.800

Kurtosis: 2.429 Cond. No. 14.6

==============================================================================

Masking has significantly flattened the power-spectrum, even with the restriction we added to fit only scales larger than \(10^{1.25}\sim18\) pixels. In fact, flattening the power-spectrum is similar to how noise effects the power-spectrum. Why is this? FFTs cannot be used on data with missing values specified as NaNs. Instead, we have to choose a finite value to _fill_ the missing data; we typically choose to fill these regions with \(0\). When large regions are missing, the fill value leads to a large region with constant values that, by itself, would have a power-spectrum index of \(0\).

The delta-variance avoids the filling issue for masked data by introducing weights. Places with missing data have a very low weight or remained masked. The astropy convolution package has routines for interpolating over masked data, which is useful when small regions are missing data but is not typically useful when the missing data lies at the edge of emission in a map. With the masked image, the delta-variance curve we find is:

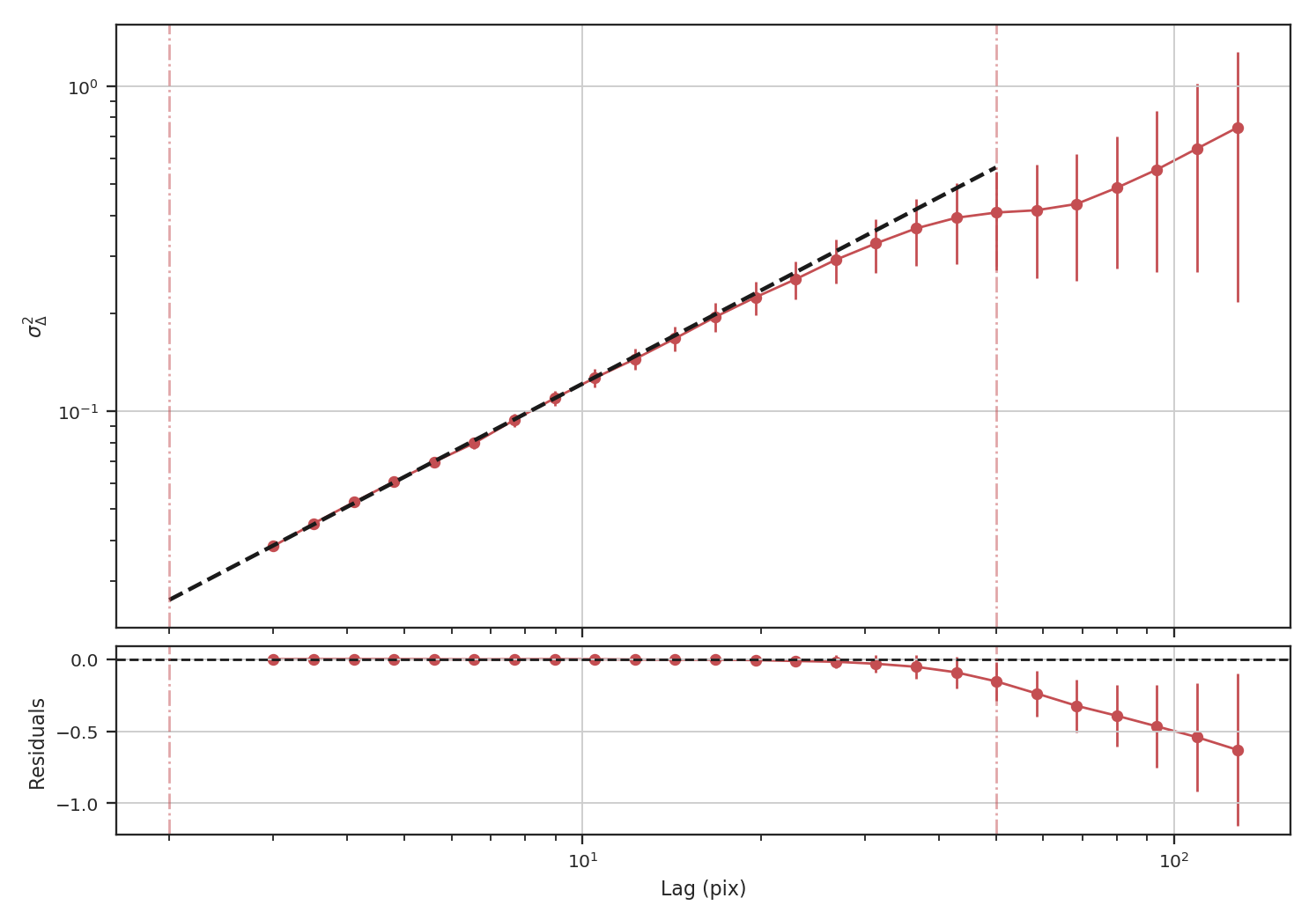

>>> delvar_masked = DeltaVariance(fits.PrimaryHDU(masked_img))

>>> delvar_masked.run(verbose=True, xlow=2 * u.pix, xhigh=50 * u.pix)

WLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: y R-squared: 0.999

Model: WLS Adj. R-squared: 0.999

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 1860.

Date: Thu, 14 Feb 2019 Prob (F-statistic): 5.52e-18

Time: 17:30:29 Log-Likelihood: 52.504

No. Observations: 18 AIC: -101.0

Df Residuals: 16 BIC: -99.23

Df Model: 1

Covariance Type: HC3

==============================================================================

coef std err z P>|z| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const -1.8679 0.015 -120.680 0.000 -1.898 -1.838

x1 0.9520 0.022 43.128 0.000 0.909 0.995

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 4.484 Durbin-Watson: 1.339

Prob(Omnibus): 0.106 Jarque-Bera (JB): 2.180

Skew: 0.694 Prob(JB): 0.336

Kurtosis: 3.991 Cond. No. 11.7

==============================================================================

When restricting the fit to scales of less than 50 pixels (about a quarter of the image), we recover a slope of \(0.95\), significantly closer to the expected value of \(1.0\) relative to the power-spectrum.

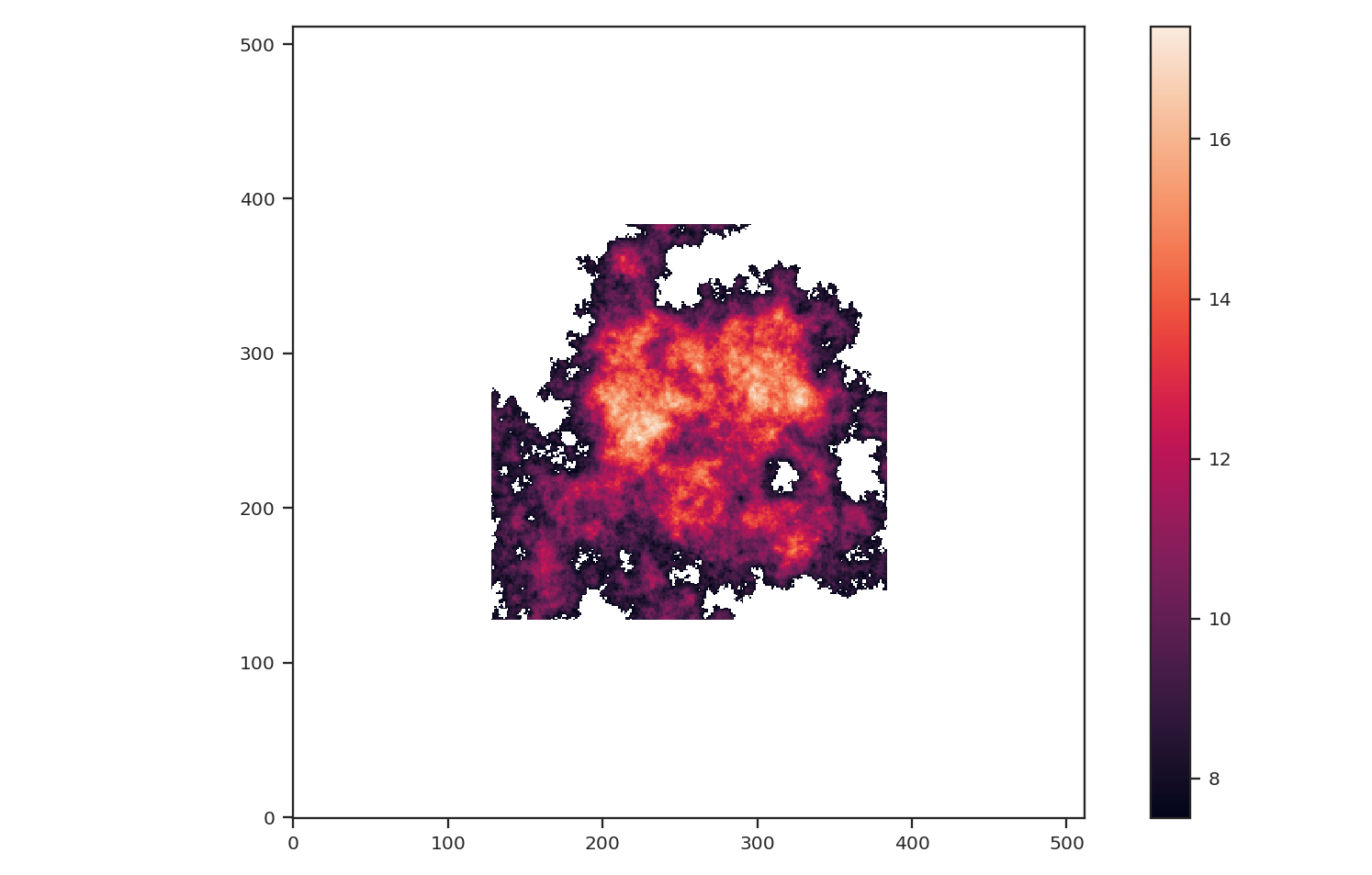

Another issue that could be encountered with observational data are large empty regions in a map, either due to masking (similar to the above example) or when we want to investigate a single object and have masked out all others. This situation could arise when the data are segmented into individual _”blobs”_ and we want to study the properties of each blob. To mimic this situation, we will pad the edges (following the numpy example) of the image with empty values as:

>>> def pad_with(vector, pad_width, iaxis, kwargs):

... pad_value = kwargs.get('padder', 0.)

... vector[:pad_width[0]] = pad_value

... vector[-pad_width[1]:] = pad_value

... return vector

>>> padded_masked_img = np.pad(masked_img, 128, pad_with, padder=np.NaN)

We are also only going to keep the biggest continuous region in the padded image to mimic studying a single object picked from a larger image:

>>> from scipy import ndimage as nd

>>> labs, num = nd.label(np.isfinite(padded_masked_img), np.ones((3, 3)))

>>> # Keep the largest region only

>>> padded_masked_img[np.where(labs > 1)] = np.NaN

>>> plt.imshow(padded_masked_img, origin='lower')

>>> plt.colorbar()

The unmasked region is now surrounded by huge empty regions. How does this affect the power-spectrum and delta-variance?:

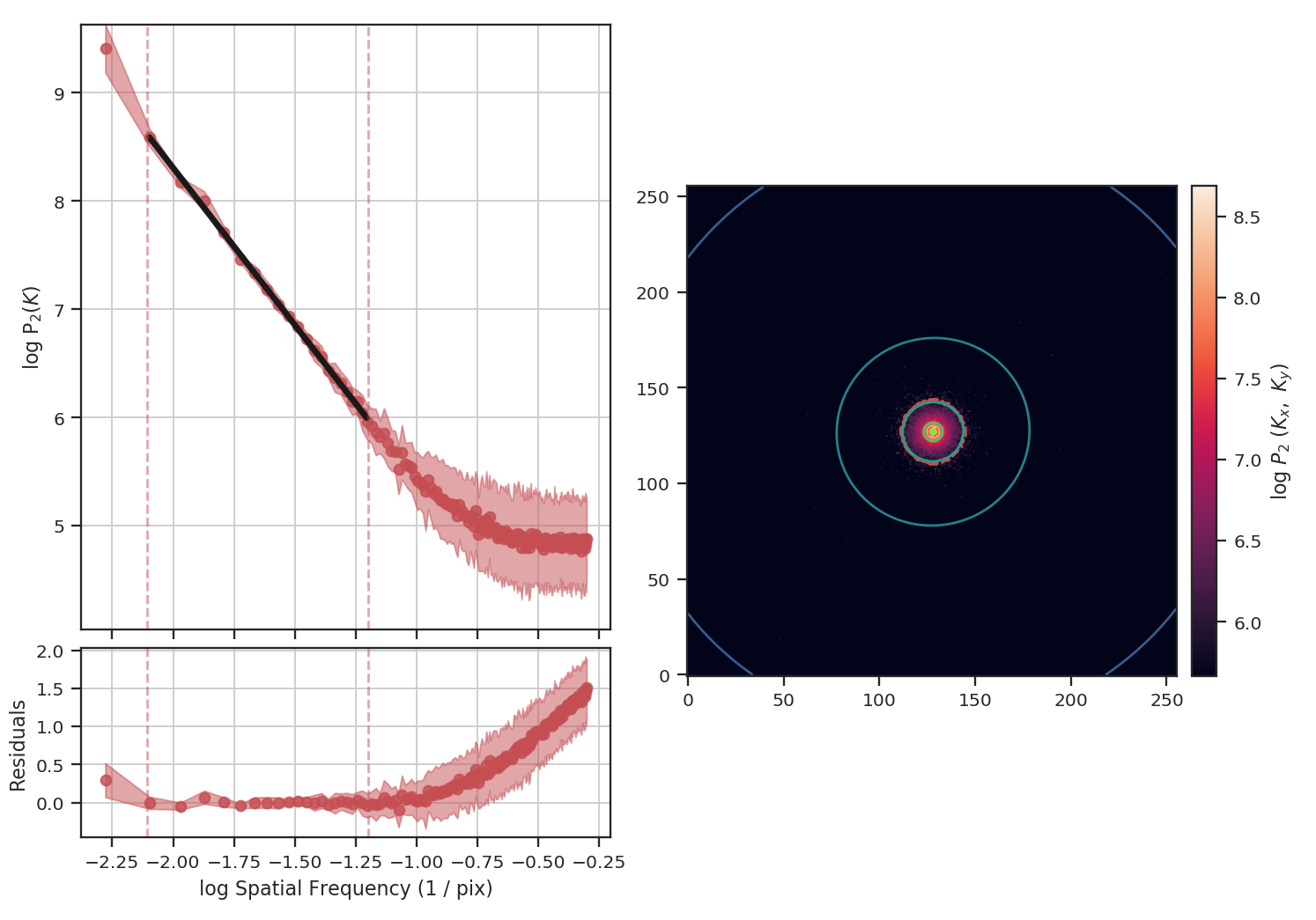

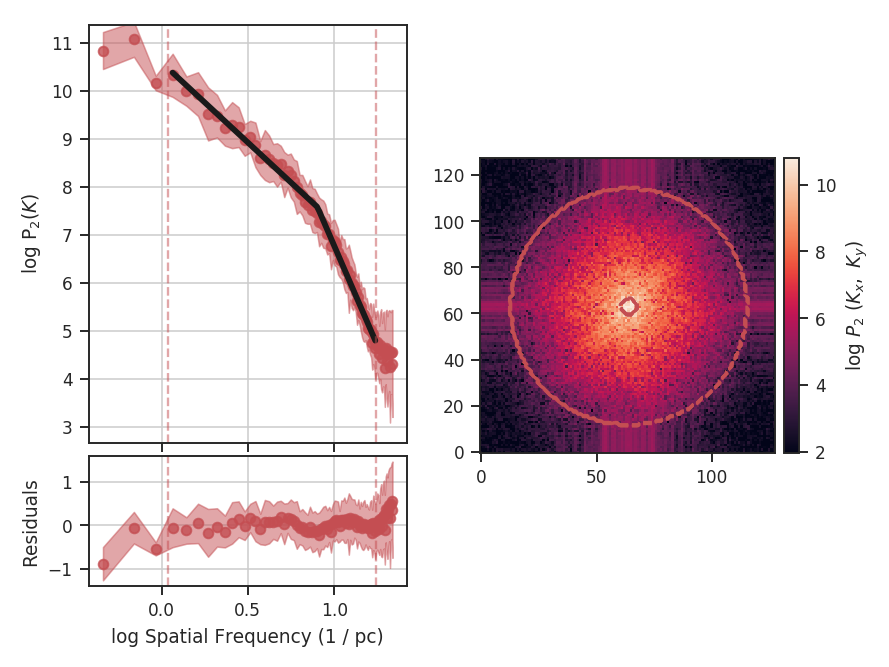

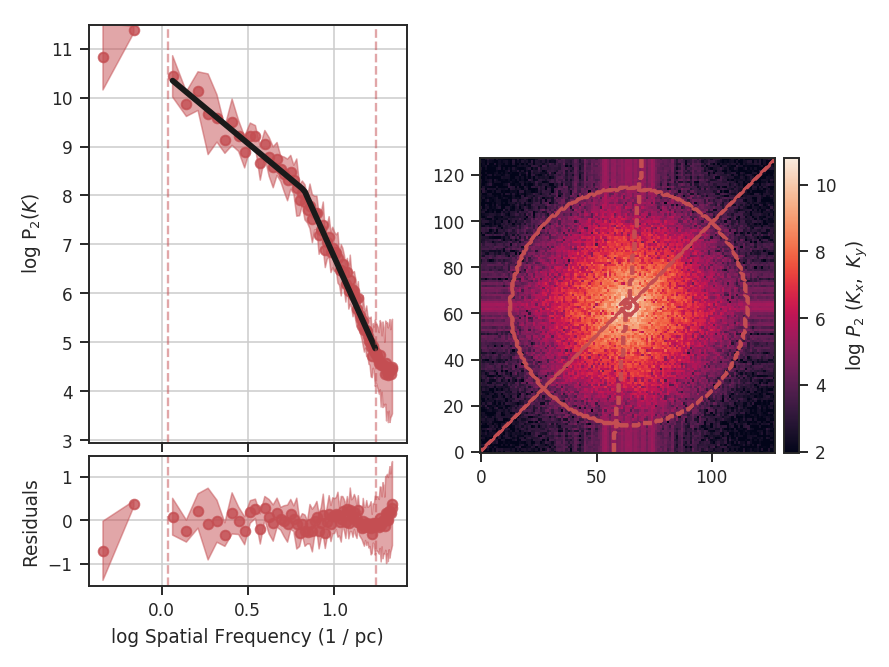

>>> pspec_masked_pad = PowerSpectrum(fits.PrimaryHDU(padded_masked_img))

>>> pspec_masked_pad.run(verbose=True, high_cut=10**-1.25 / u.pix)

OLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: y R-squared: 0.985

Model: OLS Adj. R-squared: 0.985

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 1166.

Date: Fri, 15 Feb 2019 Prob (F-statistic): 1.41e-29

Time: 13:43:42 Log-Likelihood: 35.094

No. Observations: 39 AIC: -66.19

Df Residuals: 37 BIC: -62.86

Df Model: 1

Covariance Type: HC3

==============================================================================

coef std err z P>|z| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const 3.4746 0.123 28.245 0.000 3.233 3.716

x1 -2.6847 0.079 -34.144 0.000 -2.839 -2.531

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 1.962 Durbin-Watson: 2.222

Prob(Omnibus): 0.375 Jarque-Bera (JB): 1.840

Skew: -0.489 Prob(JB): 0.399

Kurtosis: 2.580 Cond. No. 12.2

==============================================================================

The power-spectrum is similarly flattened as in the non-padded case. However, the sharp cut-off at the edges of the non-masked region lead to the Gibbs phenomenon (i.e., ringing) evident from the horizontal and vertical stripes in the 2D power-spectrum on the right. The ringing can be minimized by utilizing an apodizing kernel.

>>> delvar_masked_padded = DeltaVariance(fits.PrimaryHDU(padded_masked_img))

>>> delvar_masked_padded.run(verbose=True, xlow=2 * u.pix, xhigh=70 * u.pix) # doctest: +SKIP

WLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: y R-squared: 0.999

Model: WLS Adj. R-squared: 0.999

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 1.120e+04

Date: Fri, 15 Feb 2019 Prob (F-statistic): 3.37e-24

Time: 13:48:37 Log-Likelihood: 48.777

No. Observations: 18 AIC: -93.55

Df Residuals: 16 BIC: -91.77

Df Model: 1

Covariance Type: HC3

==============================================================================

coef std err z P>|z| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const -1.8663 0.004 -425.902 0.000 -1.875 -1.858

x1 0.9501 0.009 105.823 0.000 0.933 0.968

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 26.283 Durbin-Watson: 1.593

Prob(Omnibus): 0.000 Jarque-Bera (JB): 41.814

Skew: -2.253 Prob(JB): 8.32e-10

Kurtosis: 8.953 Cond. No. 11.6

==============================================================================

The delta-variance is similarly unaffected by the padded region. Because of the weighting functions, the convolution steps in the delta-variance do not suffer from ringing like the power-spectrum does. We note that this delta-variance curve extends to larger scales because of the padding. What is notable on these larger scales is the lack of emission, which causes the delta-variance to decrease. This is the expected behaviour when large regions of an image are masked and the user can either (i) limit the lags to smaller values, or (ii) exclude large scales from the fit (as we do in this example).

Now, we will compare the masking examples above to when noise is added to the image (without padding). We will add noise to the image drawn from a normal distribution with standard deviation of 1.:

>>> noise_rms = 1.

>>> noisy_img = img + np.random.normal(0., noise_rms, img.shape)

>>> plt.imshow(noisy_img, origin='lower')

>>> plt.colorbar()

Since the noise distribution is spatially-uncorrelated, the power-spectrum of only the noise will be 0. We expect then that the power-spectrum will be flattened on small scales due to the noise:

>>> pspec_noisy = PowerSpectrum(fits.PrimaryHDU(noisy_img))

>>> pspec_noisy.run(verbose=True, high_cut=10**-1.2 / u.pix)

OLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: y R-squared: 0.999

Model: OLS Adj. R-squared: 0.999

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 7447.

Date: Fri, 15 Feb 2019 Prob (F-statistic): 4.08e-26

Time: 13:58:28 Log-Likelihood: 47.231

No. Observations: 21 AIC: -90.46

Df Residuals: 19 BIC: -88.37

Df Model: 1

Covariance Type: HC3

==============================================================================

coef std err z P>|z| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const 2.4964 0.048 51.948 0.000 2.402 2.591

x1 -2.9054 0.034 -86.298 0.000 -2.971 -2.839

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 3.284 Durbin-Watson: 2.477

Prob(Omnibus): 0.194 Jarque-Bera (JB): 1.493

Skew: 0.450 Prob(JB): 0.474

Kurtosis: 3.948 Cond. No. 13.3

==============================================================================

The power-spectrum does indeed approach an index of 0 on small scales due to the noise. By excluding scales smaller than \(10^{1.25}\sim18\) pixels, however, we recover a index of \(-2.9\), much closer to the actual index of \(-3\) than the masking example above. The extent that the power-spectrum index will be biased by the noise will depend on the level of noise relative to the signal. An alternative approach to model the power-spectrum would be to include a noise component (e.g., Miville-Deschenes et al. 2010) but this is not currently implemented in TurbuStat.

Running delta-variance on the noisy image gives:

>>> delvar_noisy = DeltaVariance(fits.PrimaryHDU(noisy_img))

>>> delvar_noisy.run(verbose=True, xlow=10 * u.pix, xhigh=70 * u.pix)

WLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: y R-squared: 0.999

Model: WLS Adj. R-squared: 0.998

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 842.9

Date: Fri, 15 Feb 2019 Prob (F-statistic): 9.52e-12

Time: 14:17:20 Log-Likelihood: 41.456

No. Observations: 13 AIC: -78.91

Df Residuals: 11 BIC: -77.78

Df Model: 1

Covariance Type: HC3

==============================================================================

coef std err z P>|z| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const -1.8245 0.041 -45.005 0.000 -1.904 -1.745

x1 0.9480 0.033 29.034 0.000 0.884 1.012

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 7.660 Durbin-Watson: 1.670

Prob(Omnibus): 0.022 Jarque-Bera (JB): 3.768

Skew: -1.137 Prob(JB): 0.152

Kurtosis: 4.336 Cond. No. 20.7

==============================================================================

The delta-variance slope is flatter by about the same amount as in the masked image example above (\(0.95\)). Thus masking and noise (at this level) have the same effect on the slope of the delta-variance.

From these examples, we see that the power-spectrum is more biased by masking than by keeping noisy regions in the image. The delta-variance is similarly biased in both cases because of how noisy regions are down-weighted in the convolution step.

Note

We encourage users to test a statistic with and without masking their data to determine how the statistic is affected by masking.

Where noise matters¶

Noise will affect all the statistics and metrics in TurbuStat to some extent. This section lists common issues that may be encountered with observational data.

- The previous section shows an example of how noise flattens a power-spectrum. This will effect the spatial power-spectrum, MVC, VCA, VCS (at small scales), the Wavelet transform, and the delta-variance. If the noise level is moderate, the range that is fit can be altered to avoid the scales where noise severely flattens the power-spectrum or equivalent relation.

- Fits to the PDF can be affected by noise. These values will tend to cluster the low values in an image to around 0. If the noise is (mostly) uncorrelated, the noise component will be a Gaussian. A minimum value to include in the PDF should be set to avoid this region. Furthermore, the default log-normal model cannot handle negative values and will raise an error in this case.

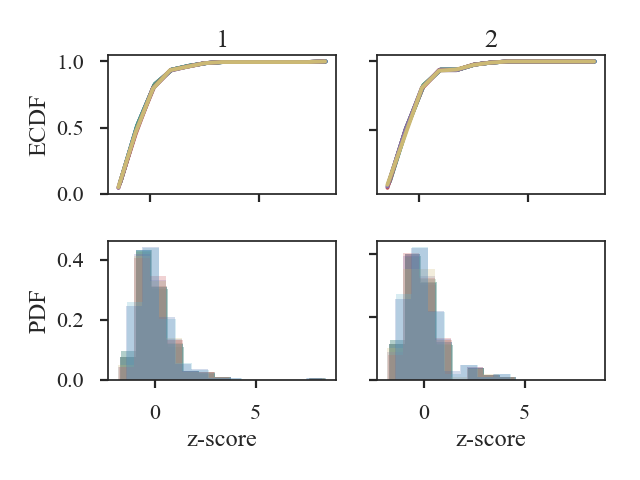

- Many of the distance metrics are defined in terms of the significance of the difference between two values. For example, the power-spectrum distance is the absolute difference between two indices normalized by the square root of the sum of the variance from the fit uncertainty (\(d=|\beta_1 - \beta_2|\, /\, \sqrt{\sigma_1^2 + \sigma_2^2}\)). If one data set is significantly noisier than the other, this will _lower_ the distance. It is important to compare all distance to a common baseline. This will determine the significance of a distance rather than its value. Koch et al. 2017 explore this in detail.

Statistics¶

Using statistics classes¶

The statistics implemented in TurbuStat are python classes. This structure allows for derived properties to persist without having to manually carry them forward through each step.

Using most of the statistic classes will involved two steps:

Initialization – The data, relevant WCS information, and other unchanging properties (like the distance) are specified here. Some of the statistics calculated at specific scales (like

WaveletorSCF) can have those scales set here, too. Below is an example usingWavelet:>>> from turbustat.statistics import Wavelet >>> import numpy as np >>> from astropy.io import fits >>> from astropy.units import u >>> hdu = fits.open("file.fits")[0] # doctest: +SKIP >>> spatial_scales = np.linspace(0.1, 1.0, 20) * u.pc # doctest: +SKIP >>> wave = Wavelet(hdu, scales=spatial_scales, ... distance=260 * u.pc) # doctest: +SKIP

The run function – For most use-cases, the

runfunction can be used to compute the statistic. All of the statistics have this function. It will compute the statistic, perform any relevant fitting, and optionally create a summary plot. The docstring for each of therunfunctions describe the parameters that can be changed from this function. The parameters that are critical to the behaviour of the statistic can all be set fromrun. Continuing with theWaveletexample from above, therunfunction is called as:>>> wave.run(verbose=True, xlow=0.2 * u.pc, xhigh=0.8 * u.pc) # doctest: +SKIP

This function will run the wavelet transform and fit the relation between the given bounds (xlow and xhigh). With verbose=True, a summary plot is returned.

What if you need to set parameters not accessible from run? run wraps multiple steps in one function, however, the statistic can be run in steps when fine-tuning is needed for a particular data set. Each of the statistics has at least one computational step. For Wavelet, there are two steps: (1) computing the transform (compute_transform) and (2) fitting the log of the transform (fit_transform). Running these two functions is equivalent to using run.

The statistics also have plotting functions. From run, these functions are called whenever verbose=True is given. All of the plotting functions start with plot_; for Wavelet, the plotting function is plot_transform. Supplying a save_name to this function will save the figure, the x-units can also be set for spatial transforms (like the wavelet transform) as pixel, angular, or physical (when a distance is given) units, and additional arguments can be given to set the colours and markers used in the plot.

Statistic classes can also be saved or loaded as pickle files. Saving is performed with the save_results function:

>>> wave.save_results("wave_file.pkl", keep_data=False) # doctest: +SKIP

Whether to include the data in saved file is set with keep_data. By default, the data is not saved to save storage space.

Note

If the statistic is not saved with the data, it cannot be recomputed after loading.

Loading the statistic from a saved file uses the load_results function:

>>> new_wave = Wavelet.load_results("wav_file.pkl") # doctest: +SKIP

Unless the data is saved, everything but the data is new accessible from new_wave.

Bispectrum¶

Overview¶

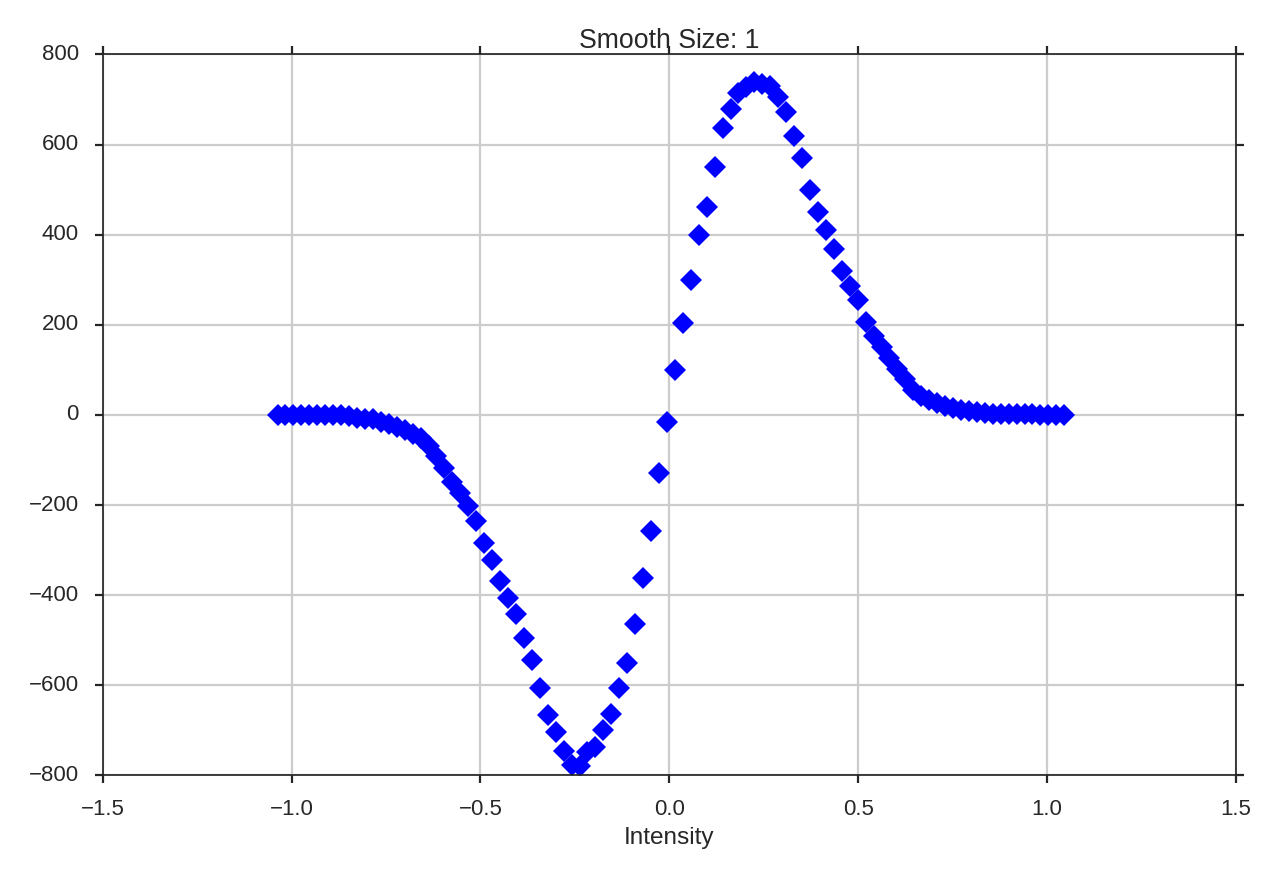

The bispectrum is the Fourier transform of the three-point covariance function. It represents the next higher-order expansion upon the more commonly-used two-point statistics, where the autocorrelation function is the Fourier transform of the power spectrum. The bispectrum is computed using:

where \(\ast\) denotes the complex conjugate, \(F\) is the Fourier transform of some signal, and \(k_1,\,k_2\) are wavenumbers.

The bispectrum retains phase information that is lost in the power spectrum and is therefore useful for investigating phase coherence and coupling.

The use of the bispectrum in the ISM was introduced by Burkhart et al. 2009 and is further used in Burkhart et al. 2010 and Burkhart et al. 2016.

The phase information retained by the bispectrum requires it to be a complex quantity. A real, normalized version can be expressed through the bicoherence. The bicoherence is a measure of phase coupling alone, where the maximal values of 1 and 0 represent complete coupled and uncoupled, respectively. The form that is used here is defined by Hagihira et al. 2001:

The denominator normalizes by the “power” at the modes \(k_1,\,k_2\); this is effectively dividing out the value of the power spectrum, leaving a fractional difference that is entirely the result of the phase coupling. Alternatively, the denominator can be thought of as the value attained if the modes \(k_1\,k_2\) are completely phase coupled, and therefore is the maximal value attainable.

Using¶

The data in this tutorial are available here.

We need to import the Bispectrum code, along with a few other common packages:

>>> from turbustat.statistics import Bispectrum

>>> from astropy.io import fits

>>> import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

Next, we load in the data:

>>> moment0 = fits.open("Design4_flatrho_0021_00_radmc_moment0.fits")[0] # doctest: +SKIP

While the bispectrum can be extended to sample in N-dimensions, the current implementation requires a 2D input. In all previous work, the computation was performed on an integrated intensity or column density map.

First, the Bispectrum class is initialized:

>>> bispec = Bispectrum(moment0) # doctest: +SKIP

The bispectrum requires only the image, not a header, so passing any arbitrary 2D array will work.

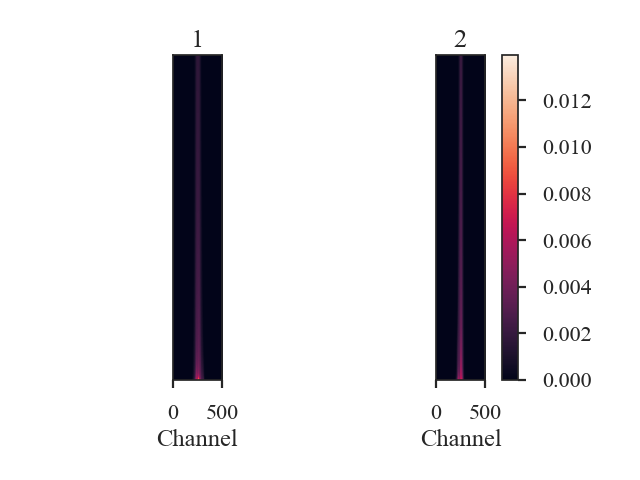

Even using a small 2D image (128x128 here), the number of possible combinations for \(k_1,\,k_2\) is massive (the maximum value of \(k_1,\,k_2\) is half of the largest dimension size in the image). To save time, we can randomly sample some number of phases for each value of \(k_1,\,k_2\) (so \(k_1 + k_2\), the coupling term, changes). This is set by nsamples. There is shot noise associated with this random sampling, and the effect of changing nsamples should be tested. For this example, structure begins to become apparent with about 1000 samples. The figures here use 10000 samples to make the structure more evident. This will take about 10 minutes to run on this image!

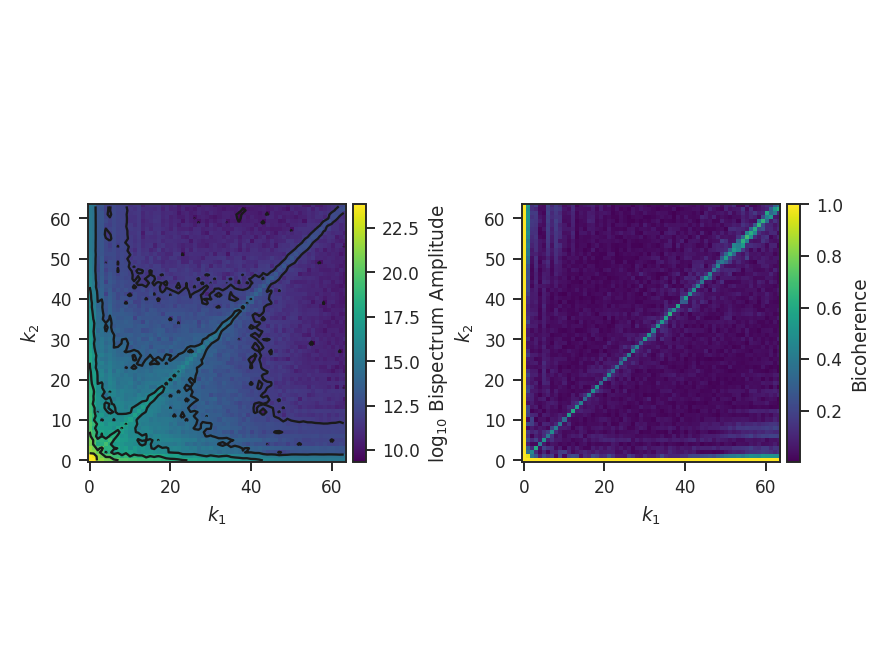

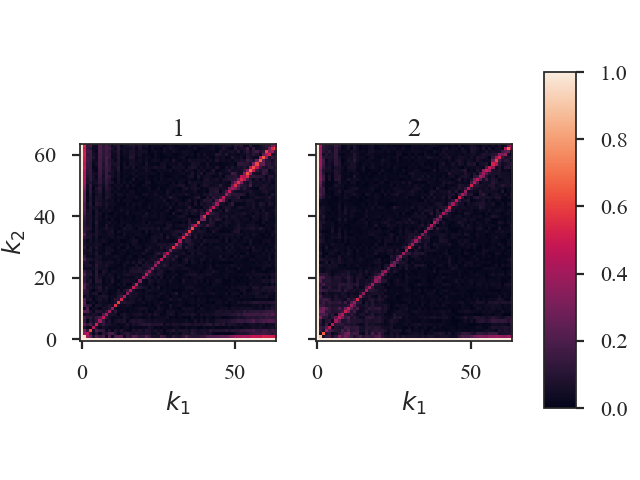

The bispectrum and bicoherence maps are computed with run:

>>> bispec.run(verbose=True, nsamples=10000) # doctest: +SKIP

run only performs a single step: compute_bispectrum. For this, there are two optional inputs that may be set:

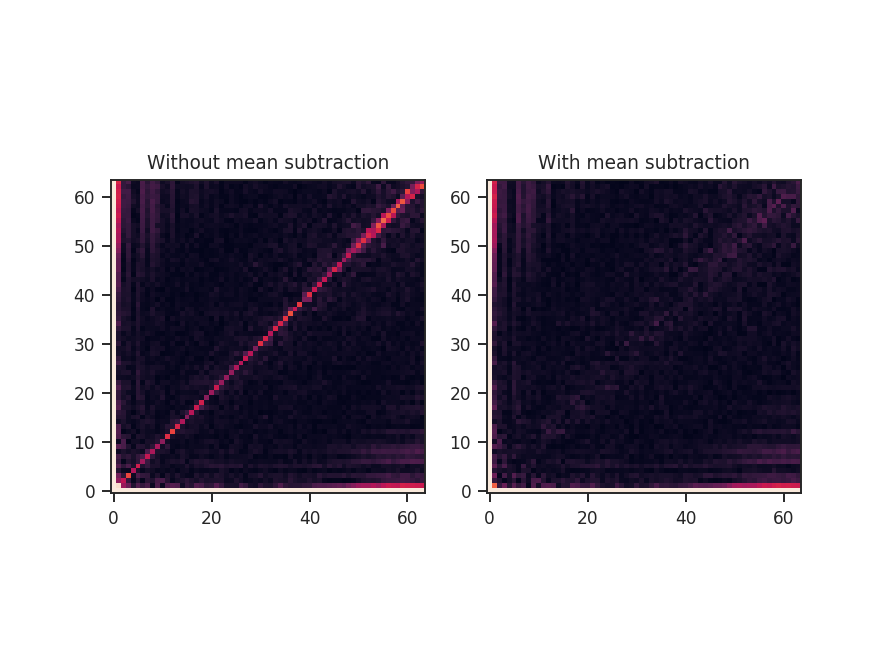

>>> bispec.run(nsamples=10000, mean_subtract=True, seed=4242424) # doctest: +SKIP

seed sets the random seed for the sampling, and mean_subtract removes the mean from the data before computing the bispectrum. This removes the “zero frequency” power defined based on the largest scale in the image that gives the phase coupling along \(k_1 = k_2\) line. Removing the mean highlights the non-linear mode interactions.

The figure shows the effect on the bicoherence from subtracting the mean. The colorbar is limited between 0 and 1, with black representing 1.

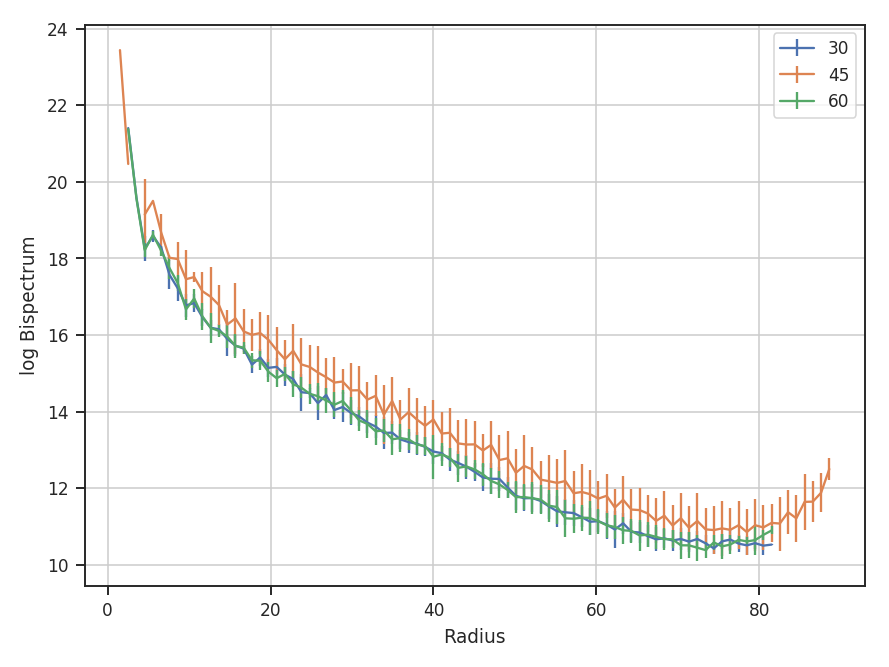

Both radial and azimuthal slices can be extracted from the bispectrum to examine how its properties vary with angle and radius. Using the non-mean subtracted example, radial slices can be returned with:

>>> rad_slices = bispec.radial_slices([30, 45, 60] * u.deg, 20 * u.deg, value='bispectrum_logamp') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.errorbar(rad_slices[30][0], rad_slices[30][1], yerror=rad_slices[30][2], label='30') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.errorbar(rad_slices[45][0], rad_slices[45][1], yerror=rad_slices[45][2], label='45') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.errorbar(rad_slices[60][0], rad_slices[60][1], yerror=rad_slices[60][2], label='60') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.legend() # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.xlabel("Radius") # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.ylabel("log Bispectrum") # doctest: +SKIP

Three slices are returned, centered at 30, 45, and 60 degrees. The width of each slice is 20 degrees. rad_slices is a dictionary whose keys are the (rounded to the nearest integer) center angles given. Each entry in the dictionary has the bin centers ([0]), values ([1]), and standard deviations ([2]). The center angles and slice width can be given in any angular unit. By default, the averaging is over the bispectrum amplitudes. By passing value='bispectrum_logamp', the log of the amplitudes are instead averaged over. The bicoherence array can also be averaged over with value='bicoherence'. The size of the bins can also be changed by passing bin_width to radial_slices; the default is 1.

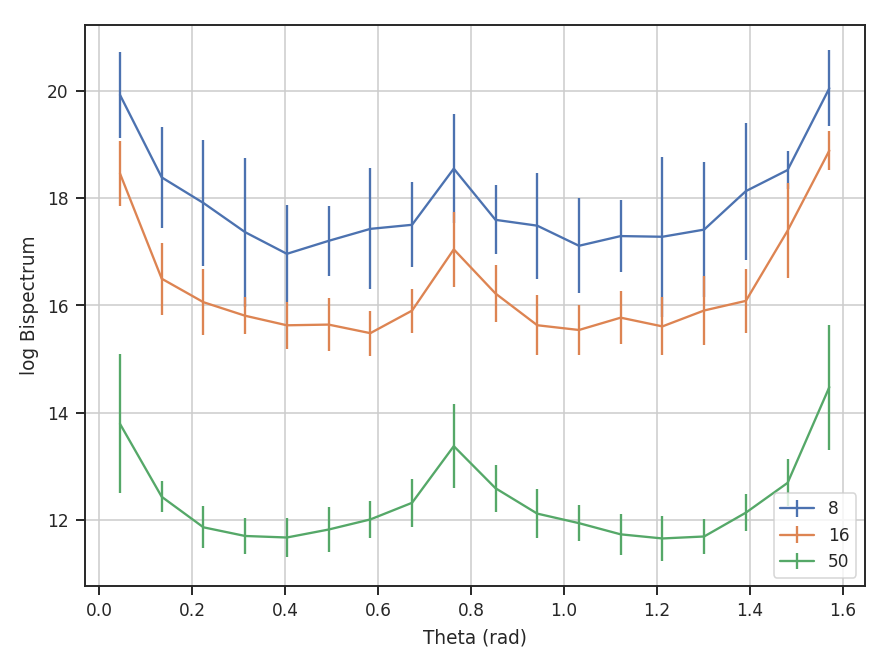

The azimuthal slices are similarly calculated:

>>> azim_slices = tester.azimuthal_slice([8, 16, 50], 10, value='bispectrum_logamp', bin_width=5 * u.deg) # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.errorbar(azim_slices[8][0], azim_slices[8][1], yerror=azim_slices[8][2], label='8') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.errorbar(azim_slices[16][0], azim_slices[16][1], yerror=azim_slices[16][2], label='16') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.errorbar(azim_slices[50][0], azim_slices[50][1], yerror=azim_slices[50][2], label='50') # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.legend() # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.xlabel("Theta (rad)") # doctest: +SKIP

>>> plt.ylabel("log Bispectrum") # doctest: +SKIP

The slices are returned over angles 0 to \(\pi / 2\). With the azimuthal slices, the center radii, in units of the wavevectors, are given and a radial width (10) is specified for all. If different widths are needed, multiple values for the width can be given, though the length must match the length of the center radii.

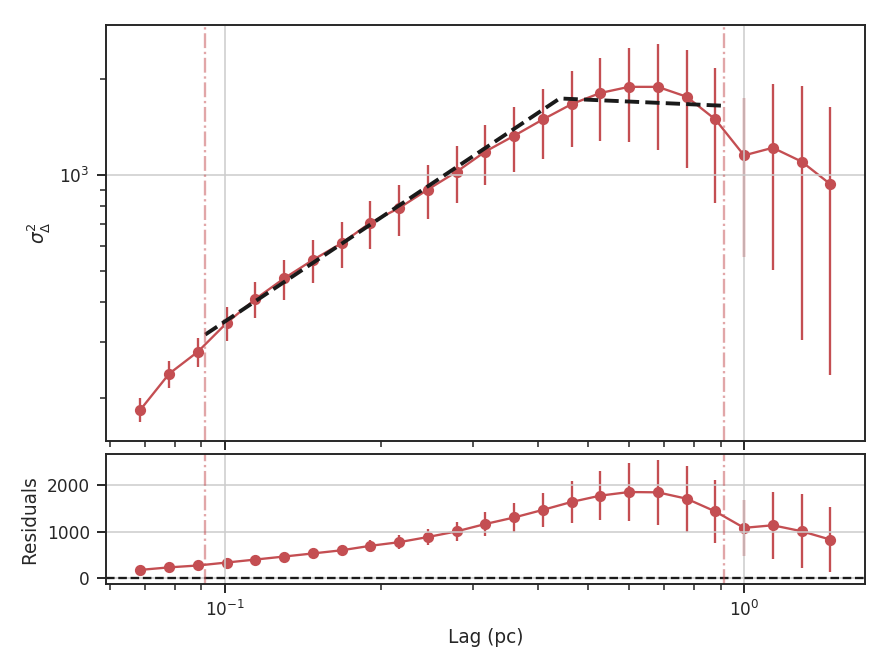

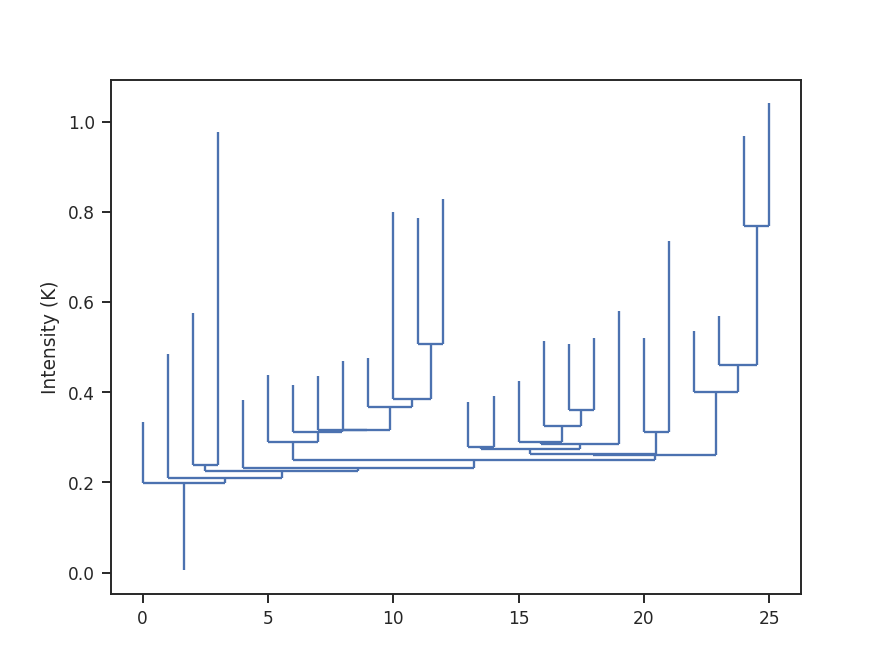

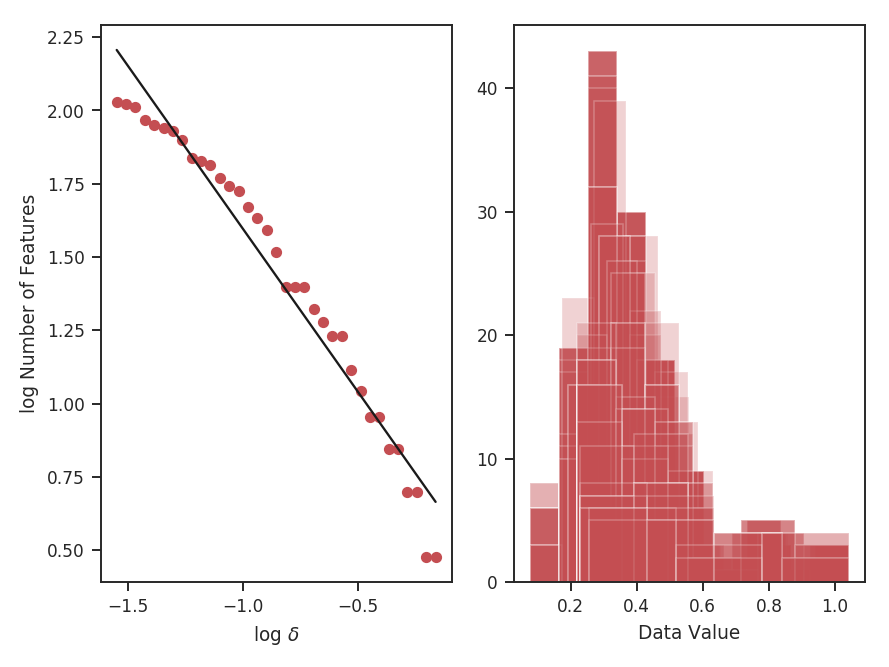

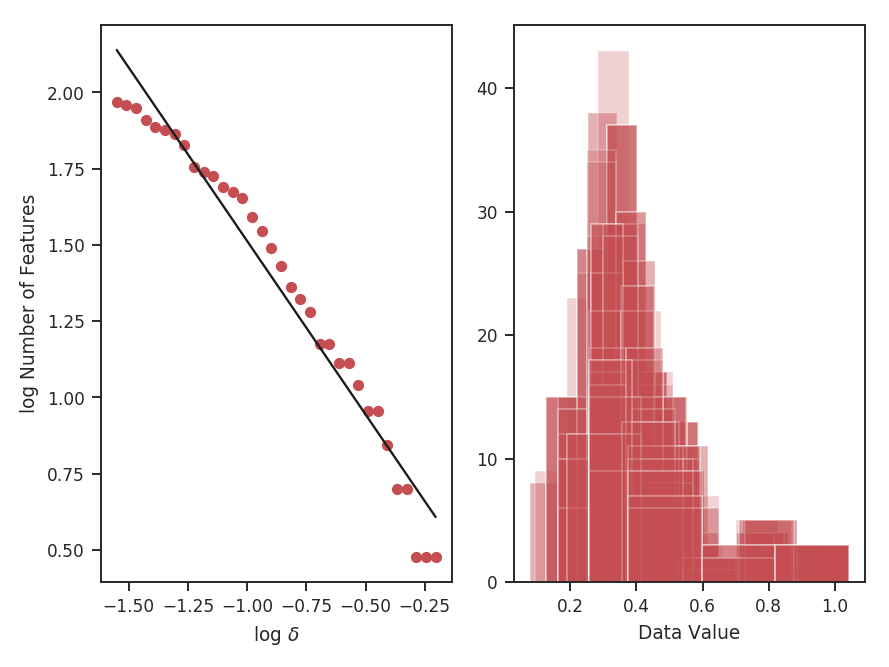

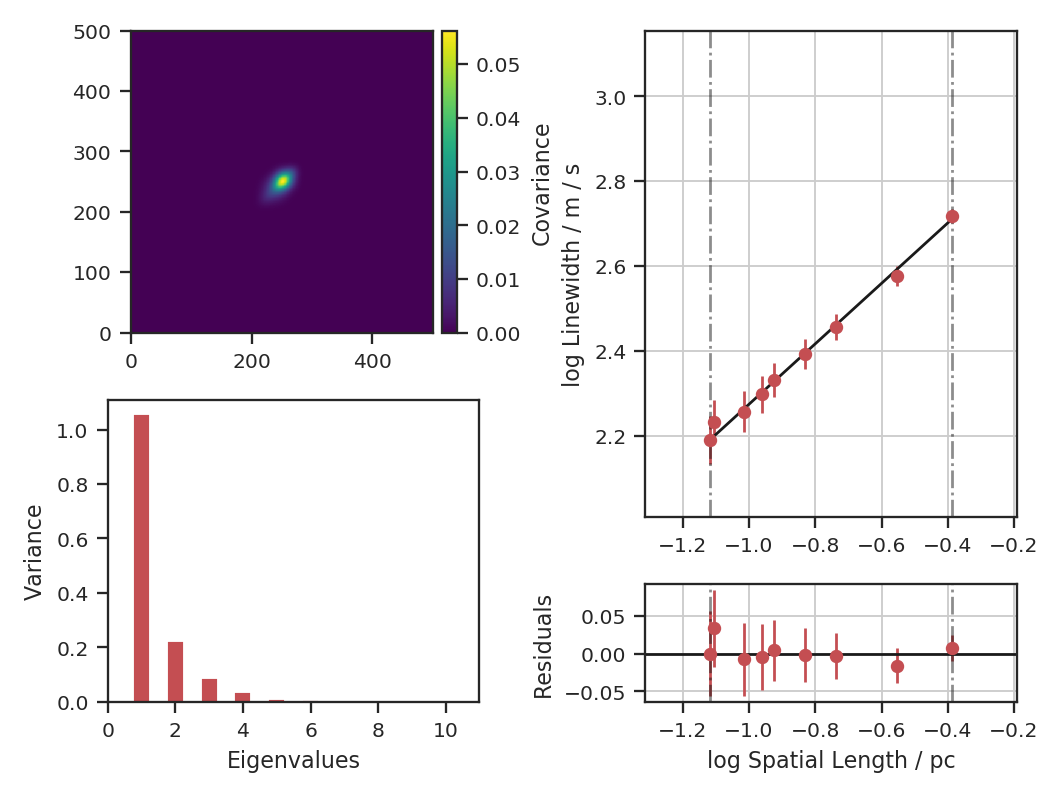

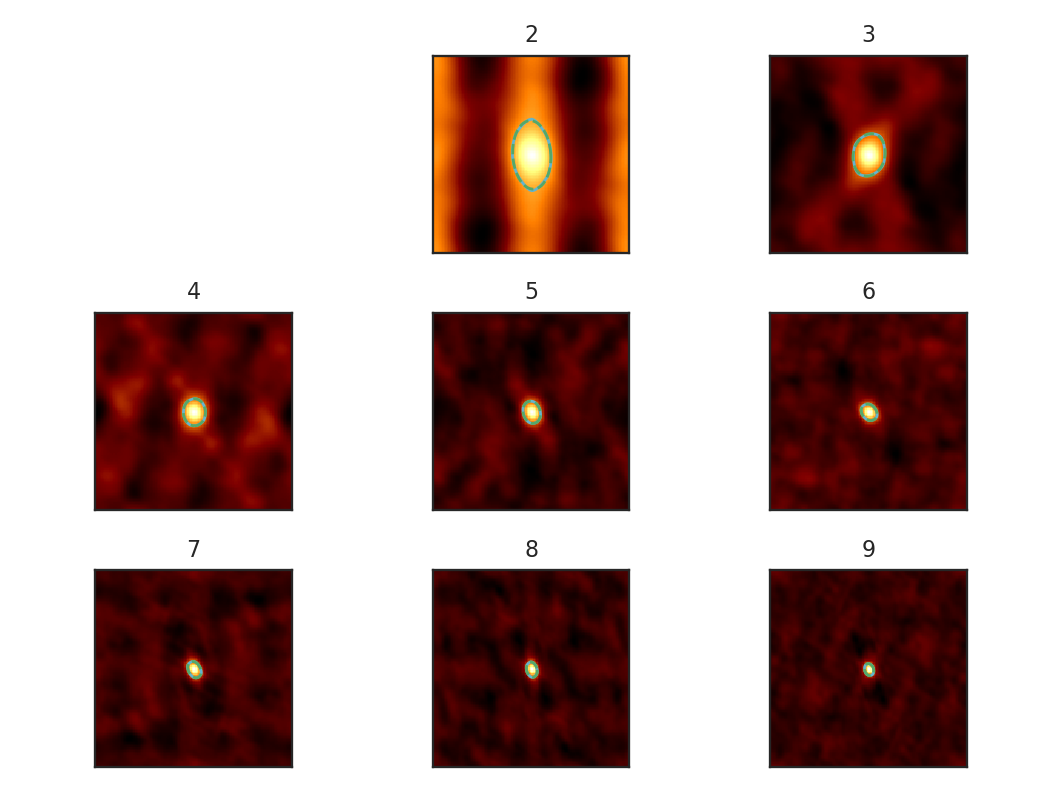

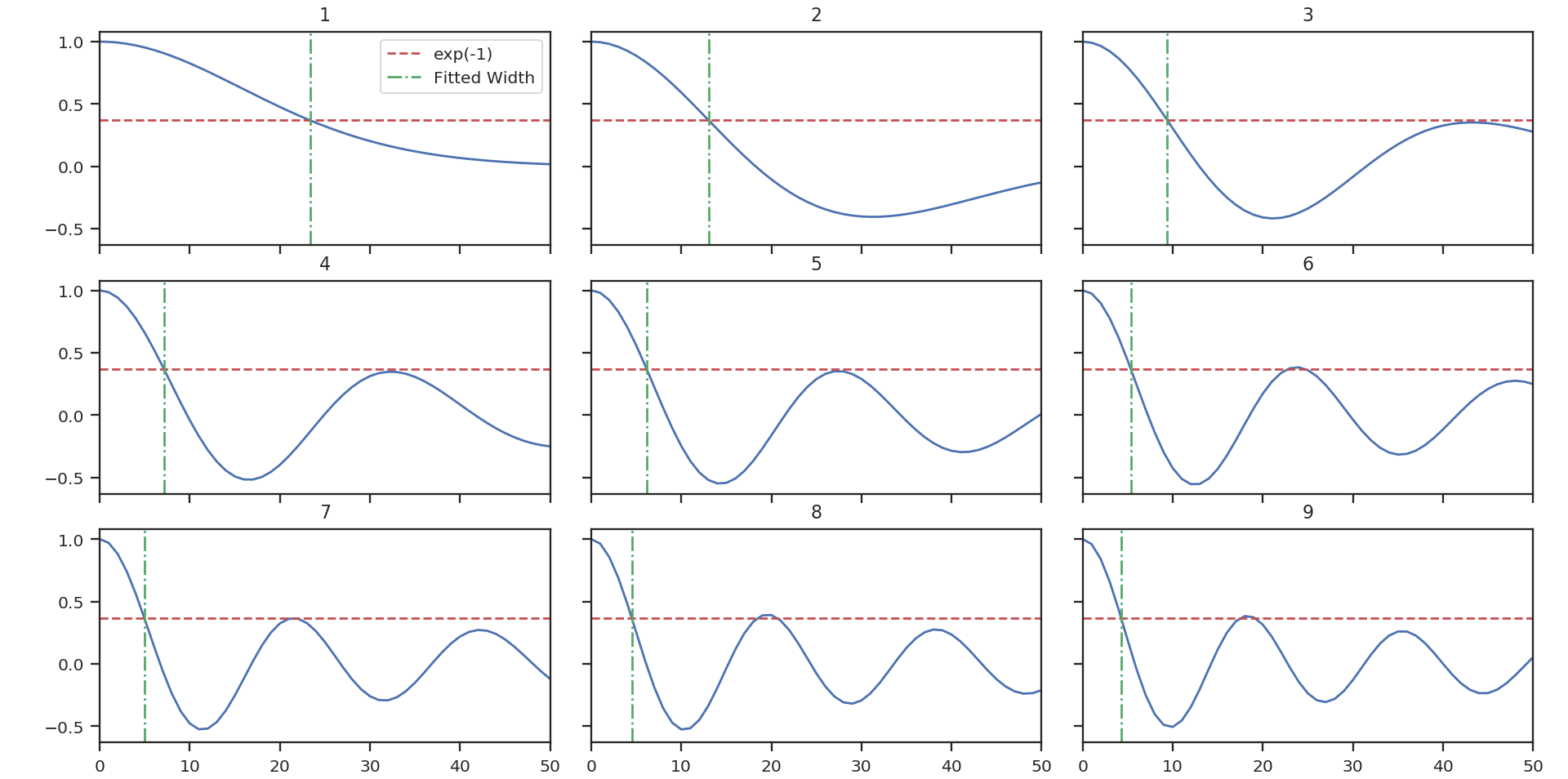

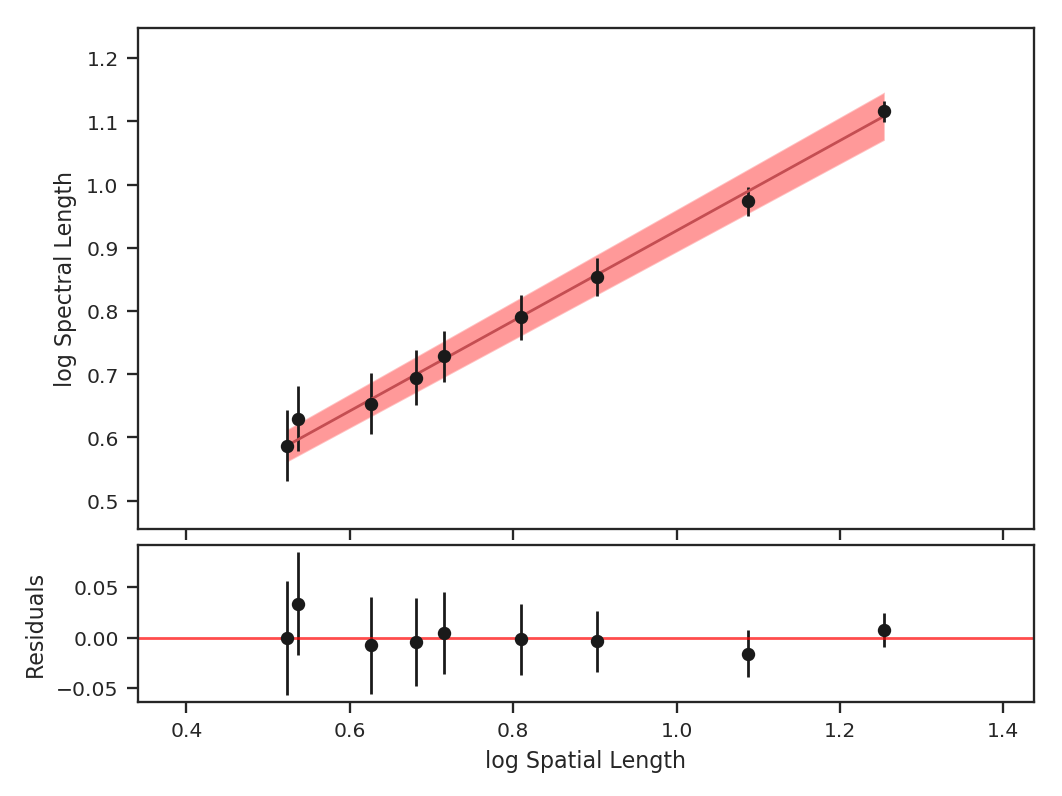

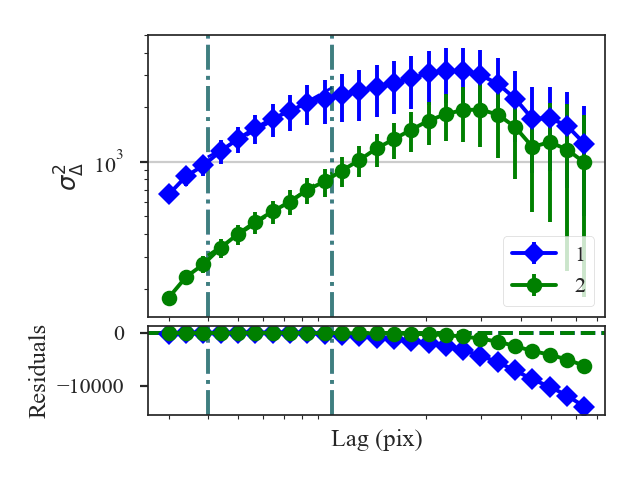

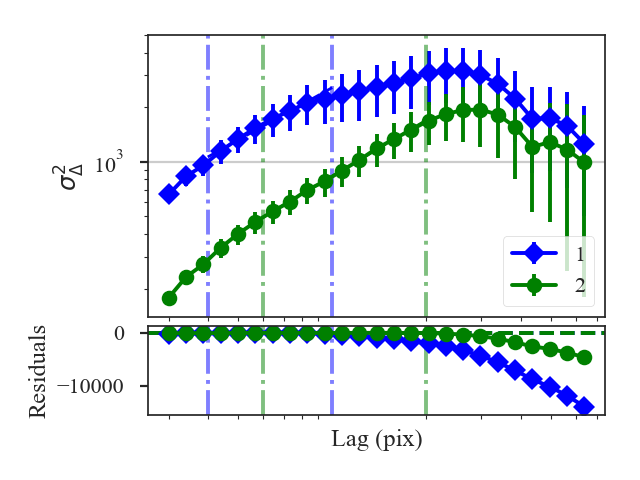

Delta-Variance¶

Overview¶

The \(\Delta\)-variance technique was introduced by Stutzki et al. 1998 as a generalization of Allan-variance, a technique used to study the drift in instrumentation. They found that molecular cloud structures are well characterized by fractional Brownian motion structure, which results from a power-law power spectrum with a random phase distribution. The technique was extended by Bensch et al. 2001. to account for the effects of beam smoothing and edge effects on a discretely sampled grid. With this approach, they identified a functional form to recover the index of the near power-law relation. The technique was extended again by Ossenkopf at al. 2008a, where the computation using filters of different scales was moved into the Fourier domain, allowing for a significant improvement in speed. The following description uses the Fourier-domain formulation.

Delta-variance measures the amount of structure on a given range of scales. Each delta-variance point is calculated by filtering an image with an azimuthally symmetric kernel - a French hat or Mexican hat (Ricker) kernels - and computing the variance of the filtered map. Due to the effects of a finite grid that typically does not have periodic boundaries and the effects of noise, Ossenkopf at al. 2008a proposed a convolution based method that splits the kernel into its central peak and outer annulus, convolves the separate regions, and subtracts the annulus-convolved map from the peak-convolved map. The Mexican-hat kernel separation can be defined using two Gaussian functions. A weight map was also introduced to minimize noise effects where there is low S/N regions in the data. Altogether, this is expressed as:

where \(r\) is the kernel size, \(G\) is the convolved image map, and \(W\) is the convolved weight map. The delta-variance is then,

where \(W_{\rm tot}(r) = W_{\rm core}(r)\,W_{\rm ann}(r)\).

Since the kernel is separated into two components, the ratio between their widths can be set independently. Ossenkopf at al. 2008a find an optimal ratio of 1.5 for the Mexican-hat kernel, which is the element used in TurbuStat.

Performing this operation yields a power-law-like relation between the scales \(r\) and the delta-variance. This power-law relation measured in the real-domain is analogous to the two-point structure function (e.g., Miesch & Bally 1994). Its use of the convolution kernel, as well as handling for map edges, makes it faster to compute and more robust to oddly-shaped regions of signal.

This technique shares many similarities to the Wavelet transform.

Using¶

The data in this tutorial are available here.

We need to import the DeltaVariance code, along with a few other common packages:

>>> from turbustat.statistics import DeltaVariance

>>> from astropy.io import fits

Then, we load in the data and the associated error array:

>>> moment0 = fits.open("Design4_flatrho_0021_00_radmc_moment0.fits")[0] # doctest: +SKIP

>>> moment0_err = fits.open("Design4_flatrho_0021_00_radmc_moment0.fits")[1] # doctest: +SKIP

Next, we initialize the DeltaVariance class:

>>> delvar = DeltaVariance(moment0, weights=moment0_err, distance=250 * u.pc) # doctest: +SKIP

The weight array is optional but is recommended to down-weight noisy data (particularly near the map edge). Note that this is not the exact form of the weight array used by Ossenkopf at al. 2008b; they use the square root of the number of elements along the line of sight used to create the integrated intensity map. This doesn’t take into account the varying S/N of each element used, however. In the case with the simulated data, the two are nearly identical, since the noise value associated with each element is constant. If no weights are given, a uniform array of ones is used.

To compute the delta-variance curve, the image is convolved with a set of kernels. The width of each kernel is referred to as the “lag.” By default, 25 lag values will be used, logarithmically spaced between 3 pixels to half of the minimum axis size. Alternative lags can be specified by setting the lags keyword. If a ndarray is passed, it is assumed to be in pixel units. Lags can also be given in angular units using astropy.units.Quantity objects. The diameter between the inner and outer convolution kernels is set by diam_ratio. By default, this is set to 1.5 (Ossenkopf at al. 2008a).

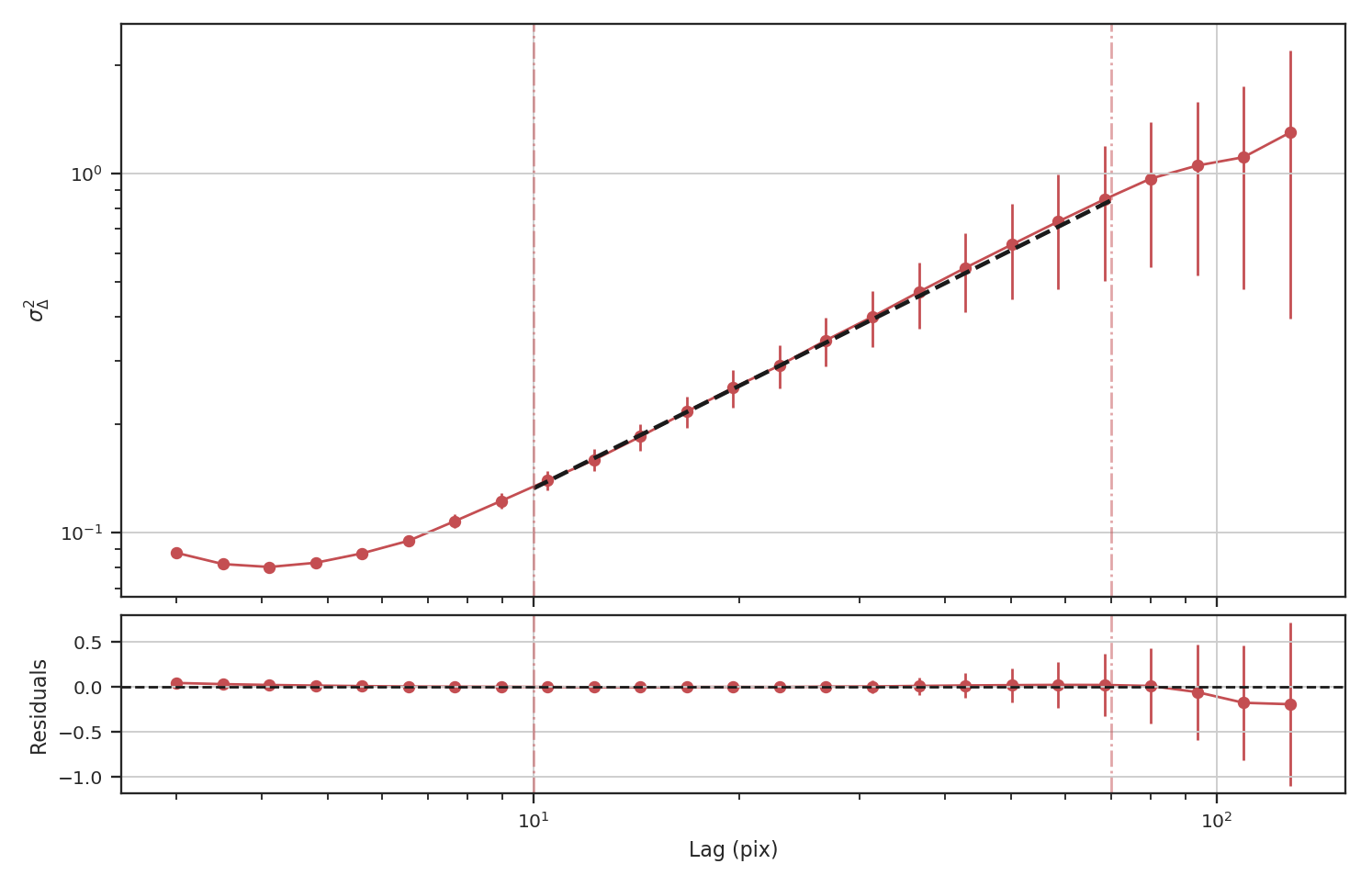

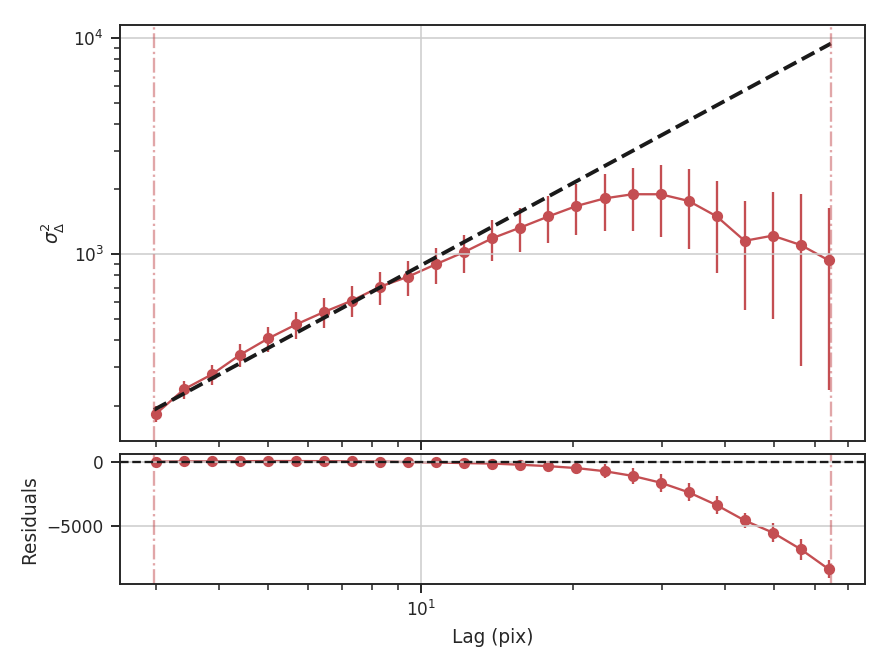

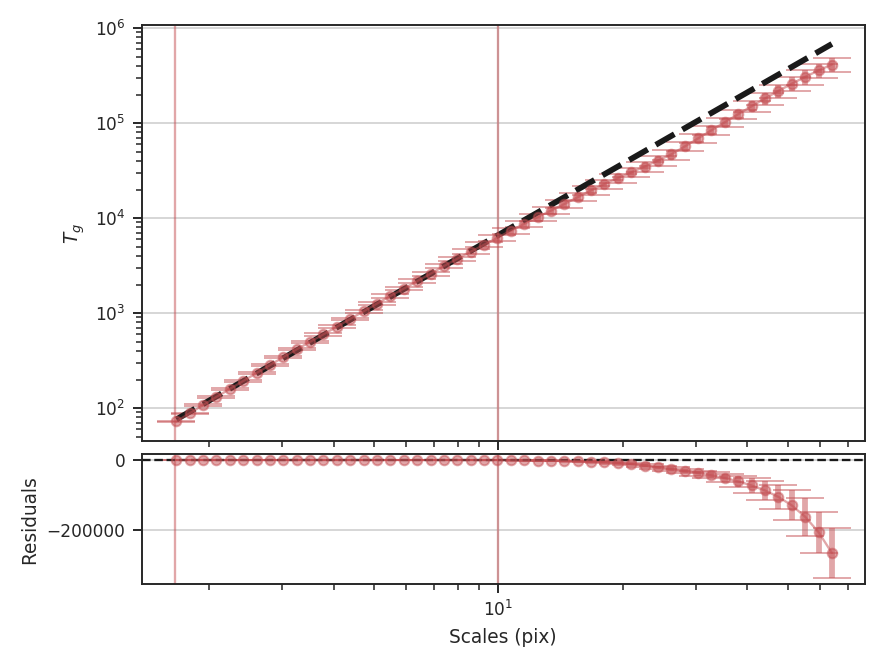

The entire process is performed through run:

>>> delvar.run(verbose=True, xunit=u.pix) # doctest: +SKIP

WLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: y R-squared: 0.946

Model: WLS Adj. R-squared: 0.943

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 400.2

Date: Wed, 18 Oct 2017 Prob (F-statistic): 4.80e-16

Time: 18:38:51 Log-Likelihood: 13.625

No. Observations: 25 AIC: -23.25

Df Residuals: 23 BIC: -20.81

Df Model: 1

Covariance Type: nonrobust

==============================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const 1.6826 0.036 46.701 0.000 1.608 1.757

x1 1.2654 0.063 20.006 0.000 1.135 1.396

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 0.195 Durbin-Watson: 0.506

Prob(Omnibus): 0.907 Jarque-Bera (JB): 0.403

Skew: -0.047 Prob(JB): 0.818

Kurtosis: 2.385 Cond. No. 10.6

==============================================================================

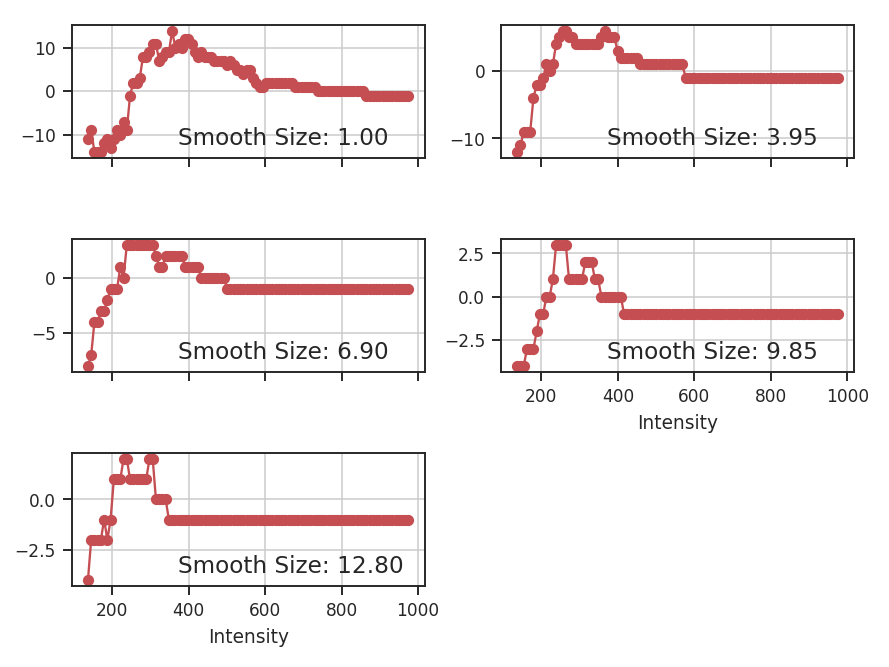

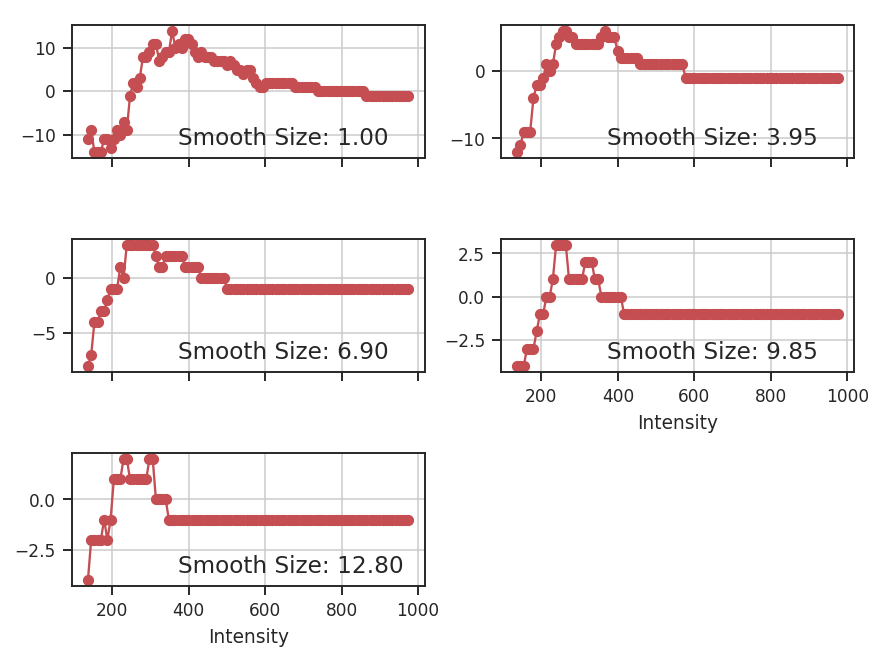

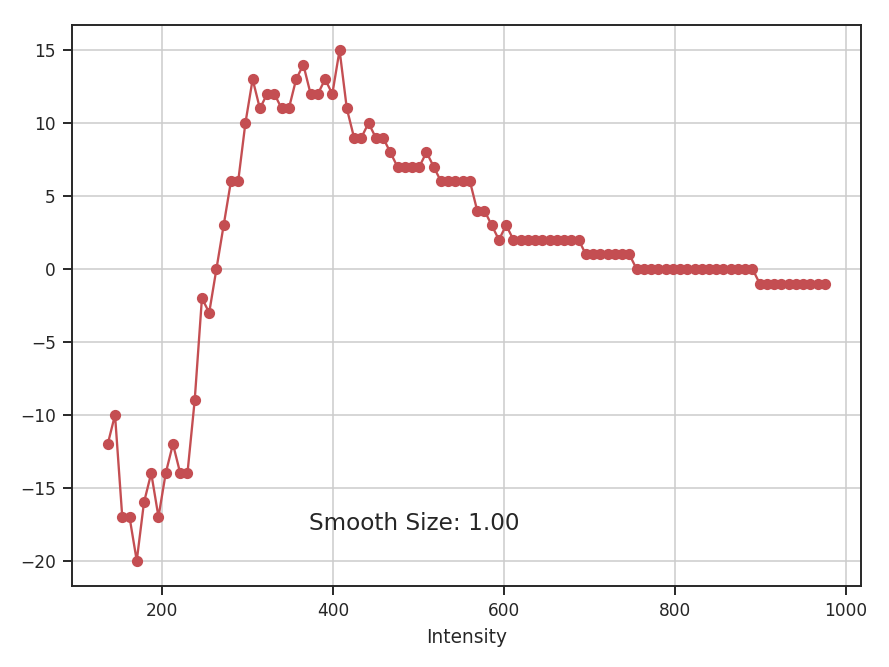

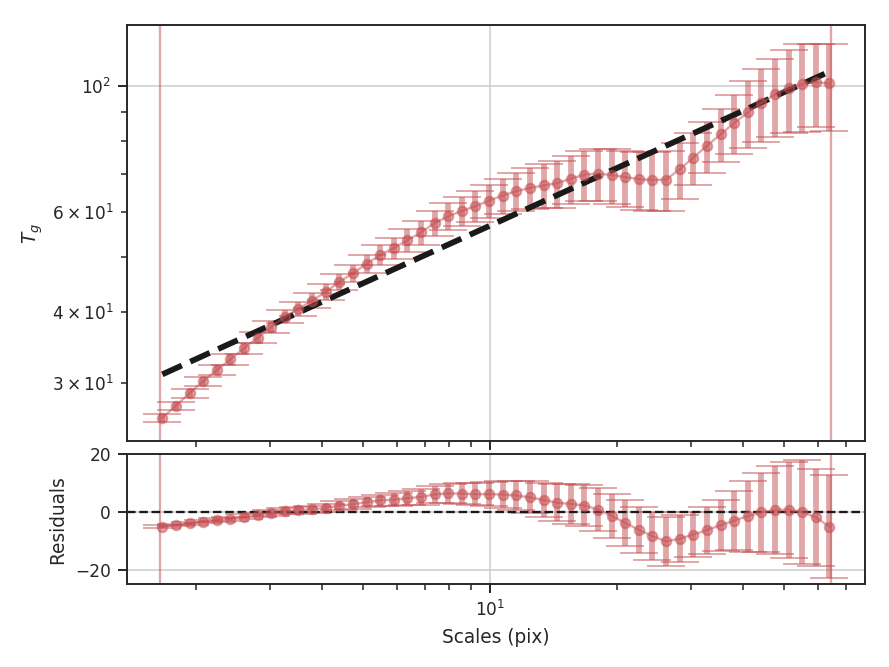

xunit is the unit the lags will be converted to in the plot. The plot includes a linear fit to the Delta-variance curve, however there is a significant deviation from a single power-law on large scales. We can restrict the fitting to reflect this:

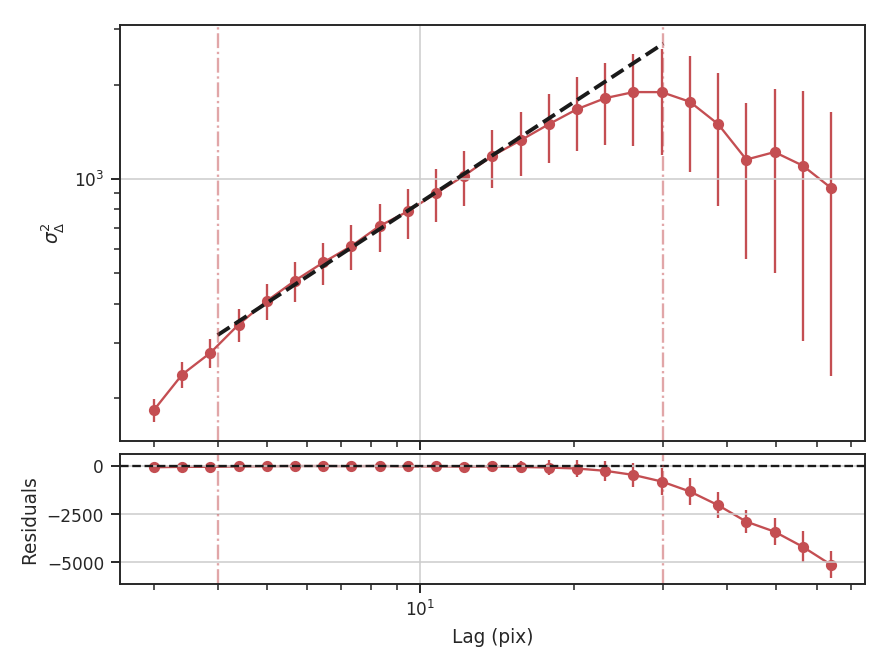

>>> delvar.run(verbose=True, xunit=u.pix, xlow=4 * u.pix, xhigh=30 * u.pix) # doctest: +SKIP

WLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: y R-squared: 0.994

Model: WLS Adj. R-squared: 0.993

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 2167.

Date: Wed, 18 Oct 2017 Prob (F-statistic): 9.44e-17

Time: 18:38:52 Log-Likelihood: 38.238

No. Observations: 16 AIC: -72.48

Df Residuals: 14 BIC: -70.93

Df Model: 1

Covariance Type: nonrobust

==============================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const 1.8620 0.017 106.799 0.000 1.825 1.899

x1 1.0630 0.023 46.549 0.000 1.014 1.112

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 0.142 Durbin-Watson: 0.746

Prob(Omnibus): 0.931 Jarque-Bera (JB): 0.271

Skew: -0.182 Prob(JB): 0.873

Kurtosis: 2.475 Cond. No. 11.4

==============================================================================

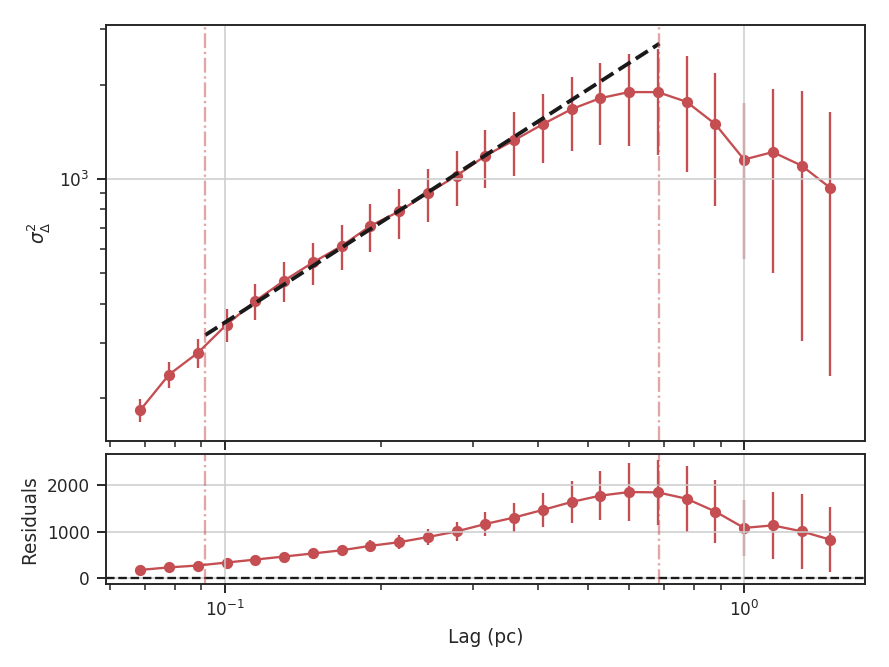

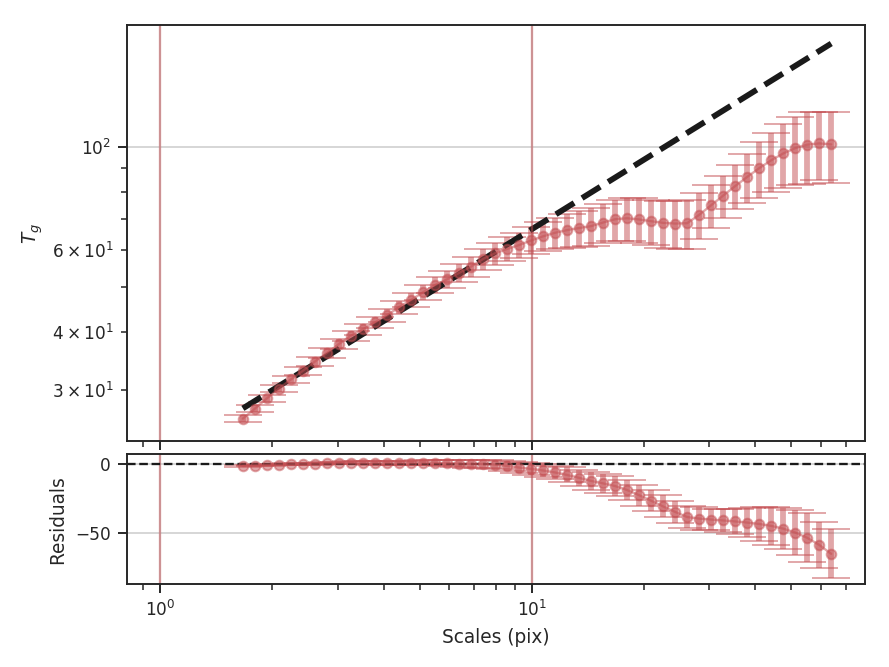

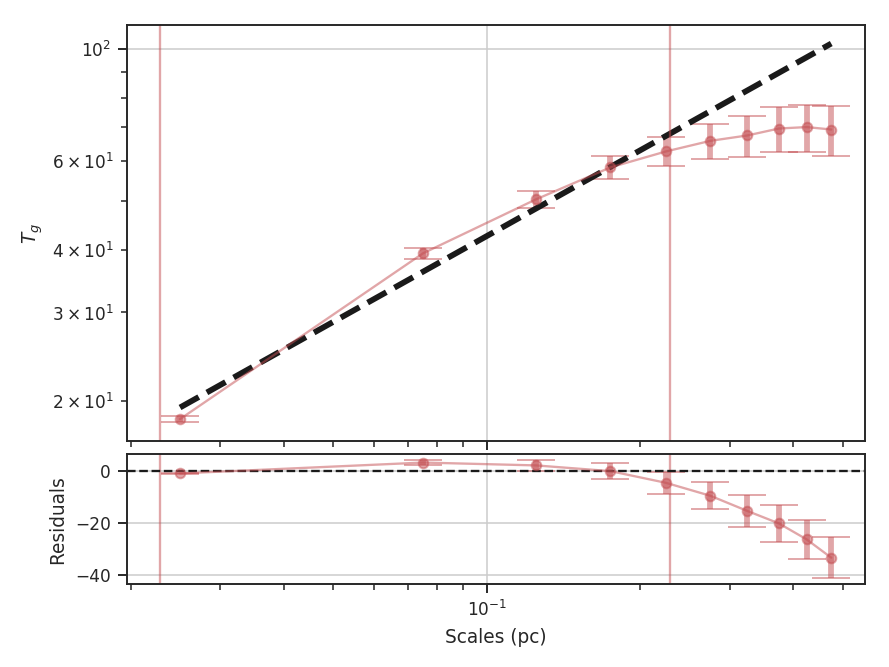

xlow, xhigh, and xunit can also be passed any angular unit, and since a distance was given, physical units can also be passed. For example, using the previous example:

>>> delvar.run(verbose=True, xunit=u.pc, xlow=4 * u.pix, xhigh=30 * u.pix) # doctest: +SKIP

WLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: y R-squared: 0.994

Model: WLS Adj. R-squared: 0.993

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 2167.

Date: Wed, 18 Oct 2017 Prob (F-statistic): 9.44e-17

Time: 18:38:52 Log-Likelihood: 38.238

No. Observations: 16 AIC: -72.48

Df Residuals: 14 BIC: -70.93

Df Model: 1

Covariance Type: nonrobust

==============================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const 1.8620 0.017 106.799 0.000 1.825 1.899

x1 1.0630 0.023 46.549 0.000 1.014 1.112

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 0.142 Durbin-Watson: 0.746

Prob(Omnibus): 0.931 Jarque-Bera (JB): 0.271

Skew: -0.182 Prob(JB): 0.873

Kurtosis: 2.475 Cond. No. 11.4

==============================================================================

Since the Delta-variance is based on a series of convolutions, there is a choice for how the boundaries should be treated. This is set by the boundary keyword in run. By default, boundary='wrap' as is appropriate for simulated data in a periodic box. If the data is not periodic in the spatial dimensions, boundary='fill' should be used. This mode pads the edges of the data based on the size of the convolution kernel used.

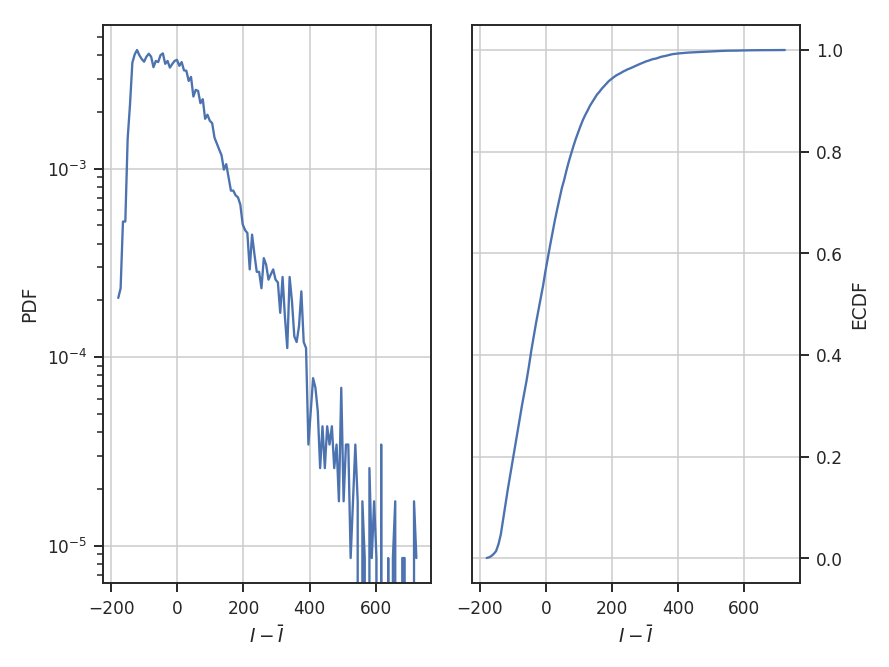

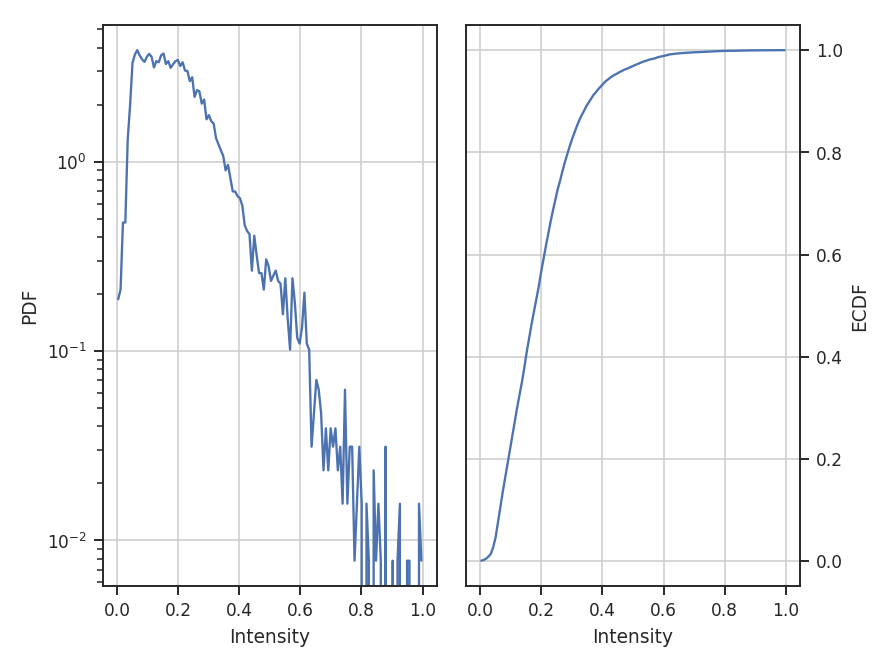

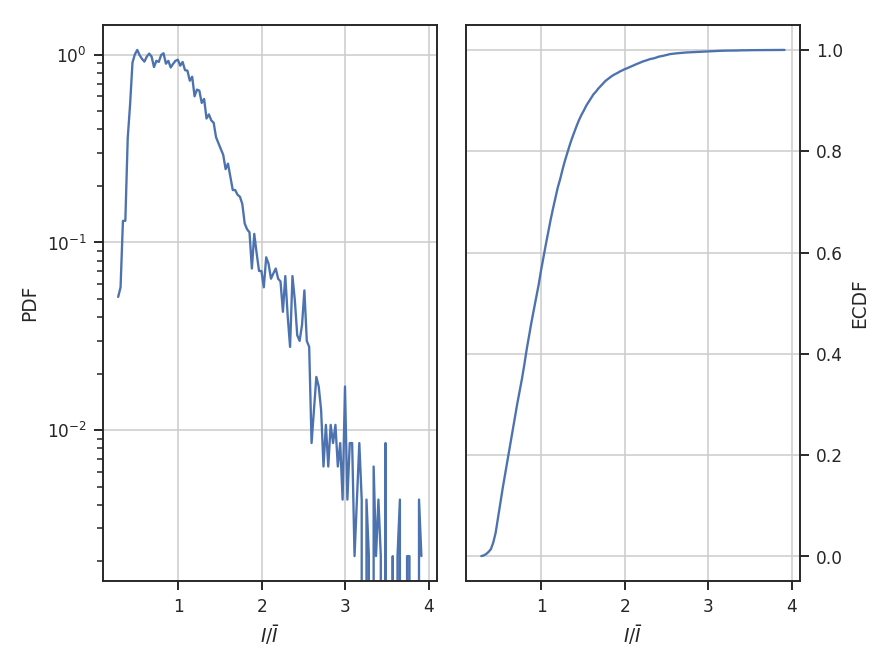

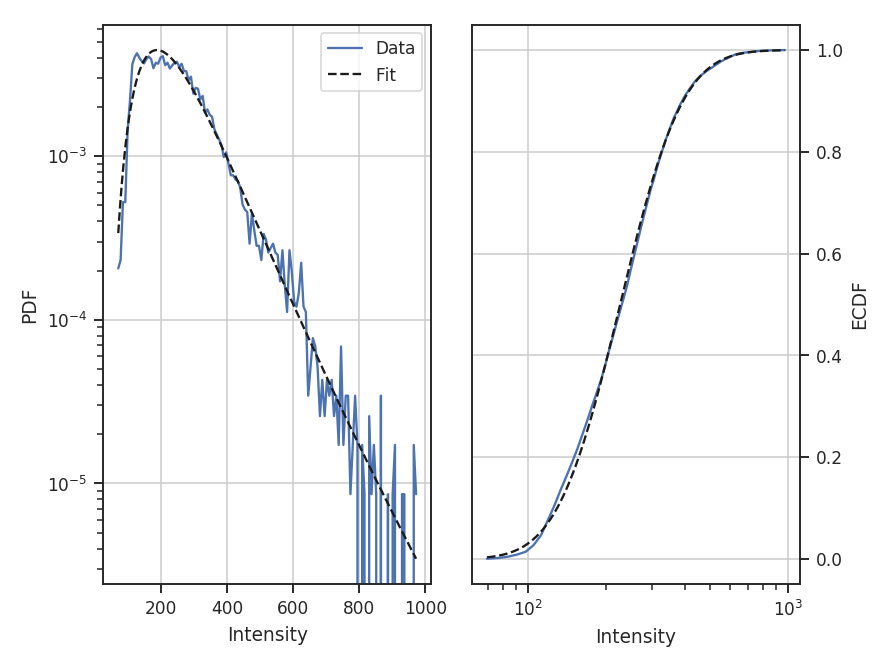

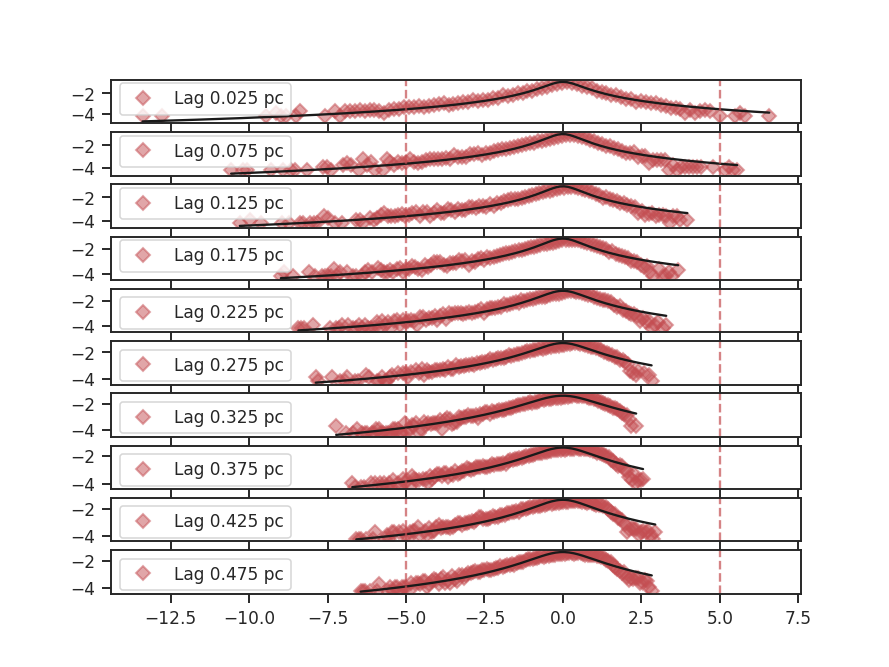

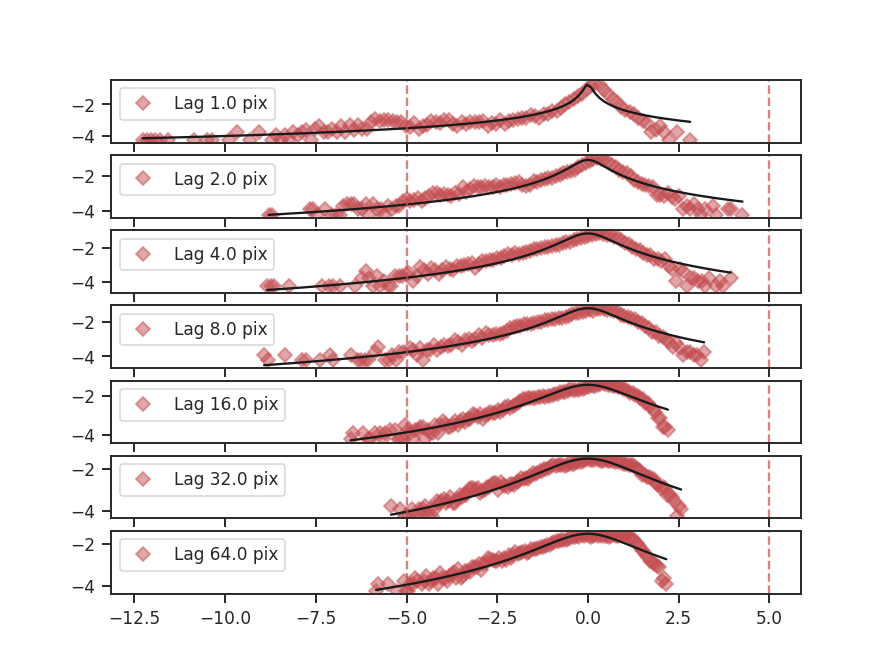

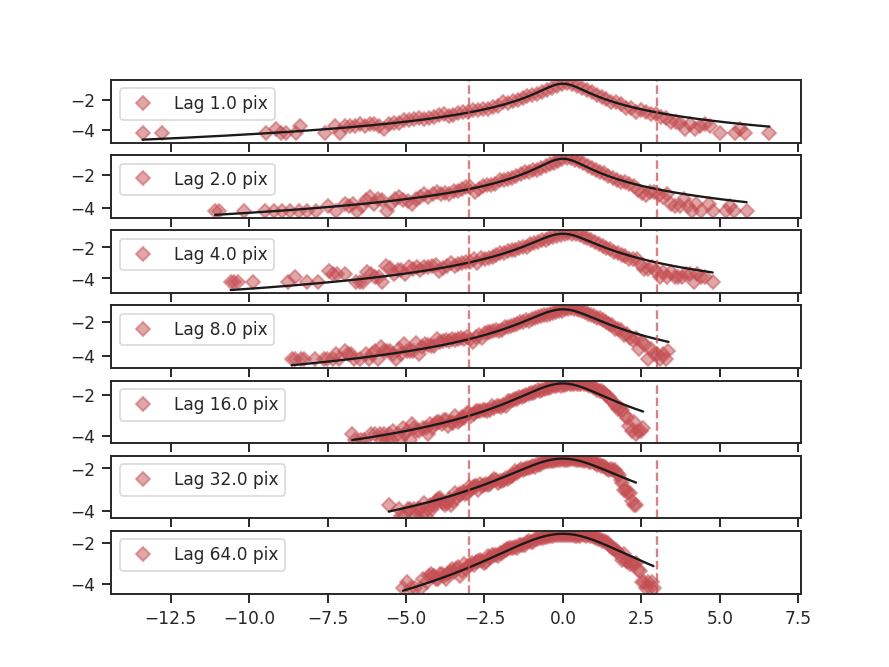

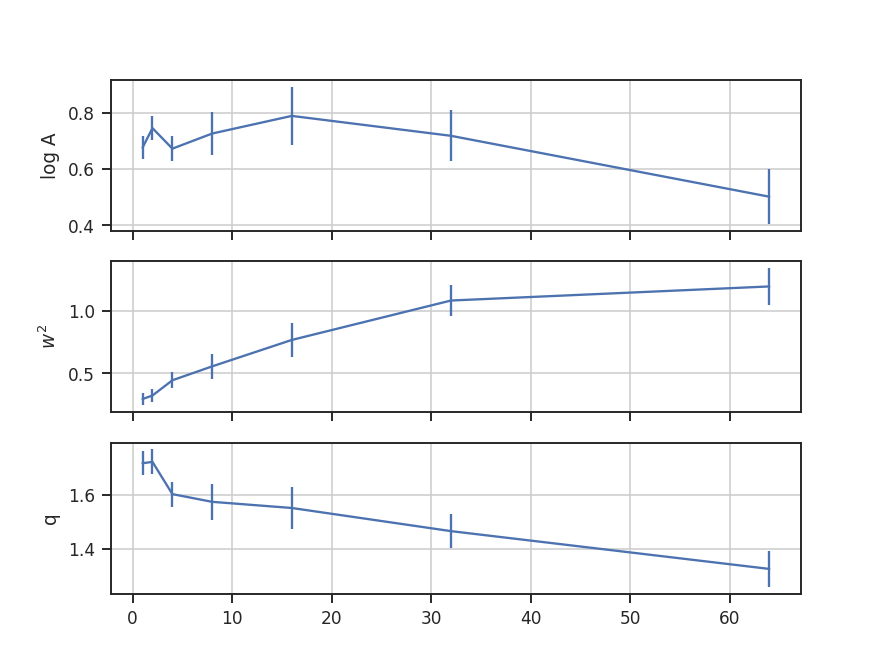

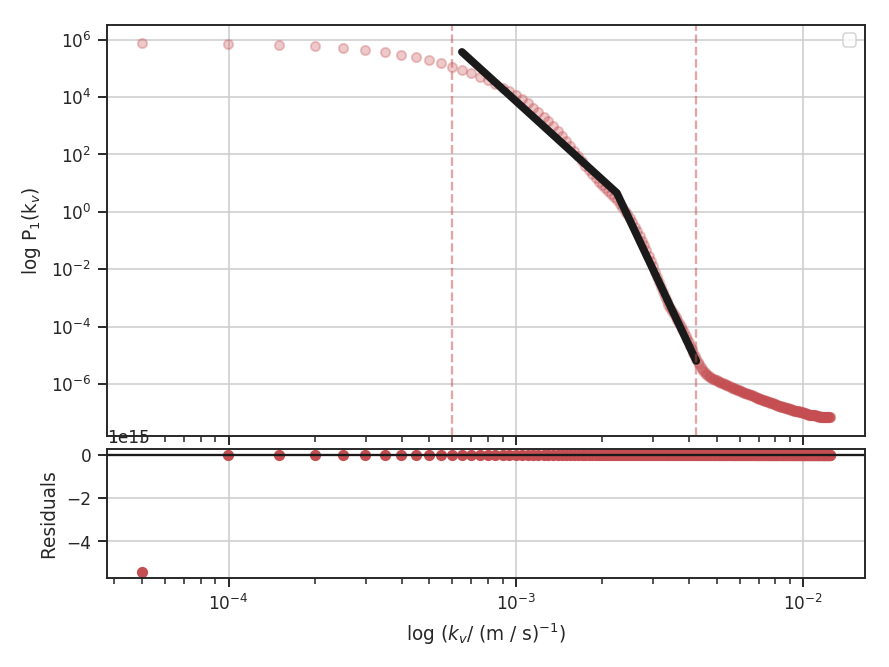

When an image contains NaNs, there are two important parameters for the convolution: preserve_nan and nan_treatment. Setting preserve_nan=True will set pixels that were originally a NaN to a NaN in the convolved image. This is useful for when the image has a border of NaNs. When the edges are not handled correctly, the delta-variance curve will have large spikes at small lag values.